Cloud computing explained

The cloud; a modern-day expression of ultimate globalisation, or just a slew of servers somewhere in Arizona? At the time of writing the term 'cloud' typed into TechRadar's search engine produced 1,293 results in the news section alone; the cloud makes headlines, and it sells products.

Why? It's exactly the cloud-powered desire for 'anything anywhere anytime' that has led to the creation of 4G and the frankly silly name of UK service Everything Everywhere.

The language of the cloud may be unequivocal, but don't expect that to last long; within a few years you'll put cloud costs next to other utilities such as water, gas and electric. The cloud catches our imagination, and is fast becoming the stuff of life itself. But what exactly is it?

What is 'the cloud'?

"The cloud is a collection of interconnected IT services and infrastructures that are accessible via a network," says Dr M Rajarajan, a reader in information security at City University London.

From a user's point of view, anything that backs up and syncs data that's accessible on multiple devices can be said to be a cloud service.

Familiar products that use the cloud include Google Drive, iPlayer, Apple's iCloud, Amazon's Cloud Drive, its new Cloud Player and its Kindle Cloud Reader and apps, Spotify, and Sony's next PlayStation. Plus there's a whole host of online storage and back-up services such as SugarSync, SkyDrive and Dropbox.

Although we're most interested in what it can do for all of us, even these brands offer cloud services to private companies that enable them to slim down both their own IT operations and desk space. After all, if everything is stored remotely on the cloud, who needs an office?

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Where is the cloud?

The cloud is real, and nothing like a cloud. It lives primarily in wealthy, cooler parts of the world, far away from floodplains and even flight-paths.

Stored in office blocks or warehouses, the world's major data storage centres are primarily in the US and Europe, though there's growth in Asia and Australia.

"The world's largest technology companies tend to dominate the sector, but most are very secretive about the number and location of facilities they have, because they don't want to give away competitive advantages," says Edward Jones, CEO of PMB Holdings, which operates the MK DataVault.

"Google, for example, is known to have at least a dozen major facilities in America, but is believed to have many more, as well as an increasing number of locations in Europe and Asia."

What we do know is that around 90% of Google's data is stored in the US and Europe (in Finland, the Netherlands, Belgium and Dublin), though it also has warehouses in Russia, South America and Asia (Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan).

Storing your iTunes collection on Apple's iCloud means renting space at its data centres in Oregon, North Carolina or California, while status updates on Facebook reside in, strangely, almost exactly those same places, as well as Virginia and, soon, Sweden.

Microsoft puts its data in its US heartland (its facility in Washington is larger than 10 football fields), though it does have one data centre in Dublin, while the exceptions to Amazon's US-centric strategy include Dublin, Japan and Brazil.

Tweets, meanwhile live on Twitter's servers in Sacramento, California and Atlanta, Georgia.

"Although the locations of 'cloud islands' are often clearly identified in terms of where the underlying services or data centres are located, these locations may be compounded across national boundaries," says Dr Rajarajan, who goes on to suggest that since the cloud islands are interconnected it can be claimed that the cloud can be potentially everywhere. A bit like the internet, then.

How does the cloud work?

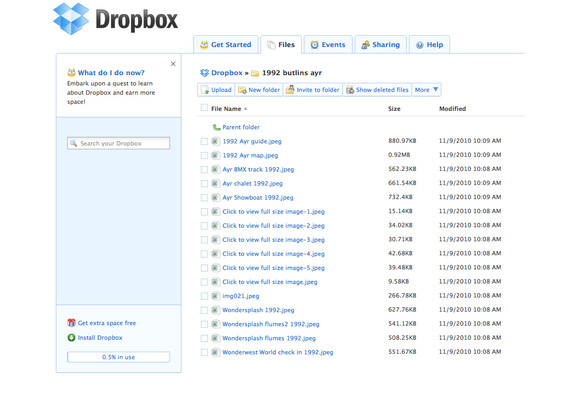

Take store 'n' sync service Dropbox as an example. Its software is installed on 250 million devices, with its 50 million users saving one billion files every couple of days on its cloud servers.

All of that data is encrypted and kept on Amazon's Simple Storage Service in multiple data centres across the US. The idea is that you work away on your PC at home normally, but every file or folder you link to Dropbox is automatically - as in, almost constantly - backed up to a Dropbox server.

You can access your Dropbox account from any web-connected computer, but in terms of remote working it goes even further; load Dropbox onto your netbook, tablet or smartphone and you can access the latest version of any given file. Make changes to a document and that version now becomes the version accessible on your desktop PC.

It takes a while to get used to it, but there are fail-safes; conflicting copies of files from different machines are clearly labelled (if, for example, you work on a document on two different devices, one of which isn't connected to the web, so unable to sync).

Dropbox keeps snapshots of every file change over the last 30 days, so can retrospectively restore files, too.

The key advantage of this kind of service is that it integrates totally into your devices, and is pretty much invisible. That is why we love the cloud - and why Dropbox-style services of some sort are now touted by every web brand you can think of.

What is cloud computing?

"The cloud goes beyond simple storage," says Greg Mason, a partner at the Forensic Risk Alliance. "Cloud computing offers both data hosting and applications, so consumers are free to access this from anywhere."

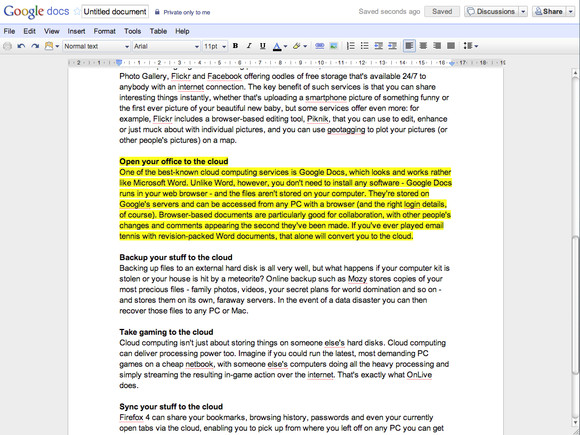

Nice in theory - no need to buy an HDD or even software - but despite the efforts of Samsung's Google Drive-powered Chromebooks, cloud computing proper hasn't yet caught on.

The software and technology that enables us all to work solely through a web browser is here, but since an 'always on' web connection isn't guaranteed, the Chromebook idea only really works if you're stationary. For now, that defeats the object.

But the era of corporate offices spending big on licenses to install software on multiple computers is drawing to a close, with some predicting that cloud computing will herald what's rather hastily being called Work 3.0. Yuck.

Is the cloud clean?

It could be, but it isn't - yet. In the long run, as well as saving time and money, some think that the cloud will have enormous environmental benefits. "Cloud computing brings the potential to outsource and eliminate almost every non-mission-critical complexity in an IT infrastructure," says Chris Gabriel, VP of Solutions Management, at IT supplier Logicalis Group.

Gone from even relatively small offices will be control rooms housing banks of servers, in need of cooling. And though the cloud does mean huge data centres somewhere on the planet, we're talking massive economies of scale.

Eventual environmental bliss? Perhaps, but not yet. Greenpeace has been most vociferous about dirty data, issuing its 'How Clean Is Your Cloud?' report in April that claims cloud computing is "driving significant new demand for dirty energy like coal and nuclear power".

"When people around the world share their music or photos on the cloud, they want to know that the cloud is powered by clean, safe energy," said Gary Cook, Greenpeace International senior policy analyst. "Yet highly innovative and profitable companies like Apple, Amazon, and Microsoft are building data centres powered by coal and acting like their customers won't know or won't care. They're wrong."

Phrases such as "visible from space", "use as much electricity as 250,000 homes" and "triple by 2020" were used by Greenpeace to describe some data centres.

However, the report did praise Google, Yahoo and, in particular, Facebook for moving towards renewable energy. Apple's iCloud was criticised for its new data centre in Maiden, North Carolina, which will primarily use coal power, according to Greenpeace.

How secure is the cloud from fraud?

Your data is someone else's hands. That's the cloud in a nutshell, and it creates a possibility that our personal and financial information is vulnerable to fraud. But don't get paranoid.

"Most individuals will store information on the cloud for sharing purposes or backing up data," says Mason, suggesting that most of our stored data is not as critical or sensitive as corporate data. He's probably right, though he does issue a word of caution, telling us: "Individuals should still be sensitive to the nature of the data they are storing in the cloud."

For example, your holiday pictures and music collection are, frankly, of no interest to most of your family and friends, let alone the world's hackers. Upload your 'passwords to remember' file alongside a collection of scanned-in maps of the location of sunken Spanish galleons from the 15th century and you might have a problem.

Besides, cyber-space isn't safe - everybody knows that. "The cloud remains deeply associated with off-the-shelf solutions from the likes of Amazon and Google," says Gabriel, "and servers at these organisations are indeed targets for cyber criminals."

It was quickly rectified, but during July, Russian hacker Alexey Borodin changed the DNS settings on Apple's In-App Purchase Programme, which allowed Mac users to avoid the payment process and steal in-app content.

"It was not Apple's first DNS hacking incident, and is unlikely to be its last," says Gabriel. "The difficult nature of detecting DNS attacks means that they could be likely cyber-crime choices for terrorists."

Are the cloud's data centres targets for 'real' terrorists?

Oh yes. In 2007 Scotland Yard uncovered - and prevented - a plot by Al Qaeda members to infiltrate and destroy a major colocation data centre owned by Telehouse Europe, considered one of the main hubs for the internet in the UK at the time.

"That made it clear that data centres are indeed on the radar as a target for terrorism," says Jones. "The chances of an attack may seem remote, but they should still be accounted for, and in any case all data centres should have strong security and emergency backup measures in place as standard."

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),