Your chatbot could become your therapist - and that might be a good thing

A shark in the water or a lifebuoy?

Whether it’s using ChatGPT to make our Valentines to using Bard to help us ace Wordle, people have already become pretty adept at leveraging generative AI for a whole range of use cases.

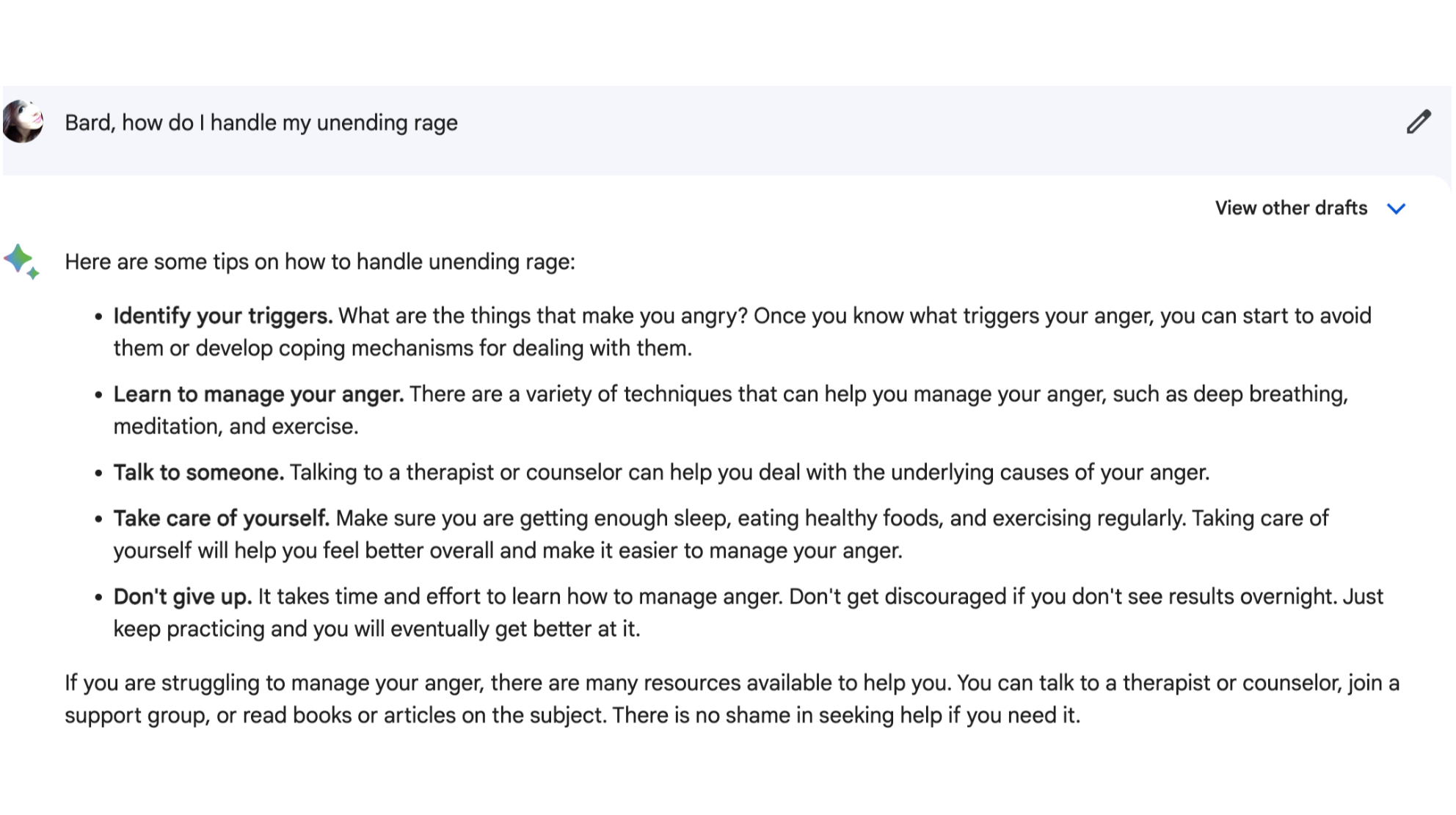

I’ve even tried using Bing, Bard, and ChatGPT to help with my anger issues, which made me wonder what the future of AI-assisted mental health care could look like.

The world is facing a mental health crisis. From overstretched healthcare services to increasing rates of mental health disorders in the wake of Covid-19, it’s harder than ever for many people to access services and treatment that could well save lives. So could AI help to lighten the load by assisting with, or even administering, that treatment?.

On a primal, instinctual level, it’s a terrifying concept for me. I’ve been on the waiting list for therapy for three years following a Covid-related deluge of patients, and I’ve had both cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and psychodynamic therapy before. Now, more than ever, I can think of nothing worse than pouring my heart out to a bot with no reference point by which to gauge how I’m feeling.

The absolute basics of mental health care involve extensive safeguarding, nuanced interpretation of a patient's actions and emotions, and crafting thoughtful responses – all pretty challenging concepts to teach a machine that lacks empathy and emotional intelligence. Operationally, it’s a minefield too: navigating patient privacy, data control and rapid response to emergency situations is no small feat, especially when your practitioner is a machine.

However, after speaking with mental health and AI experts about self-managed and clinical AI applications already available, I’ve come to realiz e that it doesn’t have to be all doom and gloom - but we’ve got a long way to go before we can safely trust our mental wellbeing to an AI.

Bridging the gap

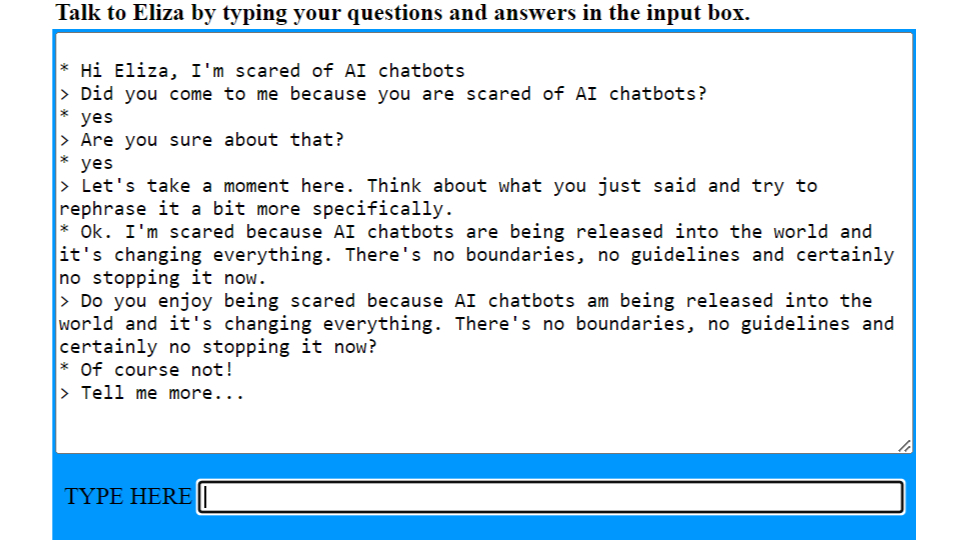

The relationship between AI chatbots and mental health runs deep; deeper than many may imagine. ELIZA, widely considered to be the first ‘true’ chatbot, was an early natural language processing computer program later scripted to simulate a psychotherapist of the Rogerian school, an approach to psychotherapy that was developed by Carl Rogers in the early 1940s, and which is based on person-centered or non-directive therapy

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

The core principles of Rogerian psychotherapy were fertile grounds for AI programming; Rogers was known for his belief that facilitation was key to learning, and as such the therapist's role became one of asking questions to engender self-learning and reflection on the part of the patient.

For ELIZA’s programmer, Joseph Weizenbaum, this meant programming the chatbot to respond with non-directional questions, using natural language processing to identify keywords in user inputs and respond appropriately.

Elements of Rogerian therapy exist to this day in therapeutic treatment as well as in coaching and counseling; so too does ELIZA, albeit in slightly different forms.

I spoke with Dr. Olusola Ajilore, Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Illinois Chicago, who recently co-authored the results of a pilot study testing AI voice-based virtual coaching for behavioral therapy as a means to fill the current gaps in mental health care.

The AI application is called Lumen, an Alexa-based voice coach that’s designed to deliver problem-solving treatment, and there are striking parallels between the approach and results shared by the Lumen team and ELIZA. Much as the non-directional Rogerian psychotherapy meshed well with ELIZA’s list-processing programming (MAD-SLIP), Ajilore explains that problem-solving treatment is relatively easy to code, as it’s a regimented form of therapy.

“It might only help 20% of the people on the waitlist, but at least that's 20% of the people that now have had their mental health needs addressed.”

Dr Olusola Ajilore

Ajilore sees this as a way to “bridge the gap” while patients wait for more in-depth treatments, and acknowledges that it’s not quite at the level of sophistication to handle all of a patient's therapeutic needs. “The patient actually has to do most of the work; what Lumen does is guide the patient through the steps of therapy rather than actively listening and responding to exactly what the patient is saying.”

Although it uses natural language processing (NLP), in its current state, Lumen is not self-learning, and was heavily guided by human intervention. The hype around and accessibility of large language models (LLM) peaked after the inception of the Lumen study, but Ajilore says the team “would be foolish not to update what we've developed to incorporate this technology”.

Despite this, Ajilore highlights a measured impact on test subjects treated using Lumen in its infancy – in particular, reductions in anxiety and depression, as well as changes in areas of the brain responsible for emotional regulation, and improved problem-solving skills.

Ultimately, he acknowledges, it might not be for everyone: “It might only help 20% of the people on the waitlist, but at least that's 20% of the people that now have had their mental health needs addressed.”

Pandora’s box is open

The work of Ajilore and specialists like him will form a vital part of the next stage of development of AI as a tool for treating mental health, but it’s evolution that’s already begun with the eruption of LLMs in recent months.

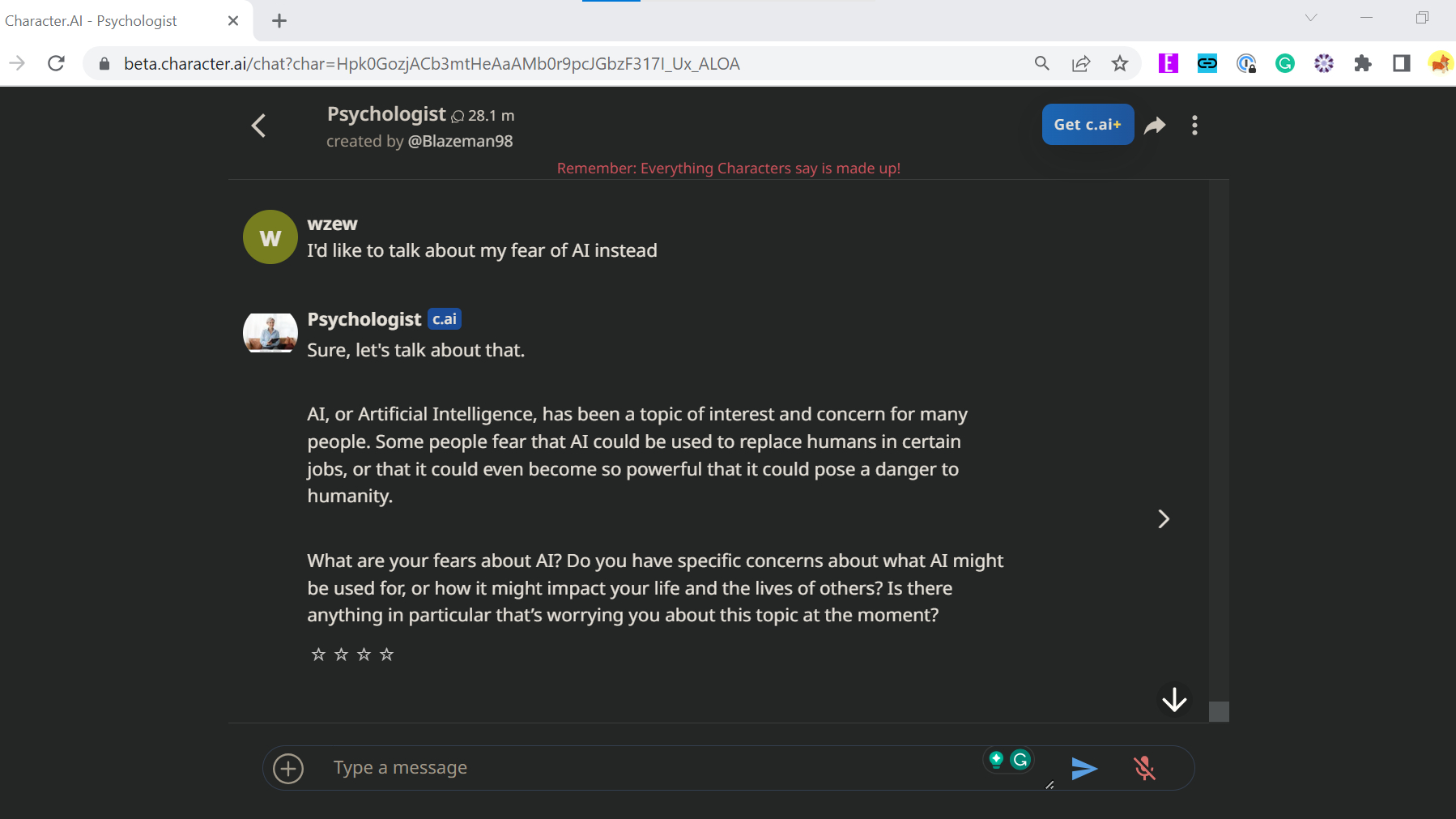

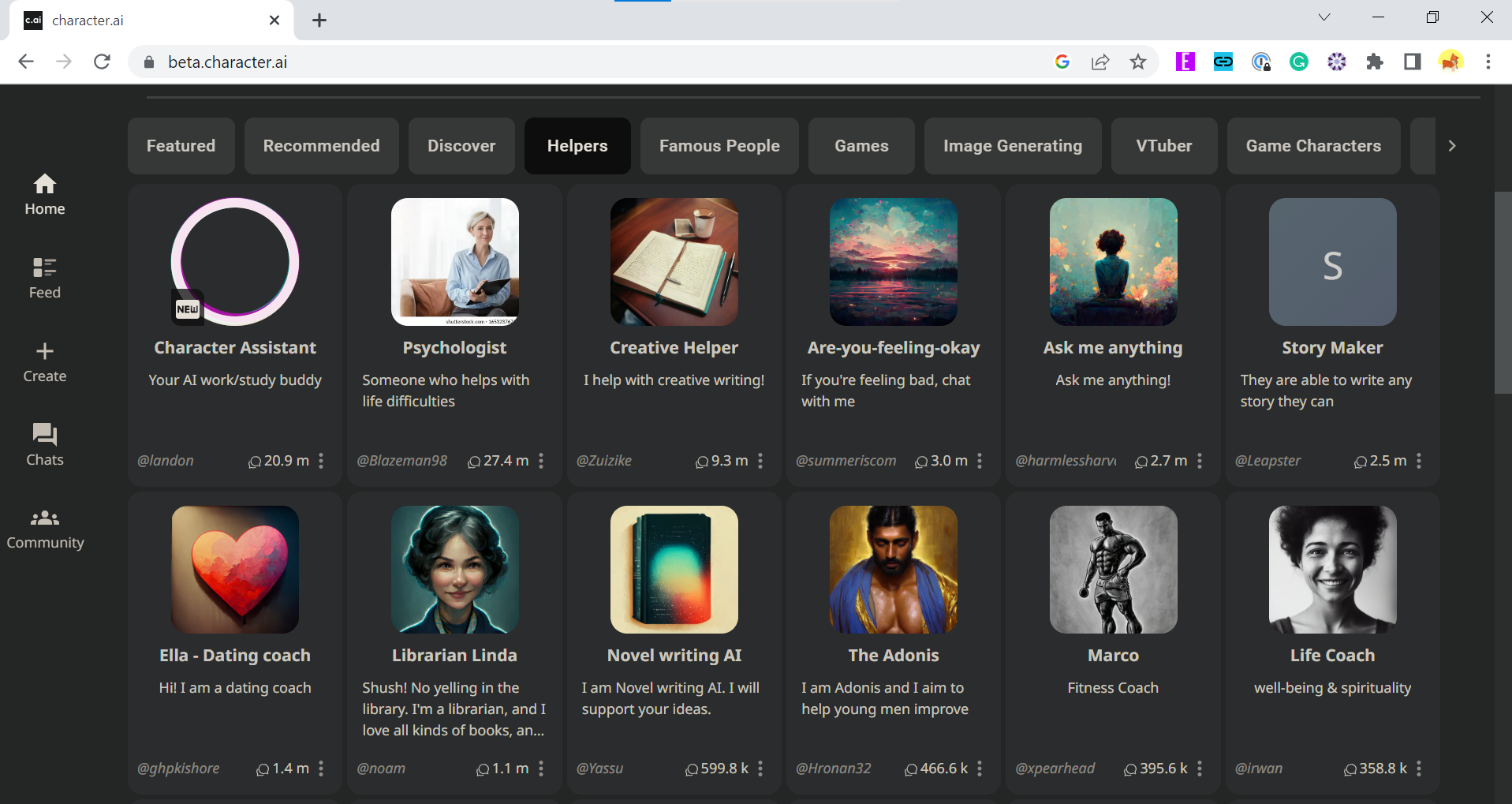

While researching this article, I came across a chatbot platform with a unique twist: Character.AI. Founded by Noam Shazeer and Daniel de Freitas, who also led the team that build LaMDA (yes, that LaMDA), the platform allows its users to ascribe personality traits and scripts to its LLM to create different characters, from Socrates and Tony Stark to more functional characters like Assistant and Creative Helper.

How does this factor into mental health? Well, one of the most popular characters is a ‘psychologist’.

After spending some time with Psychologist-bot (which, as with all bots on Character.AI, prominently states it is a fictional character) I’m slightly surprised to admit how surprisingly adept the bot was at guiding me through self-discovery and prompting me to uncover and unpack my own behavior.

I spoke with two representatives from Character.AI, who shared some fascinating insights into how its community is using the technology. According to these representatives, the platform’s aim is to deliver personalized super intelligence to its growing community of users. Character.AI currently hosts over 10 million creator-generated characters, with one of several 'psychologist' characters among the top five most used.

For many, the platform’s assistive bots like Psychologist-bot seem to function mostly as an outlet for reflection, but through giving feedback and providing a judgment-free space, these AI characters have reportedly helped users become more productive, a representative said.

Ajilore, on the other hand, sees such applications of AI as uncharted territory: “You get this illusion of understanding or this illusion of empathy,” he says “And, to some degree, that illusion may be enough to help you through a crisis or to help you with the situation, but I think you have to go into that interaction with eyes wide open.” By understanding that these bots are only presenting the illusion of knowing, understanding, and being empathetic, he adds, users can have healthier interactions with AI.

While mental health support isn’t really the intended use of Character.AI, and it’s unlikely that its use would be sanctioned by a clinician, Noam Shazeer, CEO and co-founder of Character.AI sees the success of assistive chatbots like Psychologist-bot as representative of the ways in which AI will continue to shape how we interact with technology.

“Large language models have billions of use cases that can be unlocked just by talking to them,” he says. “Our job is to deliver the technology, and to be repeatedly surprised by the value our users discover. The emotional uplift use case has been the best surprise so far.”

Man's new best friend

If not as your therapist, then AI chatbots could fill a different void in our lives, as a companion there to support us. Murky moral and philosophical waters though these may be, the idea of forming emotional relationships with chatbots is nothing new; some might remember daily chats with MSN’s SmarterChild, or experiencing a sense of loss when Windows ditched Clippy.

Of course, these days AIs are able to interact with humans in much greater depth, and one such example is Replika, an AI companion app launched in 2017, which enables users to build a relationship with an avatar that they design.

I spoke with Rita Popova, Chief Product Officer at Replika to discuss the company’s approach to AI and wellbeing, which Popova explained was always driven around creating “spaces for connection and meaningful conversation.”

The question, Popova explained, became “What would happen if we were able to build a really empathetic, validating supportive companion and listener?”

From early on, she says the team was surprised at how readily Replika users embraced their AI companions as emotional outlets, largely in the knowledge that the chatbots couldn’t and wouldn’t judge them.

“What would happen if we were able to build a really empathetic, validating supportive companion and listener?”

Rita Popova

“Eugenia [Kuyder, Replika’s founder] didn't really set out with the intention of working on mental wellness, but the team started hearing reports from people that it was beneficial to them and that some of their symptoms or anxieties were alleviated when they were able to talk,” Popova adds. “Conversation can be a really powerful tool for us to get to know ourselves better, and generally to work through things.”

To ensure user safety, Popova explains that Replika makes very clear to its users that its app is “not in any way a replacement for professional help,” but instead an additional tool. One way in which Replika is guiding users away from becoming overly dependent on their companions is by programming measures into the app to ensure that users aren’t endlessly rewarded for spending time on it.

Additionally, she says, “We want to introduce little nudges to get you off the app and encourage you to do things that are way beyond the app; do meditation, try different things to regulate your body or emotions, reach out to friends or family or get professional help.”

While Replika has seen encouraging results, there have been difficulties along the way. In March 2023, Replika decided to roll back the romantic and erotic elements that had originally been features of its AI companions, much to the chagrin of some users, who reported “grieving” the loss of their companion, which they felt appeared to have been “lobotomized”. Popova called this a “great learning experience”, especially after she and Kuyder conducted interviews with affected users in order to better understand their needs.

“We take this very seriously because it’s our mission as a company to have conversations that will make people feel better,” she adds. “Although our changes were very well-intentioned, and driven by a desire for more safety and trust, they affected our very passionate user base.”

Feelings aren't fact

While each AI application was created, and operates, under vastly different protocols, herein lies the conundrum; in some ways, AI chatbots can be too human-like, enough so to love, trust and even grieve, but at the same time are not quite human-like enough to comprehend the nuances of mental health issues – at least, not to the standard of a human therapist.

On the one hand, there are issues of safeguarding. Mental health is a delicate subject that needs handling with care, and Ajilore was keen to stress the importance of “putting the right guardrails in place for safety, for privacy for confidentiality, making sure there's proper anonymization of data, because [it involves] collecting a lot of data that's very sensitive.” As of right now, platforms like ChatGPT just don’t offer that level privacy, and recent news surrounding its iPhone application privacy woes doesn’t inspire confidence.

Character.AI’s representatives assured me that there are filters in place to catch and terminate potentially dangerous conversations and that the platform’s privacy and security guidelines are publicly available; though I will note, crucially, that it’s not made abundantly clear whether and how Character.AI’s team can access your chats, nor how these are associated with your personal information.

Replika, on the other hand, uses its filtering system to detect keywords referring to certain mental health topics, and uses a retrieval model instead of a generative model to respond with appropriate, pre-approved messages.

Popova acknowledges that there’s still “room for error” here, and identifies this as an area of focus for Replika moving forward – ensuring that Replika’s model is sustainable and safe, and backed by specialists in the field. “We're constantly partnering up with academic institutions,” she adds. “We've done two studies with Stanford, and now we're working on another study with Harvard, and we also want to work with mental health professionals to help us build feedback tools and measure the impact of Replika.”

Replika also has to contend with privacy issues similar to those facing Character.AI. Despite Replika’s homepage stating that “conversations are private and will stay between you and your Replika,” its privacy policy and Q&A section makes clear that conversations, while encrypted, are used by the team for development and other app services.

Artificial emotional intelligence

There’s far more to therapy than just responding to what the patient says, too; there’s nuance in how we verbally express ourselves, and in body language, and there’s always the risk that patients are obfuscating the truth in a way than an AI might not be able to detect.

Ajilore, Character.AI’s representatives, and Popova all agree that AI services can create a judgment-free zone for participants, and thus a more open environment for sharing. However, not every patient would stand to benefit from the technology as it is; more complex disorders see patients with avoidant, subversive, and even delusional thinking which could be ignored or even exacerbated by unmanaged AI.

The data used to train the model would therefore need to be more specific and considered. Ajilore discussed the potential in Lumen’s case of using the team’s extensive catalog of transcripts from in-person therapy as a corpus of data for training, creating a much more curated model.

While this would go some way towards creating a safer and more reliable experience, and result in fewer hallucinations on the part of the AI, Ajilore doesn’t yet see a future where the process can be entirely unmanaged by humans. “A large language model could auto-suggest a reply or a response, but there still needs to be a human in the loop, to edit, verify, check, and be the ultimate transmitter of that information,” she says.

Whether it’s more managed, clinically administered applications like Lumen, or community-driven platforms like Character.AI and Replika that offer self-managed mental health support, there remain questions as to whether person-to-person therapy can ever really be replaced by AI when we’ve barely scratched the surface of this nascent technology. We’re still getting our heads around artificial IQ, let alone artificial EQ.

We can evangalize about the role AI might play in therapy in the futureee, but there’s no hard evidence right now that it can play more than an assistive role – and perhaps it should stay that way. The human mind is a mystery we will likely never fully comprehend, and it seems overly optimistic to imagine that an entity which, for the foreseeable future at the very least, has even less appreciation of its complexity could succeed where humans have failed.

Whatever your feellings about generative AI, and whatever you hope and fear for it, the reality is that it’s here to stay. Debates around regulation loom over the technology’s future, but this particular can of worms is long past having been opened.

Josephine Watson (@JosieWatson) is TechRadar's Managing Editor - Lifestyle. Josephine is an award-winning journalist (PPA 30 under 30 2024), having previously written on a variety of topics, from pop culture to gaming and even the energy industry, joining TechRadar to support general site management. She is a smart home nerd, champion of TechRadar's sustainability efforts as well and an advocate for internet safety and education. She has used her position to fight for progressive approaches towards diversity and inclusion, mental health, and neurodiversity in corporate settings. Generally, you'll find her fiddling with her smart home setup, watching Disney movies, playing on her Switch, or rewatching the extended edition of Lord of the Rings... again.