Next-gen Oculus Rift headsets could focus on holographic displays

Chasing the Holy Grail of VR - depth of field

VR is incredible. Anyone who has spent any time with either of the top-of-the-range headsets - the Oculus Rift or HTC Vive - will know that VR is an experience that is almost impossible to explain, even to those that have tried the more accessible Gear VR.

That said, it isn’t perfect. One of the main things that feels unnatural is the fact that everything is in focus the entire time. It doesn’t feel too jarring to start with, it’s more that you just have a feeling that something isn’t right. Your brain knows that what it’s looking at isn’t real. It can’t be.

In the real world, when you look at an object, your eyes automatically focus to that point and the rest of the world goes out of focus. The problem with VR is that no matter where you are looking in the VR world, you’re only ever actually looking at the screen, which is the same distance away.

This leads to a problem catchily referred to as vergence-accommodation conflict (VAC), that according to Oculus: “has been attributed as a source of visual discomfort: viewers report eye strain, blurred vision, and headaches with prolonged viewing.”

And there was us thinking it was just having a screen an inch from your face that was causing that.

- Watch the two flagship VR headsets square off in HTC Vive vs Oculus Rift

What am I looking at?

It turns out that Oculus has been working on a solution for this problem, detailing to TechRadar plans to implement a ‘focal surface display’. For an explanation about how this works, check out the video made by Oculus below.

In the video, there are a few different methods for creating focal length; quickly displaying 'slides' of the different distances, using holography, and using focal surface display, where an image is seen through an element that manipulates the focal depth of subjects of the image.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

One of the things that is still unclear from this video is how the screen decides which section of the screen is in focus and at what time. At this point the focal depth is being decided by a computer rather than by the need of a user, but there are significant mentions of the placement of the user’s gaze in the paper that Oculus published on focal surface display, hinting towards the use of eye-tracking technology.

This would seem to be verified by a statement made by Douglas Lanman, one of the researchers working on the technology, during a Q&A posted to Oculus' blog site: “I do see an emerging trend in VR displays: increasing use of adaptive optical elements like phase-only SLMs, often in concert with eye tracking technologies”.

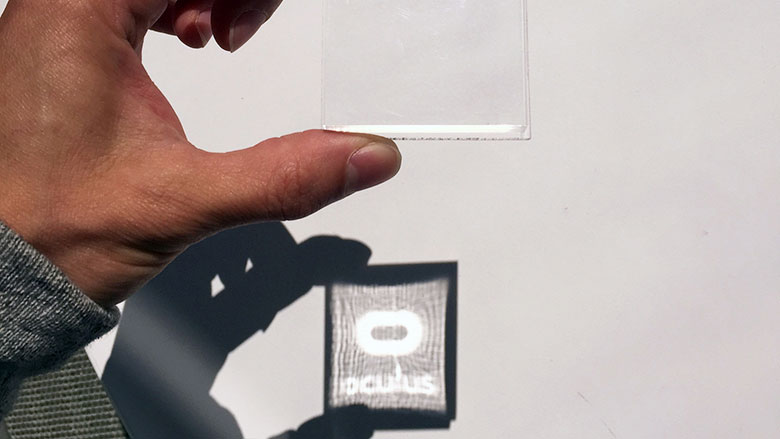

An SLM is a Spatial Light Modulator, and is effectively the element that sits between the screen and the lens, which “bend[s] the focus as a sort of programmable lens element”. To get a visual reference of how a lens can bend light, check out the awesome picture from the Oculus lab below.

According to Lanman, we are only going to see more of these kinds of focusing elements in VR headsets in the future:

“After all, if the goal is to deliver more accurate focus in VR headsets, adopting digital focusing elements is an obvious path forward, but the use of adaptive optical elements could range from something as simple as a digital autofocus system (a so-called “varifocal” HMD) all the way through to near-eye holographic displays.”

Future gazing

Near-eye holographic displays sound awesome, and while Lanman seems to be intentionally vague about what this could be (he starts his statement with “I can't comment on future products from Oculus”) it is clearly a field he is excited about:

“I am very interested to see what lies between Focal Surface Displays and holography... Due to the common use of an SLM, holography and Focal Surface Displays inherit somewhat related benefits and limitations.

"Holographic display is a well-established principle, so its benefits and limitations are largely known (but reducing it to practice is by no means simple). With Focal Surfaces Displays it’s not entirely clear yet what the best way to drive and operate these displays is. I can't wait to learn how other researchers can carry forward and evolve this concept. ”

If this is all sounding very sci-fi, that is intentional. Another of the researchers said: “My personal motto for my own research is that if I’m not working on something that would count as a Secret Project in Sid Meier’s Alpha Centauri—i.e., something that would’ve been magic sci-fi future technology in 1998—then I’m not trying hard enough.”

- Check out our Oculus Rift review

Andrew London is a writer at Velocity Partners. Prior to Velocity Partners, he was a staff writer at Future plc.