How wearables are changing sports and winning championships

Wearables aren't the future of sports - they're already dominating

Wearables are taking over sports

Every professional sporting event relies on the premise of fair play: no one player or team is allowed better equipment or technology that gives them an unfair advantage over their opponent. So when evidence arises that the integrity of the game might have been compromised - the BALCO steroids scandal, Deflategate, Spygate - widespread outrage and judicial hearings quickly follow.

Health-monitoring wearables and virtual reality devices are still a nascent, evolving industry, and as a result, these devices' impact on sports hasn't received much public attention. Yet many college and professional sporting teams have adopted various technologies to great success, even resulting in championships for some. Whether wearable tech merely correlates with rich, successful franchises or actually improves the odds of victory remains to be seen. Regardless, wearables have the chance to provide detailed and accurate information to coaches to prevent major player injuries, improve technique and conditioning, and analyze the competition.

Does this mean wearables could emerge as the latest performance-enhancing controversy in the sporting world? Or is the use of these powerful technologies fair play and the result of smart pre-game planning?

Let's take a look at five professional and amateur leagues that have seen the most widespread adoption of wearables, with surprising and even potentially unfair success.

Basketball

During the Golden State Warriors' historic run to the NBA championship last March, coach Steve Kerr decided to rest uninjured phenoms Stephen Curry and Klay Thompson before a key game in Denver, leading to an uncontested loss. Fans were furious and pundits perplexed, but Kerr had no choice: the athletes' wearables had warned him his stars were exhausted. A reenergized Curry and company moved on to win the Finals.

In-between games, Warriors players wore Catapult monitoring devices under their jerseys during workouts, and Oracle Arena was outfitted with SportVU cameras that track players' every movement, according to Grantland. Combining the internal and external data from these devices allowed coaches to track everything from speed and acceleration over time to force generated from each leg during a jump - an unbalanced jump shot may warn trainers of a leg injury before even the player becomes aware there's a problem.

Did the coaches' meticulous attention to wearable data keep the Warriors healthy all year when every other playoff team lost at least one star player? Possibly, although other NBA teams have adopted monitoring devices, not just the Warriors. Still, the Catapult-SportVU combination has proven so effective that teams now want to use the tech during games, too, to fully protect players from harm, even if players might want to judge for themselves if their bodies are ready to play.

Image Source: CBS Sports

Soccer

Two minutes before stoppage time in the 2014 FIFA World Cup Finals against Argentina, German Coach Joachim Löw knew his team needed a burst of energy off the bench. He had two choices of substitutes, each player's abilities represented by the data in the green rectangle above. He unsurprisingly chose the player on the right: midfielder Mario Goetze, who went on to score the game winning goal of the championship.

With football players averaging between seven and 9.5 miles of nonstop movement per game, as reported by Gizmodo, managers need to be keenly aware of their players' peak endurance levels and explosiveness when choosing when and whom to substitute. Where old-school coaches must rely on situational strategy and gut instinct, Germany's coach used hard data from Adidas' micoach technology to track players' health and endurance and make key roster decisions before and during matches, as noted by Geekwire.

Other professional teams are embracing wearable tech to an almost religious degree. Wareable reports that Southampton FC doesn't just measure heart rate and energy levels using STATSports GPS trackers, but also tracks players' sleeping habits and mood swings with Fatigue Science ReadiBands and logs bio-mechanical data with "underwater cameras" in the team's bio-therapy pools. In the club's own words, they focus on "breed[ing]" their young talent, investing in expensive technology instead of expensive player contracts.

Meanwhile, MLS team Seattle Sounders FC coincidentally uses the same Catapult harness technology as the Warriors, and have used players' health data to improve endurance, contributing to the team scoring 33% of their goals in the final 15 minutes of play.

Are wearables making these clubs better, or are wearable companies claiming the successes of objectively better and wealthier clubs? Would Löw have selected Goetze anyway thanks to his instincts as an experienced coach? And do the Sounders score more in later minutes simply because their players are "clutch" and play with greater desperation in the final minutes? Or is hard data finally solving the intangibles of sporting success?

Football

When Stanford University Coaching Assistant Derek Belch visited the university's Virtual Human Interaction Lab (VHIL) in 2014, he envisioned how the lab's cutting-edge VR technology could be used to train his athletes - specifically, his quarterbacks.

Most football position players can train in small groups at their own pace, but quarterbacks need 22 players working at peak energy for hours to truly prepare for games. But with VR practice reps using Oculus DK2s, quarterbacks can train independently against predetermined plays - four-man rush, zone coverage, unblocked rushers - until they are fully prepared for their opponent's playbook.

Belch founded STriVR Labs based on this premise, with immediate results for his team. After QB Kevin Hogan joined STriVR's pilot program, Stanford's scoring average improved by 14 points per game, while its red zone efficiency leapt from 50% to 100%, according to Fox Sports. After struggling somewhat last year, Stanford football currently ranks 15th in the nation. Again, is this coincidence or causation at work? USA Today reports that several major universities, along with the Dallas Cowboys, were convinced enough by these numbers to purchase the technology for themselves.

Meanwhile, other collegiate teams have hired EON Sports, another startup that uses video game graphics for a Madden-esque VR setup. Unlike STriVR, which has to physically record different play calls for QBs to train against, EON's artificial setup allows coaches to create their own defensive schemes for their quarterbacks to face. Whether painstaking realism or flexible interactivity will win out remains to be seen.

How much do these systems cost? Virtual reality has become much more affordable now that Oculus has made developer kits readily available, but the costs may still be prohibitive for some teams. EON Sports offers "High School and Youth Level Pricing" with costs ranging from $499 to $999, suggesting the professional offerings cost much more, and we can only assume STriVR's lifelike product likely costs much more. It's therefore unsurprising that mostly affluent universities like Stanford have adopted VR thus far: colleges strapped for funds may take years to justify such purchases to budget committees. Where the NFL's equally wealthy teams have no problem investing in this technology, the NCAA might see a fairness issue arise in the years to come if VR proves to be as consistently advantageous as Belch claims.

Image Source: Bleacher Report

The Olympics

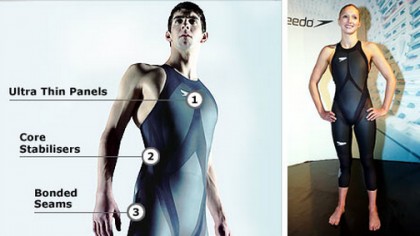

Olympic events ban wearable tech during the Games to prevent countries using their wealth to gain an advantage on the track - for instance, forbidding Speedo's LZR Racer swimsuits at the London 2012 Games - but that hasn't stopped teams from using wearables to train before their events, to proven success.

During the Sochi Olympics last year, Catapult Sports proved it could track more than athletes, as its Minimax S4 sensor allowed the US snowboard team, which won three gold medals that year, to gauge the g-force of their tricks on the half-pipe and determine points of emphasis on perfecting their McTwists and 1080-degree airs. Ice skaters used body suits outfitted with sensors to create 3D recreations of their routines and improve their biomechanics. And several athletes wore Hexoskin, a full-body suit that sends vitals and G-force data to your smart device during training, including eventual mogul skiing gold medalist Justine Dufour-Lapointe.

The Olympics may only allow amateur competitors, but it is common knowledge that athletes backed by wealthy athletic teams and sponsors tend to have an advantage, giving competitors from certain countries, like the United States, an edge. Access to wearable technology is an extension of that nationally based privilege.

Image Source: BBC

Golf

If there's any sport that was destined to inspire an endless supply of fancy wearables, it was the gadget-happy and technique-focused sport of golf. Golfers have used video replay and 3D swing modeling for years in high-tech studios, but now wearables are making these resources available on the course itself, and at a price affordable to both professionals and amateurs.

Acclaimed golfers like Jim Furyk and Lee Westwood use Game Golf, which attaches coin-sized sensors to the belt and each club grip to track where the ball went, how many putts and sand saves per hole, and other data before sending it to the player's mobile device. For golfers that don't want a distracting foreign object on their clubs, they use Zepp Golf, a lightweight sensor in their glove that senses clubhead speed, hip rotation, and club positioning to send a model of each stroke to players' devices. And to prepare for the hazards of unfamiliar courses, players play practice rounds with Garmin, a golf-centric smartwatch with layout and hazard data on 39,000 courses worldwide.

But these gadgets can't be brought into tournament rounds, and can only help your technical game, not your mental game. For that, players like PGA Championship winner Jason Day use iFocus band, a sensor placed inside golfers' hats that illustrates brain activity and stress levels over the course of a round on a smart device. By pinpointing which parts of the game put the most stress on players' swing (in my case, putting), it trains golfers to recognize and overcome the stressors that derail their rounds. Day won five tournaments this year after winning two the previous nine years, so one could argue this tech has had a positive effect on his game.

Most golf wearable tech has been specialized so far, but the major wearables players are starting to throw their hats into the ring. Microsoft Band 2 comes equipped with Golf Tile, a first-party app co-designed by Taylormade that tracks a player's score for a round by differentiating between practice and real swings and sensing via GPS data when they've finished a hole. After each round the data can be transferred to Taylormade's myRoundPro, which analyzes trends in a swing over time to improve slices and hooks. The Apple Watch has no first-party golf apps, but it does support Golfshot, which provides GPS data of distance to holes and hazards on specific courses.

Image Source: PGA Tour

So are teams buying wearable wins?

It's honestly hard to say. Are teams really winning games because of employing wearables during preparation that substantially improve their results, or would they do just as well without the devices? Athletes and coaches will probably never verify just how important technology is to their success because it takes away from the narrative of hard work and passion leading to victory. And it may even be true that this technology is nothing more than an experimental novelty that doesn't really affect a team's chances in the long run. On the other hand, the small sample size of statistics and anecdotes above does suggest that teams get better after starting to use wearables, and that it's teams with money to burn on wearables that are most comfortable testing this theory.

The question is, are wearables different from any other technological advantage?

Sports teams are generally wealthy (some more than others) and pay as much as necessary to find the latest small advantage for their players. The richest teams may be more capable of buying experimental technology first and reaping the rewards, but their rivals will almost always immediately follow their lead to close the gap. That's why even if some teams have gained an advantage with wearable tech through early adoption, it's highly likely other teams have noticed and will soon follow suit, if not one-up them with even newer and more advanced technology. Within a decade, I predict every professional team will be openly using wearables. Of course, college sports are more likely to support unfair financial imbalances, and fans of schools with less cash to spend on sports teams should be wary of wearables' advantages.

Ultimately, wearables are most exciting in the field of amateur sports because the devices are democratizing access to data and technology previously only available to, well, professional sports teams. The fact that this technology can allow anyone with a smart device to improve workouts, reduce the cost of hobbies, avoid injuries, or overcome disabilities shows wearables' great potential.

Image Source: Wareable

Michael Hicks began his freelance writing career with TechRadar in 2016, covering emerging tech like VR and self-driving cars. Nowadays, he works as a staff editor for Android Central, but still writes occasional TR reviews, how-tos and explainers on phones, tablets, smart home devices, and other tech.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful