Napster launched 25 years ago today – and Spotify is making me miss it every single day

Napster let us roam free, but Spotify locks us into a walled garden

25 years ago, on June 1 1999, Shawn Fanning’s idea of a peer-to-peer file sharing network was born after he teamed up with his teenage chat room pal and self-taught tech genius Sean Parker.

The pair’s program, Napster (Fanning's hacker screen name), allowed anyone with a free account to share music from their hard drives with all other Napster members, instantly creating the world’s largest and completely downloadable free music library. Numbers grew rapidly, and at its height Napster had approximately 80 million users.

For a music industry that seeks to monetize every note that reaches our ears – until 2019, singing 'Happy Birthday' to someone without paying a royalty fee was technically illegal – Napster was anathema. To the rest of us, it was heaven.

Together in Electric Dreams

Free music was not a new idea. Previously, the only thing stopping anyone was how hard it was to get – all that taping records and songs off the radio, or ripping CDs, was quite time consuming.

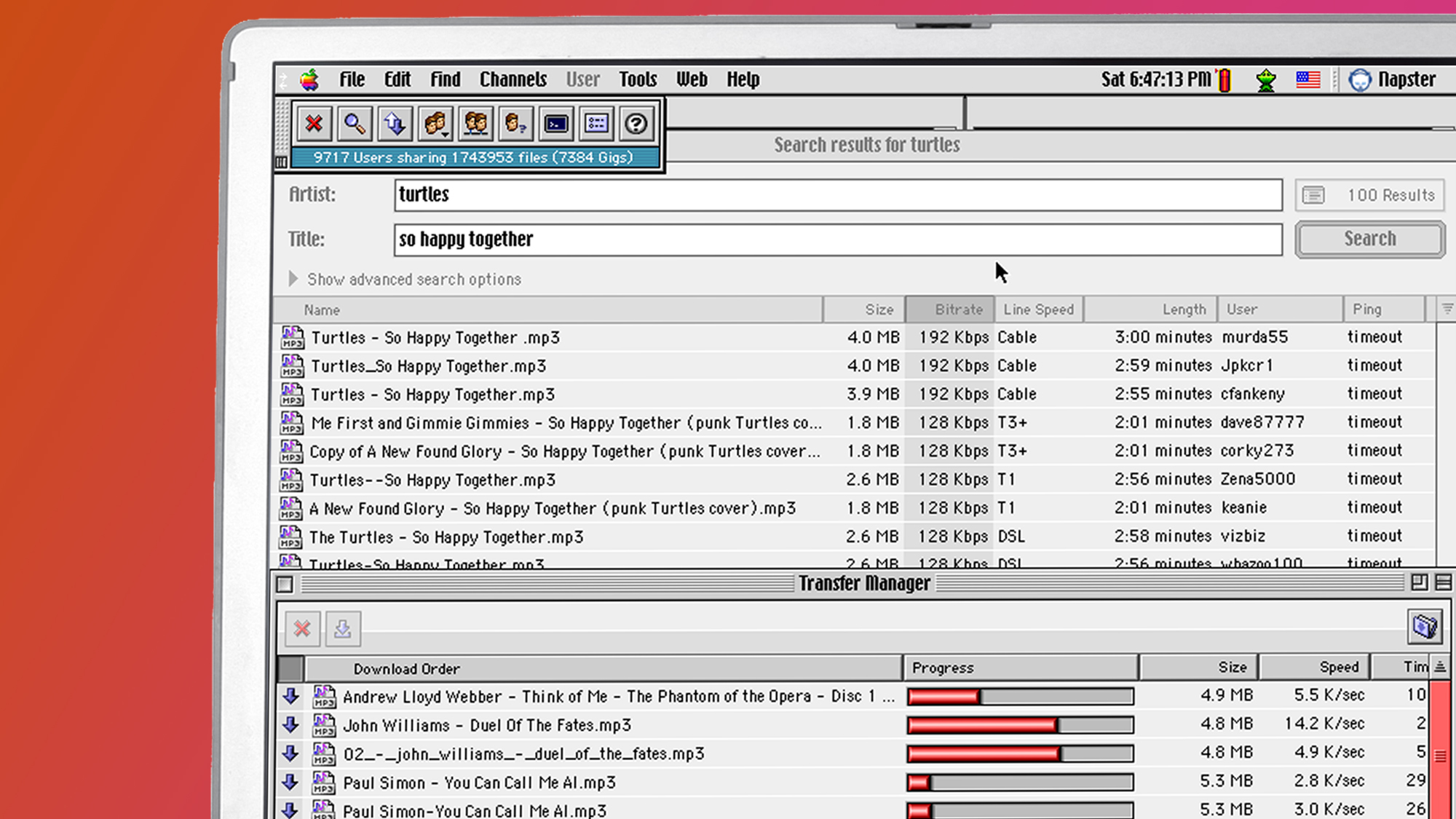

Napster made it easier – I want to put Together In Electric Dreams on a playlist? Right, I’ll instantly download it from Napster. Well, in 23 minutes, according to this progress bar.

In hindsight, I can understand why the overprotective music industry behaved how it did and crushed Napster after less than three years.

I loved Napster. It felt like the corporate front doors had been kicked down and after years of being held back, we suddenly had access to anything we wanted.

There is a turn-of-the-century news report showing an interviewer asking a group of teenagers on a college campus how many songs they’ve downloaded – 600 boasts one, "maybe 100 or something" says another, before, to the incredulity of the reporter, one student claims they now have 6,000 free songs on their computer.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

To the music industry at the time, those 6,000 songs were the equivalent of $6,000 in lost sales – the reality was that student was never going to spend $6,000 on music.

Beg, Steal or Borrow

In the year 2000, I was nearly fired for downloading Napster at work. At this time I was working at a music news website owned by some former music industry bigwigs. Among the articles I put forward the opinion that Napster might be the future. It didn’t go down well. It wasn’t so much that they didn't think downloads were the future, just the more logical point of view that Napster was illegal and stealing.

I disagreed, it was borrowing.

I loved Napster. It felt like the corporate front doors had been kicked down and after years of being held back, we suddenly had access to anything we wanted – just so long as we could remember what it was we wanted.

Not for one second, as I downloaded a live version of a song I already owned on vinyl, did I worry that I was withholding money from the artist, but maybe I should have. Somehow I didn’t think they’d mind. But many musicians – notably Metallica – really did and it was their opposition to file sharing that killed the Napster dream.

There is no doubt that Napster helped expand musical horizons – it made all genres and eras accessible in a new way and for many artists it expanded their fanbases and led to increased sales. Radiohead's Kid A album and Moby's Up, for example, benefited from its power.

Not for one second, as I downloaded a live version of a song I already owned on vinyl, did I worry that I was withholding money from the artist.

In an interview at the time, Dave Grohl of the Foo Fighters mocked millionaire artists "bitching" over lost pennies from Napster and said that yes, fans should pay for physical products like CDs and vinyl, but that music should be free. “I don’t want to turn on my radio and pay a nickel to hear Metallica,” he said.

And that, really, is all Napster was. A big radio.

25 years on, Metallica’s victory is that instead of paying $0 to listen to their song via Napster, today if we listen on Spotify they’ll get $0.003 to add to their pile. But the reality is that musicians like Metallica missed out on the far bigger pay day they could have received.

Party like it's 1999

Napster was something that Spotify has never been – it was fun. And while it was destroyed for flouting copyright laws, I’ll continue to argue that it was closer to the spirit of music fandom and an artist’s creativity than any streaming or downloading platform that has come since.

Before being finally kicked out of existence in the US courts, there was a moment when the music industry could have worked with Napster and understood that here was a brilliant new form of distribution – and if musicians were going to take a truly revolutionary step, a way for artists to get their music directly into the ears of their would-be fans was bypassing the music industry completely. The opportunity was missed.

The more Spotify grows and moves away from music discovery the more and more I miss Napster – and I should clarify, seeing as the brand still exists, I mean the OG Napster of 1999 to 2002. I miss what it was and what it could have been; a musical distribution service that was affordable to the consumer and actually paid musicians fairly.

Without Napster creating so many millions of digital music users, Apple and the iPod would not have had such a vast readymade customer base.

The crushing of Napster spawned copycat after copycat until Apple cracked the code and persuaded the music industry to buy into its store. Napster rewired our brains and taught millions how to download. Without Napster creating so many millions of digital music users, Apple and the iPod would not have had such a vast readymade customer base nor would we have today's best music streaming services with their illusion of free content.

Islands in the Stream

There is a direct line between Napster and Spotify.

Sean Parker had a storied career after the demise of Napster, becoming an investor in numerous companies, including Facebook, where he served as president until a drugs bust – over which he was never charged – led to his departure. He then became a board member at Spotify, where he remained until 2017.

I do enjoy Spotify and there are some brilliant things you can do with it, I just wish it wasn't so bloated. Today, I find it all a bit too try-hard – the algo, the playlists, the suggestions, the end of year wrap, the way it is impossible to escape from Taylor Swift.

With Napster I was left to my own devices, free to roam in the universe’s biggest record store to play whatever I wanted. On Spotify I feel as if I am being followed by an over-attentive store detective who isn’t worried about me stealing, but is very concerned by the amount of miserable music I listen to.

Increasingly I think of Spotify as less like a super-abundant walled garden that one would never want to leave and more like an endless maze I can’t escape, with paths, diversions and interesting detours but where all routes inevitably lead me back to the familiar.

Napster was far from perfect, but unlike anything since it allowed me to get lost in music. I miss that feeling.

You might also like

Johnny is a freelance pop culture journalist who has been writing about the internet, music, football and famous people since the iPhone was just a twinkle in Steve Jobs' eye. Previously known by the pseudonym the Pop Detective, his journalistic career began making up stories about Madonna's addiction to sausage rolls (this is not true by the way). A man of few talents, his career is rich and various and includes the highs of interviewing Elton John and Blur; and the lows of interviewing Right Said Fred, appearing on a Channel 5 documentary about Peter Kay, and fact-checking the instruction manual for a German cooker. Somehow still affording to live in North London he is at his happiest riding his bicycle and shouting at pigeons.