Did Apple Stores save Apple?

How Apple became a retail powerhouse

Based in one of America's wealthiest counties, Tysons Corner Center brims with shoppers on a daily basis. But for the state of Virginia's largest shopping mall, the pre-dawn hours of Saturday 19 May, 2001 were unusually busy. "I have lived in the area for 17 years," said one visitor to the Center, "and I've never seen anything like it."

Some 500 people lined the precinct walkways, but this was no sales rush at Macy's or big-name book-signing at Barnes and Noble. The world's first Apple Store was about to open its doors to the public.

Inside, CEO Steve Jobs showed press around the white platforms and wall-length tables of iMacs and PowerBooks. Joe Wilcox was part of the group: "The store sports hardwood floors, high ceilings, bright lights and clean lines, similar to trendy clothing retailer Gap," he reported. "It's remarkably understated."

The comparison was apt – Gap's President and CEO, Mickey Drexler, had been on Apple's Board of Directors for two years. Even so, diving into a volatile retail space was far from what the board had had in mind.

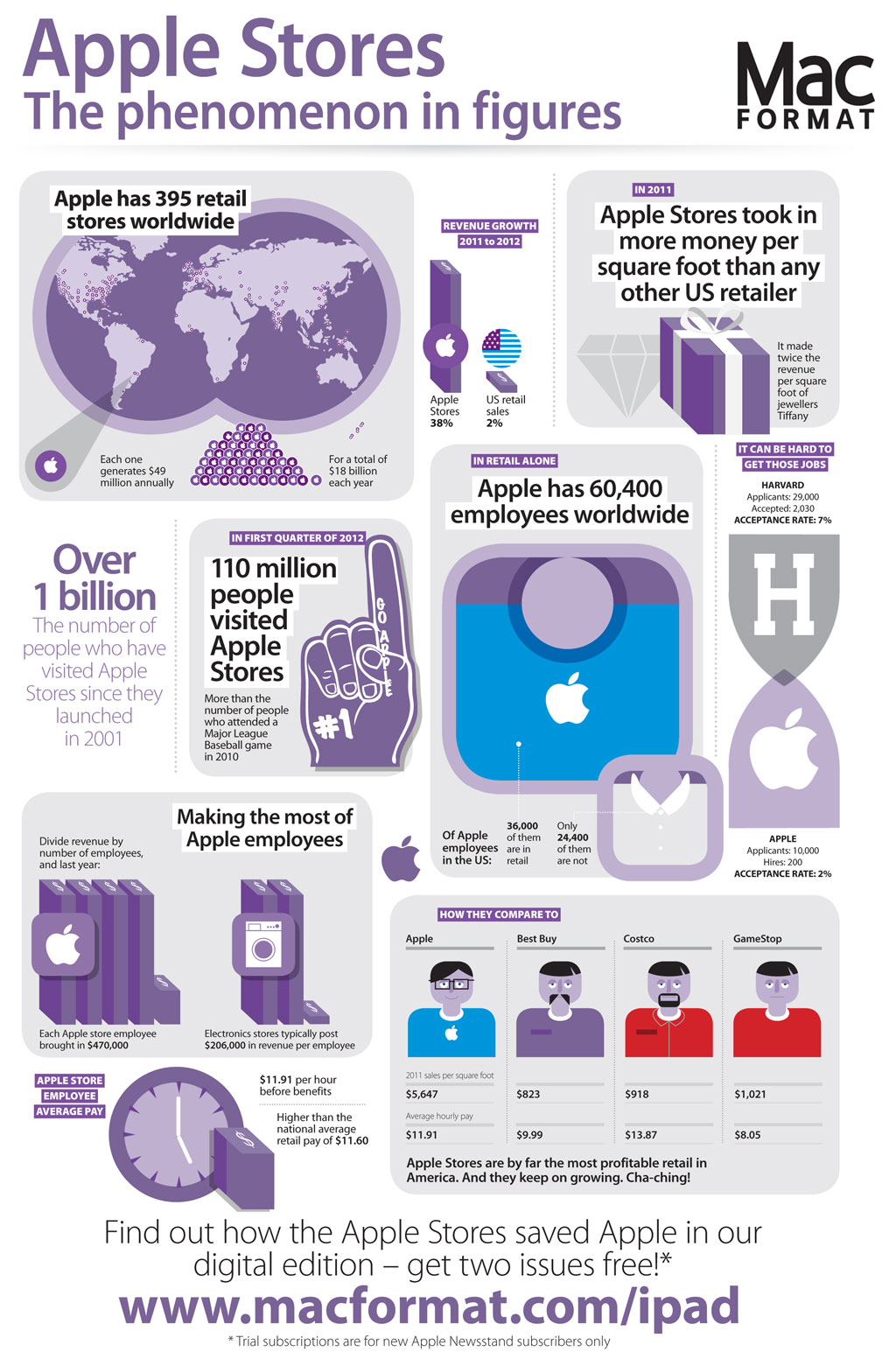

Check out MacFormat's amazing infographic on the rise of the Apple Store. Click the image for a bigger version.

Reality distortion

"The Apple store offers an amazing new way to buy a computer," announced Jobs to a rapt audience as he stood in front of the Genius Bar beneath a photo of John and Yoko. "Rather than just hear about megahertz and megabytes, customers can learn and experience the things they can actually do with a computer."

But the confident bravura on show that spring morning concealed the risky hand that Apple's board had allowed its CEO to play. For two years Apple's market share had hovered around a measly 2.8%. Slimming down a bloated product line had underlined the company's commitment quality, but for Jobs the problem had never been with the products per se; it was with big-chain retailers that hid away Macs in store corners and employed clerks who often knew as little about the products as the customers.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Jobs felt that Apple would never shake off its 'cult' image unless he could control the buying experience down to the moment of transaction. "Unless we could find ways to get our message to customers at the store, we were screwed."

His search for a retail executive to spearhead that message began in 1999. A series of secret interviews singled out Ron Johnson, the brains behind Target discount stores' highly successful branded merchandise line.

Johnson was the son of a General Mills executive, and had developed an interest in design after witnessing the way Italian company Alessi presented its pots and juicers as works of art at a Frankfurt housewares show. "It was like walking through a museum," he recalled. "They weren't there to make money; they were there to make great products."

The experience inspired him to take a gamble, and he hired the architect Michael Graves to create low-cost versions of his designer teakettles exclusively for Target. The move was shrewd – the line was such a hit that the retailer's image was transformed from vanilla discount outlet to a store that sold stylish but affordable products.

Jobs was so impressed by Johnson's belief in bringing elegant products to ordinary people that he asked him back for a second interview. This time though, the tone was casual. They took a walk to the local Stanford Shopping Mall. Retail philosophy and the conspicuous absence of technology stores dominated the discussion.

Johnson explained that computers were a major and infrequent purchase, so customers were prepared to travel to a less convenient location where the rent was cheaper. But Jobs eschewed expense; he wanted Apple stores in central malls where foot traffic was high, and where Microsoft-using passers-by could be easily coaxed inside.