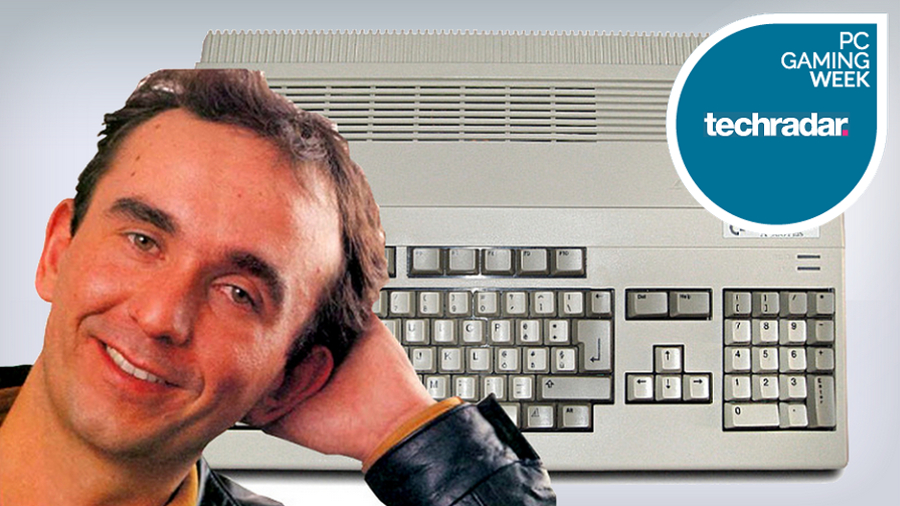

What was Peter Molyneux's magic formula for addictive Amiga games?

Amiga Power talked Bullfrog's beginnings with the God of God sims in 1991

Amiga Power went down to the pub with Peter Molyneux and his Bullfrog colleagues in 1991 to talk Amiga games — including Populous II, Powermonger and 'Bob', which turned out to be the wildly successful Syndicate that was released in 1993.

Ask someone to name a programming team and they'll invariably come up with the Bitmaps. Ask them to come up with a second famous team though and the answers will vary a bit – some (those with long memories) may mention Jez San's Argonaut mob, others might plump for The Assembly Line or Core.

Chances are, though, most will pick out Bullfrog – they may not wear shades and stare meaningfully into the middle-distance, but they have developed a distinctive, recognisable style (this 3D isometric for-want-of-a-better-word 'God-sim' stuff), they are consistently interesting in what they do and (most importantly) they did, after all, develop Populous.

Ah, Populous. Without doubt one of the most distinctive, original games ever seen on the Amiga (or indeed elsewhere), Populous has become something of an international phenomena. It's sold a good 750,000 (750,000!) units worldwide ("Guess how many different machines you can play it on now?" Peter Molyneux asks, "Fifteen!"), and is still constantly referred to as 'One of the Greatest Games Ever Written'.

Who are Bullfrog?

It's the sort of thing that becomes an obsessive experience with people. (Indeed, ask Peter what games he's been playing recently and he comes over all sheepish – "I still play Populous quite a lot," he eventually admits).

Here's another question for Peter Molyneux – how would you describe Bullfrog? After a bit of rigmarole ("I'll only answer that if you'll tell me how you'd describe yourself" etc) he eventually comes out with some variation on his 'slow, disorganised, but keen' line. That being said, for a team of only seven or eight people they've got a lot of things on the boil.

There's Creation, the genetic engineering-based project, there's the as-yet-not-properly-named 'Bob' ("I think it has the potential to become the best thing Bullfrog has ever produced," he told us last issue), there's the Powermonger data disk, there's another further away and more mysterious secret project and then, of course, there's Populous II.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

"Of all the programs we've done, this is the one I really wanted to do," says Peter. "It's because I like playing Populous so much, but I keep seeing ways in which we should change it." Certainly, if ever a program was 'long awaited', this is it.

In fact, it's the chance to see it at an early(ish) stage that gets me and photographer Stuart into a (painfully slow) Fiesta hire car with a boot-load of lighting equipment and an illegible set of instructions for a day-trip to Guildford. In particular, for a day-trip to a typically programmer-chic (i.e. ratty and run down) series of offices above a hi-fi shop in the centre of town. "It's a stupid place to be," says Peter, "there's no need for us being in the city centre like this. It just sort of happened."

Back in business

Bullfrog's offices – the place is signposted 'Taurus', the name of the old business software company the outfit was born out of – occupy a number of floors built around a rickety staircase.

The bulk of the programming seems to be done in the one at the top, a room shared with a tankful of baby piranha fish ("we catch them tiddlers from the river to feed them on – the thing is, they'll only eat food that's moving") and a thankfully separate tank full of Oscars (another wimpier sort of fish) which'll gladly gum your finger to death. So it's here, in these slightly unlikely surrounds, that great games are made, eh?

"Well, sort of. The easiest and hardest part of it all is coming up with the Good Idea to start with. That can be done anywhere – usually we go down the pub, or for a meal, and just bounce ideas around until one sticks. In fact, I've got tapes of the original conversations we had about Populous – if you listen to them there'll be one point where you can say, 'Yes, there's where the idea came from. That was the moment we thought of the game'."

Big in Japan

We've had some Japanese magazines in the office lately, I tell Peter. LOGiN's the famous one, but there are lots of others and they're all about 400 pages long and totally unintelligible – apart from the Populous ad with its little Bullfrog logo on the back cover, that is. When you think that all those people in Japan know who Bullfrog are, or certainly know your games, you get to a state where you're expecting something of a more, well, impressive operation than you've got here.

"Yes, I know what you mean," he replies. "We had a few journalists from LOGiN here the other day actually. I don't know what they expected, or what they thought of what they found. They took us outside and made us all climb up a tree to have our pictures taken. Not like you lot at all."

He's referring to the fact that Stuart's currently struggling up the narrow stairs with armfuls of lights and rolls of white paper to set up for our photo shoot later. While he's doing that we take a brief look at some games – very impressive, the lot of them, though going in all directions that make Flood look like even more of an anomaly ("We did Flood purely to prove we could do something like a platform game," says Peter.

"We didn't want to become known just as the 3D isometric God-sim people") before breaking for lunch down the local pub. It's a nice one, with seats going down towards the river, so we sit outside and talk games and magazines.

Righting wrongs

We try and think of games that would qualify as the 'most overrated of all time,' and ones that 'should have been great, but weren't'. Peter talks about the importance of graphic designers to games ("they have at least as much say in the look and feel of them as the programmers, but they're hardly ever covered in magazines") and we try to come up with new ideas for things that we should try and do in Amiga Power. It's here that the idea for our 'Win a job at Bullfrog' competition came from, for instance.

"When we were doing Populous the first journalist to see the game came down – he was from Ace magazine, back in the days when it was with you guys at Future – and I was really worried. What would he think of it? Were we totally barking up the wrong tree, or not? It's so hard to know when you're that close to a project. Thankfully he liked it – this real megastar, big name journalist liked it! In fact, when we came back to the office all he'd do was play it some more. I don't think he realised how much that meant to me."

It's interesting to know how much outside opinions can mean when you're developing a product, but I can only laugh when I realise this 'big megastar journalist' was in fact cuddly old Bob Wade, currently editor of our sister magazine Amiga Shopper, occupying the office just next to the Amiga Power one.

As we leave he tells me he'd taken the guys from LOGiN down here too. "They asked where our ideas came from, so we bought them a pint of Burtons Bitter and told them here, this is where – this drink has special creativity-expanding properties. I'm not sure if they swallowed it, ha ha, but they certainly drank up their pints."

Current page: Introduction and inside Bullfrog's offices

Next Page The importance of playtesting