Social media blocks are "a suppression of an essential avenue for transparency"

At least 50 countries have been restricting platforms since 2015

Once praised as the defining feature of the internet, the ability to connect with physically distant people is something that governments have recently been seemingly intent on restricting. Authorities have been increasingly pulling the plug, putting over 4 billion people in the shadows in the first half of 2023 alone.

Social media platforms are often the first means of communication to be restricted. Surfshark, one of the most popular VPN services, counted at least 50 countries guilty of having curbed these websites and apps during periods of political turmoil such as protests, elections, or military activity.

The company has recently released some new statistics on the matter, so I spoke with one of the researchers to understand more about this worrying trend and what's at stake.

Social media restrictions in numbers

As mentioned, 50 nations have reportedly pulled the plug on popular social media services like Facebook, Instagram, X, and TikTok in the past eight years. However, there are some governments that went the extra mile in repressing their citizens' digital life.

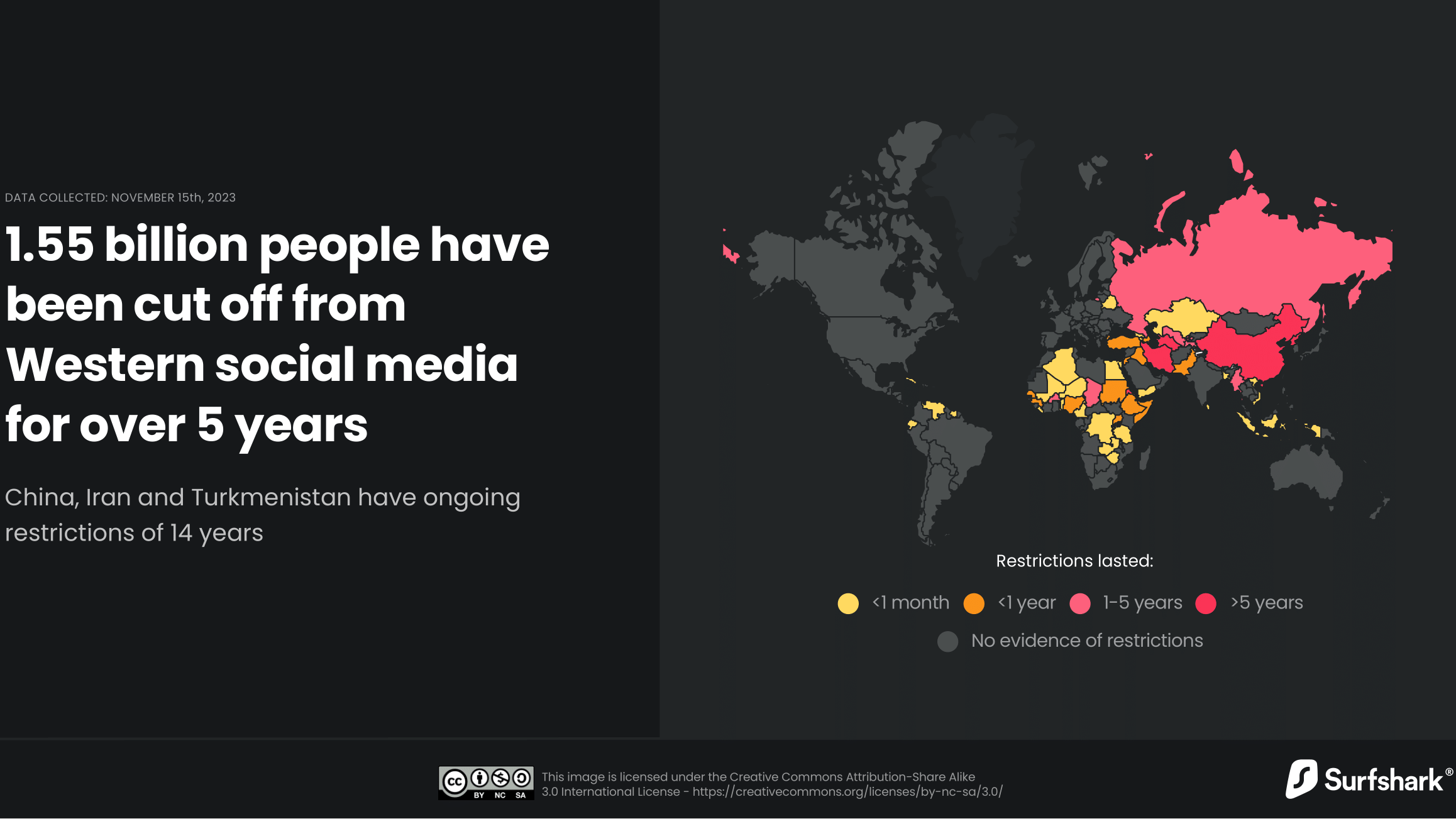

"Five countries have experienced the longest restrictions (lasting more than five years). Although that may not sound like many countries, it translates to 1.55 billion people," Lina Survila, Surfshark spokeswoman, told me while commenting on the findings.

People living in China, Iran, and Turkmenistan have not been able to access Facebook, YouTube, or X for 14 years now. In Eritrea, YouTube went dark 13 years ago and never recovered. North Korean nationals could never access Western social media platforms, and Instagram went dark for visitors as well eight years ago, followed by all other major platforms at a later date.

"The fact that so many people have been deprived of social media access by their governments for such a long period is what shocked me the most," Survila told me.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Elsewhere, around 2.3 billion people have experienced restricted access to social media for an average of 4126 hours (about half a year). In Russia, for example, people have been facing restrictions on Facebook, Instagram, and X since the invasion of Ukraine began, while other countries enforced short-term information blackouts during times of political turmoil.

In 2023, Turkey blocked Twitter for just two days, but it was when people needed it the most: in the aftermath of the devastating earthquake that killed over 15,000 people in both Turkey and Syria.

Ethiopia has not had access to popular social media sites since February 2023 amid protests over the split of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, while people in Senegal turned to secure VPN services in June to cut through the thick blanket of censorship.

In Western countries, social media platforms are often seen in a negative light. These platforms are thought to distort users' views on important political topics, endanger children in different ways, and promote a rather superficial lifestyle.

The truth is that these platforms are far more powerful when used in the right way. They enable people to access news in real-time, exchange opinions, and keep the information flow going. All this is especially crucial during times of crisis. Authorities know this very well, and that's precisely why they might decide to block their access, curbing citizens' freedom of speech in the process.

Survila told me: "Restricting these platforms isn't simply a limitation on social connections—it's a suppression of an essential avenue for transparency, potentially allowing government propaganda to dominate without opposition."

Asked how the trend has developed over the years, she said to have not noticed any clear increase in the number of restrictions imposed. At the same time, there was not a decrease either. According to Survila, this means that social media blackouts still remain a common tool among autocratic leaders to silence the public and hinder the spread of information.

She said: "It’s unlikely that the countries imposing decade-long restrictions will retract them anytime soon. It also doesn’t look like the number and frequency of new restrictions will slow down in the near future."

Even worse, perhaps, this worrying censorship wave might not even remain an exclusive prerogative of certain despotic governments for long. Also some so-called Western democracies have been showing a will to gain greater control of how people communicate online.

The US took a strong stance against TikTok at the start of the year, which led to the state of Montana to issue an outright TikTok ban for all citizens. This was supposed to be enforced starting from January 1, 2024, but it was blocked by the federal district court on November 30.

On the other side of the Atlantic ocean, France's SREN Bill plans to boost internet censorship to combat online fraud. President Macron (backed up by EU Commissioner Thierry Breton) even called for social media shutdowns if these platforms failed to quickly delete hateful content during riots under the new Digital Service Act.

On this point, Survila said: "Harmful and abusive content should undeniably be eliminated from online platforms, and it's important that social media companies and governments implement strong measures to identify and remove such material. But it’s also crucial that we preserve individuals' access to social media. Banning entire platforms is certainly not the right solution."

How a VPN can help

Short for virtual private network, a VPN is security software that both encrypts internet connections and spoofs your real IP address location. The latter ability is exactly what you need to bypass social media restrictions. It tricks your ISP to think you're browsing from a completely different country entirely, granting you access to Facebook, Instagram, or any other platforms despite this being blocked.

While citizens living under such a digital suppression learned how to navigate restrictions, also governments are getting savvy enough to prevent them from evading these blocks. VPN censorship is on the rise as well, in fact, with China and Iran gaining the crown as the biggest offenders worldwide in 2023.

That's why I suggest downloading several apps to hop from one to another in case these get blocked. I recommend checking TechRadar's best free VPNs page to choose the safer freebies on the market. Additional tools like the Tor browser can also help here, as well as less-known software like Snowstorm and Lantern.

On its side, Surfshark developers have equipped the software with some censorship-resistant features like its Camouflage mode to escape VPN blocks and No Borders which automatically connect you to the servers performing the best under network restrictions. At the same time, its researchers are committed to keep shed light on this dangerous practices to put some pressure on countries' leaders.

Survila said: "By releasing our studies and raising awareness of social media restrictions, we hope to encourage people to talk about them. In this way, we hope to gradually build public pressure against the authoritarian regimes responsible for imposing these restrictions, leading them to reconsider and potentially cease such actions."

Chiara is a multimedia journalist committed to covering stories to help promote the rights and denounce the abuses of the digital side of life – wherever cybersecurity, markets, and politics tangle up. She believes an open, uncensored, and private internet is a basic human need and wants to use her knowledge of VPNs to help readers take back control. She writes news, interviews, and analysis on data privacy, online censorship, digital rights, tech policies, and security software, with a special focus on VPNs, for TechRadar and TechRadar Pro. Got a story, tip-off, or something tech-interesting to say? Reach out to chiara.castro@futurenet.com