How Syndicate went from clever AI exercise to murderous cyborg mayhem

Direct from the Bullfrog's mouth

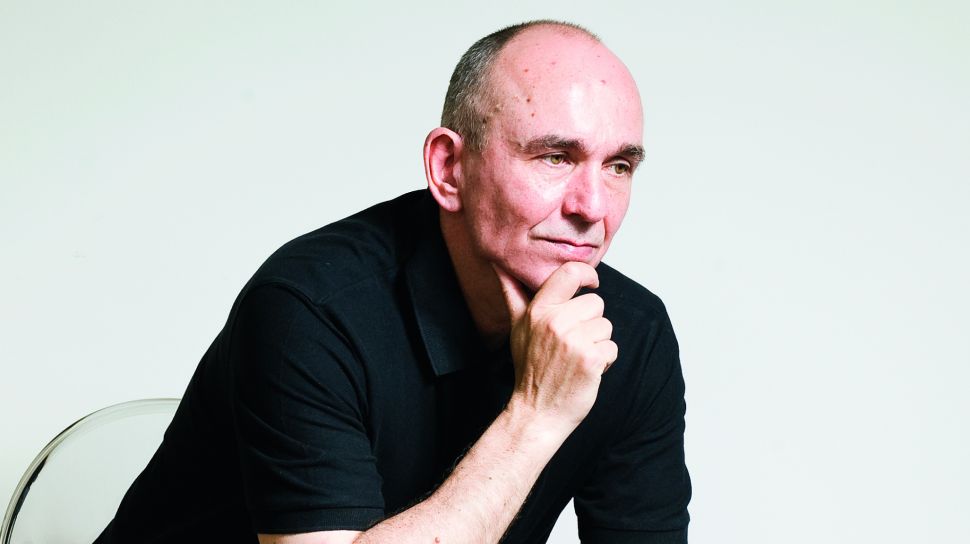

Peter Molyneux, once a lonely solo programmer, brought together a wealth of talent to create the Bullfrog outfit responsible for Syndicate, but what's the secret to picking out a top games team? We find out by taking a look back at Amiga Power's original interview with Molyneux's team from 1992.

Peter Molyneux, once a lonely solo programmer, brought together a wealth of talent to create the Bullfrog outfit responsible for Syndicate, but what's the secret to picking out a top games team? We find out

- Company: Bullfrog

- Location: Leafy green Surrey

- Typical game: Strategy god-game

- Most notable games: Populous, Powermonger, Flood

- Current project: Syndicate, an action/strategy game set in cyberpunk future in which you control a team of four cyborgs. The idea of the game is to take over the entire globe by completing 50 missions ranging from assassinations to escort duties.

- Time in development: Three years

- Key personnel: Peter Molyneux (co-founder of Bullfrog), Sean Cooper (head programmer), Paul McGlocclen (head of graphics), Mike Diskett (head of conversions).

There are few software developers as influential as Peter Molyneux's Bullfrog outfit. Ever since Bullfrog released its first god-game, Populous, it has been creating innovative titles with a long shelf life, including Powermonger and Flood. And for the last three years the team has been working on a cyberpunk game called Syndicate.

Like many developers, Bullfrog has changed from a small team of general programmers to a large group of specialists. Populous was programmed entirely by Molyneux, and head programmer Sean Cooper masterminded Flood, Bullfrog's only platform game to date. The company is now made up of a large team of graphics artists, sound engineers, conversion specialists, play-testers and programmers.

"I'd love Bullfrog to be like it was when we did Populous, with eight of us all together in the same room," says Molyneux, "but you can't stay that way. You'd die.

"It's sad that you have to have this management structure, but it's either that or you get gobbled up by a big company. The dream of Bullfrog is that everybody is employed for their creativity rather than their particular skill."

Changing role

Molyneux's role has changed over the years from lone programmer to producer. He now co-ordinates all the resources of the team, making sure that the artists and programmers are doing their bit. To keep track on how a game is developing, Bullfrog has 'Technical Design Reviews'. These pinpoint any problems with the game and what the current configuration of the memory is.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Bullfrog also uses play-testers as it develops games. Two schoolkids come into the office every week to play and rate the game under production.

Molyneux explains: "What we do first is show them a crappy game. Not one of ours, but someone else's! Then we get the to mark it and ask them to justify the marks they give it. So hopefully, in the end you get marks that are representative of how they feel. The play-testers are the ones that really balance the game."

Bullfrog's latest release, Syndicate, starts off pleasantly with some undemanding introductory missions, and builds to a bloody climax on the last mission, the Atlantic Accelerator. It takes about two weeks of solid play to complete the game, taking in all 50 missions. Originally there were going to be 150 missions, but time ran out.

Complex character

The original idea for the game came out of the team's experiences programming Populous and Powermonger. Molyneux says the first idea was to get complex actions into a character, but still present them in a simple way, although he explains: "The actual end result was completely different!"

Syndicate started out as an exercise in artificial intelligence. The programmers created a system of three bars which enable you to decide how perceptive or intelligent your team of four cyborgs are. However, as they developed the idea, the use of bars changed.

Molyneux explains how the emphasis of the game changed in development: "We realised that it was actually far more fun to just take your agents into the city and blow everything up. Now the bars are still there, but the actual strategy part of the game has been toned down."

Another problem in the game's development was designing the nice 'n' easy icon-based control panel. "It was the hardest thing to design," admits Molyneux.

"To start with we had icons with stuff like pick up weapon, shoot weapon, drop weapon… there were masses of different ones. Then we realized there was little point in having all those icons - if you click on a weapon then the cyborg should pick it up, it should be obvious. You're not clicking on it to spray it gold; you want to pick it up (many a true word spoken in irony).

"So now it looks simple, you've just got the scanner, four icons and the weapons icons." Easy to use… we like that.

The team speak

Molyneux had a huge team of specialists working on Syndicate: Sean Cooper, coding: Paul McClocclen and Chris Hill, graphics: Russell Shaw, sound Alex Travers, missions and play-testing; and Michael Diskett, who is in control of conversions.

Sean started work on Syndicate three years ago, so it's been a long time in development. The game is programmed on a PC set-up with a central core which calls on a library of modules. This meant that Sean could concentrate on the actual game, making the process of programming quicker and more compact.

Sean explains how the game was put together: "It started off as an action game in pseudo isometric 2D because the isometric view appealed to me. We used to have really big sprites for the cyborgs, then we had small ones, and finally we plumped for the medium height ones which are in the finished game."

But the programmer's real nightmare are bugs. "The worst kind is when you haven't touched a piece of code for six months and it goes wrong," says Sean. "That means you've got to go back to it and work your way through it, trying to remember what you did with that piece of code. We were lucky with Syndicate - it only took two weeks from being a Beta game to being a final version."