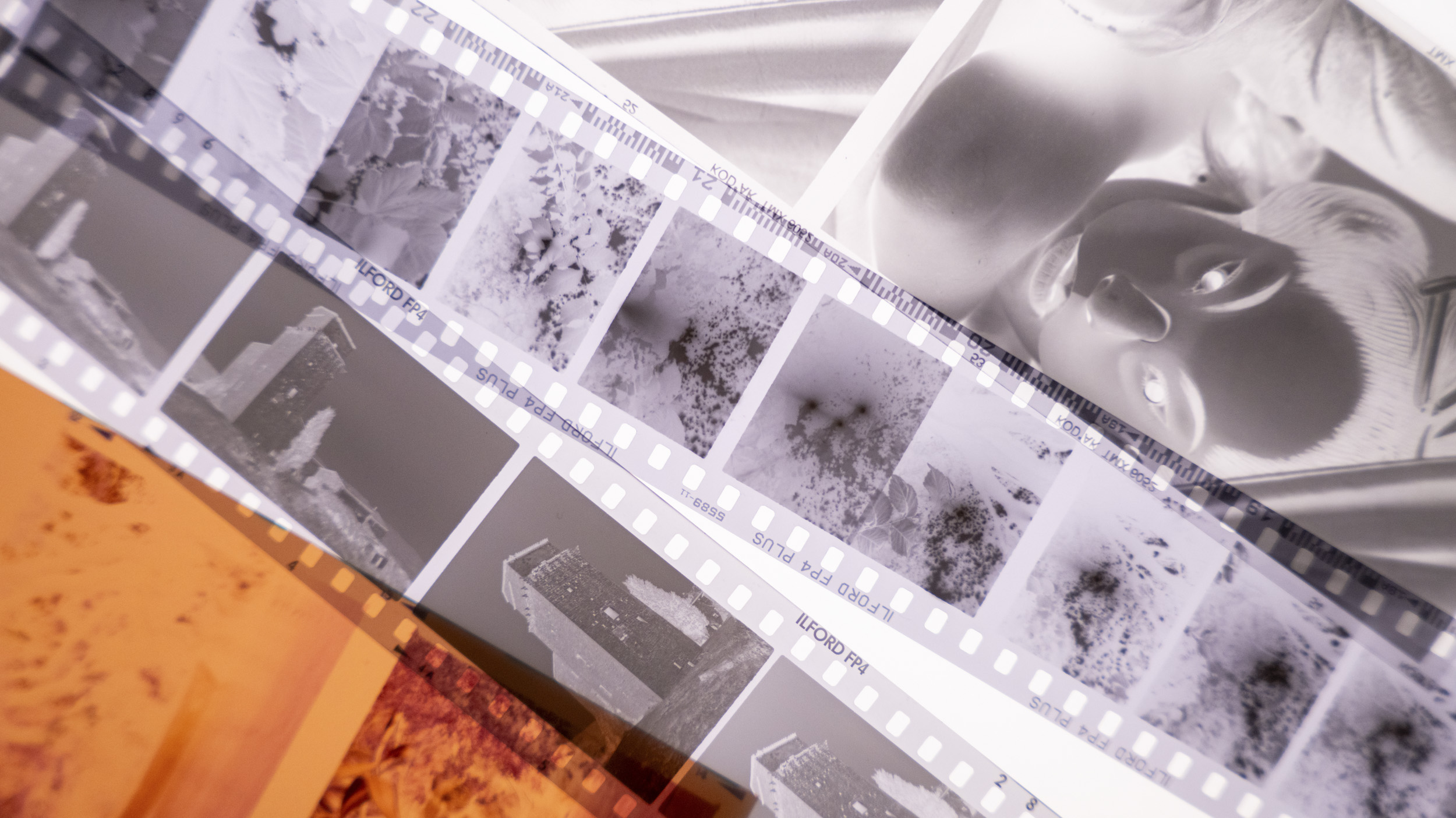

In the old days—well, actually not that long ago—photographers had no choice but to use film. There was simply no other way to make a photograph. This was cool, and we didn't know any better anyway. However, these days, shooting film is a creative choice that is growing in popularity. Perhaps, like vinyl, it’s the allure of the analogue vibe, the physicality of handling an actual material, or the alchemic magic inherent in the old-school methods which inspire this revived interest.

Regardless of motivation, using film requires a little more consideration than simply selecting a film emulation preset on your camera’s menu. In the first instance, you will have to purchase film, and that means making a bunch of creative decisions in advance. The type and size of film you buy depends on a whole lot of parameters, which we’ll discuss here. Aside from the size of the film, which is determined by the camera you use, you’ll also have to commit to the film’s ISO rating and decide whether you want to make black and white or colour photographs and if you decide on using colour, do you want to use transparency (slide) film colour negative and whether it’s been ‘balanced’ for daylight or tungsten light.

Shooting with film can be great fun. It’s a slow, magical process and offers something that digital photography lacks. If you have time, creative curiosity and a spot of spare cash, it can be rewarding. But be warned, it can be a rabbit hole of expense as the costs of film and processing increase, but it’s worth it!

Film sizes explained

If you're interested in buying your first film camera, you should first consider the film size you'd like to shoot with because each has its own advantages. The following options that I've covered below are the most popular.

We've ranked the best cult cameras ever and also compiled the best film cameras into a handy guide if you'd like to see our favorite film cameras.

35mm

35mm film has become the standard photography film size; it was initially developed for movie-making in the late nineteenth century. However, Oskar Barnack of Leica Cameras appropriated and adapted it for the first Leica 35mm film camera in the 1920s. With a 2:3 aspect ratio, it soon became the standard mainstream film used worldwide. The smallness of the film and its easy-to-load-into-a-camera cartridge meant that cameras could be made much smaller and, consequently, more portable. It was a pivotal moment in the history of camera technology, and its legacy is still evident today. It’s even the same size and aspect ratio as a full-frame sensor in many digital cameras (24x36mm).

A roll of film is typically 638mm long, which gives roughly 36 exposures. Sprocket holes on the edge of the film allow it to be advanced from one frame to the next, easily allowing 36 images to be made without any faff. It might not seem revolutionary now, but this made a big difference to photographers a century or so ago. Leica is still a trailblazer and makes both film and digital cameras, such as the Leica M-6. For less expensive options, check out the second-hand market for cameras, such as the Nikon F3 (a personal favourite of mine) or the less fancy Olympus Trip.

Half Frame

A ‘half-frame’ camera also uses roll 35mm film. However, a half-frame camera has been designed so the frame is orientated across the film instead of along it. This means you can effectively get twice as many images. So a standard 36-exposure film will allow you to shoot 70-plus frames. The smaller image size will adversely impact the image quality; however, with the ever-increasing cost of film and processing, this is an attractive option, and recent cameras, such as the Alfie TYCH and the recently reviewed Pentax 17, are proving popular.

Medium format

Medium-format film is bigger than 35mm but smaller than large-format sheet film (see below). The most common type is 120 film, which typically produces images with dimensions such as 60x45mm, 60x60 mm, 60x70 mm, or 60x90 mm. Its larger image area means that medium-format film could resolve more detail and information than 35mm, so professional photographers and serious enthusiasts gravitated to it and still do.

To get started, why not try a relatively inexpensive HOLGA 120N (in our cult cameras list)? It’s the plastic lens and toy-like construction that won't produce quality images, but they're fun. If you're more serious, look on the second-hand market for a Rolleiflex, Mamimia 645 Pro, or the classic Hasselblad 500C.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

110 film

110 film is a cartridge-based film introduced by Kodak in the early 1970s. The image size is a meagre 13x17mm. It was conceived for casual sappers, and the cartridge design makes it super easy to load into a camera. Naturally, with such a small area of film, the descriptive detail captured is a lot less than in other film formats, but for holiday snaps, this wasn’t an issue. While pretty rare these days it is still available. It’s now manufactured by Lomography who revived the 110 film cartridge in 2011 for cool and funky cameras such as the Lomomatic 110 film camera. You can also find second-hand ‘vintage’ 110 cameras online or by keeping a beedy eye open in thrift stores, charity shops and car boot sales for cameras such as the Prinz 110 Colorman camera.

APS

APS (Advanced Photo System) film was another cartridge-inspired concept introduced by Kodak in the mid-nineties. Ease of use for everyday consumers was the motivation, along with some innovative ideas. For example, APS film featured a neat magnetic strip that stored some data, such as date and time stamps. It seems pretty primitive in today’s world of geotagging and so on, but it was pretty awesome at the time. APS film has been out of production for over a decade, so it’s unlikely to crop up on your radar. There may be out-of-date film stock knocking around on auction sites, but it also requires specialist processing equipment, so unless you’re a fanatic about it, leave it in the history books.

Instant film

Instant films such as Polaroid and Fujifilm Instax are seeing something of a revival, especially with consumer photographers hankering for a retro groove. Polaroid film was invented by Edwin Land in 1947, and until digital photography became mainstream, professional photographers would often use a Polaroid to ‘proof’ their shoot as a way to check lighting and exposure. It also had a massive appeal in the consumer sector, and few family albums don’t have at least some instant prints on their pages. Fujifilm has an extensive range of popular Instant cameras such as the Instax SQ40, Instax mini 99, and Polaroid revived itself with the Polaroid I-2 and the Polaroid Now series; even better are the hybrid digital/instant cameras such as Fujifilm Instax mini LiPlay, Instax mini Evo (which the Leica Sofort 2 is based on) which combine the best of both old and new technologies.

Large-format

Large-format film typically comes in sheet form; the standard size is 5x4 (127x102mm) inches, but bigger sheets such as 8x10 inches (254x203mm) are also used. This is a pretty massive piece of film, and the descriptive detail that can be captured is staggering. It is, however, exceptionally expensive and tricky to handle.

Historically, advertising, architectural, landscape and art photographers gravitated to large format film and cameras for the staggering amount of detail that could be captured and the consequent ability to make large prints or billboard posters. Large-format cameras are cumbersome and fiddly to use, and the cost of the film is eye-watering. Aside from the amazing level of detail that can be captured, most large format cameras also allow the lens and film plane to be swivelled, tilted and shifted independently of each other. This makes it an ideal, albeit complicated, tool for architectural photographers needing to keep things straight and vertical.

Film types explained

ISO

Unlike a digital camera, where you can change ISO with the twist of a dial, committing to the film's ISO requires more considered attention at the point of purchase, and once it’s in the camera, there’s no changing it to accommodate a shift in lighting conditions. Typically, the range of ISO films on offer is much smaller than can now be achieved with digital sensors: 100, 200, 400 and 800 being the standard ratings. There are high ISO films such as the Ilford Delta 3200, but the ‘grain’ (think - digital noise) is the size of golf balls.

Colour or Black & White

As with ISO, other creative decisions, such as shooting in black and white or colour, need to be made before loading your camera, too. And once the film is in, you’re pretty much committed. The choice isn’t just limited to ISO and colour or black and white; you also have the choice of colour transparency film (slide), colour negative film and colour film that’s ‘balanced’ for daylight or tungsten, and different black and white and colour films have different characteristics too. There is too much to list here, but look at any set of film emulation presets for image editing software to get a sense of the myriad options available.

If you’re on a budget, black and white can be more viable as, with a little practice, it’s relatively easy and cheap to process a roll of film at home without needing a darkroom.

You might also like

Benedict Brain is a UK-based photographer, award-winning journalist and author. He balances his personal practice with writing about photography and running photography workshops and enrichment programmes. He writes a monthly column called The Art of Seeing, and his first book, You Will Be Able To Take Great Photos By The End of This Book, was published in 2023 by Ilex Press in the UK and by Prestel in the USA with translations in Spanish, Bulgarian and German; his second book, A Camera Bag Companion, was published in March 2024. Benedict is often seen on the panels of prestigious photo competitions, and in 2020, he founded Potato Photographer of the Year. Benedict exhibits his work internationally, and travels the world as a public speaker, talking about the art and craft of photography.