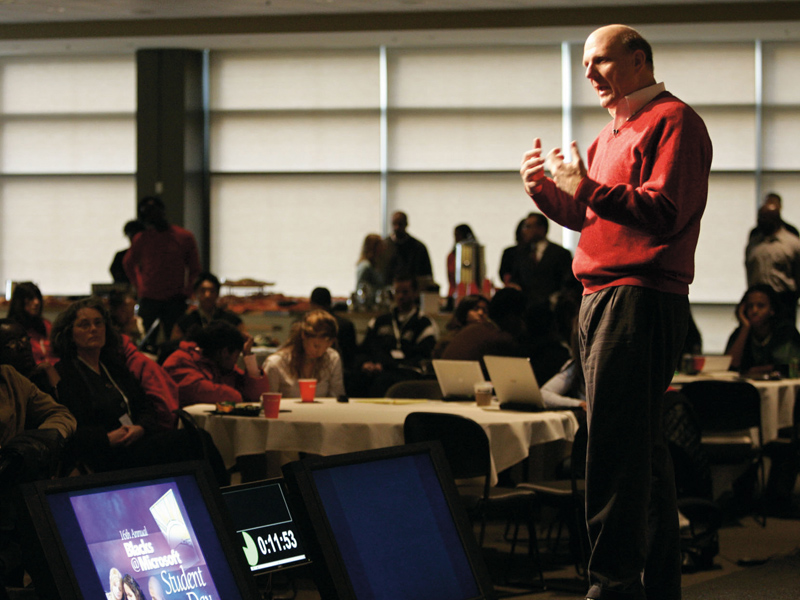

On the face of it, Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer and Gordon Brown don't have much in common.

One is a plain speaking, unpretentious, horny-handed son of toil who, after what seemed like an eternity, took over the top job from his best friend – only to find himself in charge of a crumbling empire with no clear direction, declining popularity and endless media coverage of his smoother, more stylish rival. The other is the Prime Minister.

The comparison isn't as bizarre as it might seem. With the departure of Bill Gates, Ballmer has inherited a Microsoft whose position looks much less secure than it did in the Gates era. Despite massive spending on search, Microsoft's market share is dwarfed by Google. It's outflanked in entertainment and mobile computing by Apple, it's losing browser market share to Firefox, and Silverlight is barely scratching Adobe's Flash.

The 'Wow' marketing campaign for Vista has been replaced with the more desperate 'if you try it, you might not hate it' Mojave campaign, and mini-PCs – one of the few PC sectors that hasn't stagnated – are sticking with Windows XP. Even Office, Microsoft's cash cow, is under attack from free and open source rivals.

So has Ballmer inherited a poisoned chalice? Has Microsoft lost it? And if it has, can it find it again?

Cracks appearing

Microsoft is still making enormous sums of money, but cracks are appearing in its $16billion Windows business. The death of XP has been postponed several times – the current rash of ultra-small, ultra-cheap laptops don't have the horsepower to run Vista – and while Microsoft claims to have sold 180 million Vista licences, many of those licences are for machines running XP.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

As Jane Bradburn of HP Australia told reporters in July, "From 30 June, we have no longer been able to ship a PC with an XP licence. However, what we have been able to do [is] to ship PCs with a Vista business licence but with XP pre- loaded. That is still the majority of business PCs we are selling today."

There's no compelling reason for users to upgrade: Vista requires more powerful hardware than XP, and it's been plagued by driver problems and incompatibilities. As a result, it's faced an avalanche of bad publicity – some of it deservedly so, as users found that their devices didn't work.

The bad publicity isn't helping enterprise adoption. According to Forrester analyst Ben Gray, "Desktop operations professionals tell Forrester that they see the value in standardising on Vista, but many are having a hard time convincing their CIOs that the move isn't a risky bet, given the mixed reaction it's received in the press and the speculation surrounding what to expect after Vista." Forrester reports that 8.8 per cent of enterprise customers have migrated to Vista; 87 per cent are still running XP.

The 'mixed reaction' has been a gift for Apple, whose 'Mac vs PC' campaign mocked Microsoft ruthlessly. The ads worked: according to BMO Capital Markets analyst Keith Bachman, "More than 50 per cent of customers buying Macs in Apple stores are first time buyers."

Fixing Vista

Microsoft doesn't normally acknowledge its competitors, but in July, Steve Ballmer used the A-word in a company-wide memo. "In the competition between PCs and Macs, we outsell Apple 30 to one," he wrote. "But there is no doubt that Apple is thriving."

That's something of an understatement. Apple is now the third biggest computer manufacturer in the US and the sixth biggest worldwide, with a US market share of 8.5 per cent – compared to two per cent in 1996. While the PC market grew 4.2 per cent in the last year, Mac sales are up by 38 per cent. It has 17.2 per cent of the UK educational PC market and its iPhone came from nowhere to grab 27 per cent of the American smartphone market.