Creating a metaverse for the people, by the people

Will the metaverse be a force for social good?

For four days in the middle of August, the Vancouver Convention Center is transformed into an uncanny valley. It looks like our world, but it’s not.

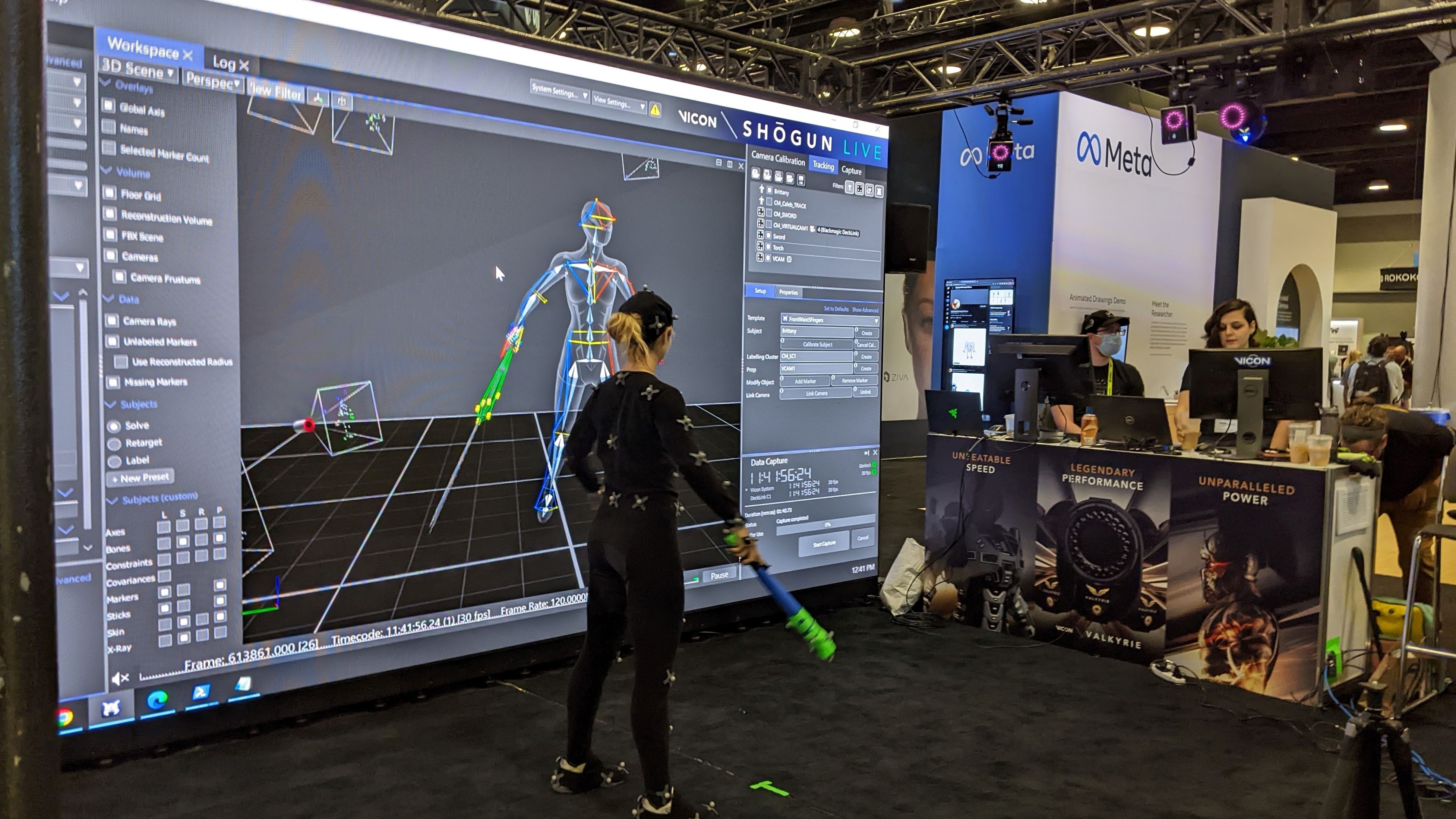

Siggraph, a conference for computer graphics and interactive techniques, brings together a community of VR, MoCap, VFX, animation and gaming tech-heads, all with the aim of creating a shared artificial world, or metaverse.

The metaverse promises to digitally capture and augment our lives. However, questions remain over the uptake of extended reality (XR) technologies, and just how desirable a virtual, interactive Second Life might be. Beyond these surface-level concerns also lies a deeper question: who controls the metaverse?

For these reasons, the concept is being treated with scepticism in some quarters, but not by motion capture company Vicon. The firm believes the metaverse will ultimately place powerful tools in the hands of those trying to better society.

“The basis of our company,” said Jeffrey Ovadya, Director of Sales, “is capturing human movement as accurately as possible to help heal the world. The output of our system will help them change their life for the better.”

Based in far-flung Oxford, UK, Vicon - which boasts ILM, Framestore, and Epic Games as partners - is at Siggraph 2022 to demonstrate the power of its new line Valkyrie cameras on an international stage.

Designed for motion capture, the camera tracks markers attached to a performer’s body, feeding a high-fidelity model into Vicon’s VFX software Shogun. The technology is mere microns away from laser-level accuracy; the top-of-the-line VK26 captures 26MP and native 150FPS.

Are you a pro? Subscribe to our newsletter

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

For Vicon, it’s all about reaching a broader audience, bringing the tech to new, smaller-scale industries. But can the drive to create a motion-captured metaverse that, in Blade Runner terms, is “more human than human”, really help to heal the world?

A grand vision

Asked to expand on the company’s lofty ambitions, Ovadya explained he believes the technology will not only be applied to high-profile use cases like Hollywood special effects or virtual reality gaming, but also become commonplace across a much wider range of industries.

“40% of our business is life sciences and biomechanics. The measurements and outputs of our system are going to be part of medical decisions to perform surgery on somebody,” he said. “If we can make that more affordable, more powerful, more accessible, more innovative, without encumbering [the user], we will continue to succeed.”

The pace of progress may be glacial for now, but the technology is beginning to filter down to smaller-scale businesses. It’s now in the hands of independent filmmakers, gaming studios, and V-Tubers streaming digital likenesses of themselves too. It’s all fun and games in the metaverse.

“One of the first sales I ever made in 2008 is still one of the coolest,” Ovadya told us. “Dr. Robert Wood at MIT, bought a system to track robotic flies that were used for reconnaissance and surveillance. So, we've got literally the size-of-a-house-fly drones with painted-on half millimeter markers flying around in the space, and you needed a 16-megapixel camera at a time to even think about doing something like this.”

The driving factor in Valkyrie’s development, Ovadya explained, was the demand from a constantly evolving industry with higher expectations and more specific use-cases than ever before.

“The concept of how people interact with technology is about a completely different form of UI and UX, your experience and your interaction with devices needs to be something where you pop it out, and it works just like this. We don't want you to get bogged down by the technology, if we can disappear and not be something that you have to actively think about.”

Instrumental in the development and design of the VK26, Vicon CTO Mark Finch fully supports making motion capture more accessible. “In my development perspective, it's about removing blocks. We will make it available and remove all of the barriers to development.”

Ovadya agrees: “I've been here 14 years, and I've seen just a dramatic shift towards a far more equity mindset in design. This is not for people that can only afford a certain amount, this is for anybody.”

The wider convention was awash with hardware and software designed to make tools accessible to new users and ultimately increase market uptake. Reps across the hall regularly invoked the triptych of AI, automation and efficiency. Everything promises to make you better, faster, stronger - and most of it does all the heavy-lifting for you.

Out of reach, or out of control?

Outside the exhibition center, along the harborfront, motion capture and the metaverse couldn’t have been further from the minds of the Vancouver residents. The pace was relaxed, unhurried, yet they moved with purpose, as if following some pre-programmed path. This is the world developers and artists are trying to recreate.

However, despite businesses and content creators embracing the metaverse vision in their droves, we can’t ignore the herd of elephants stampeding through the room. Chiefly, the fact the metaverse remains woefully out of reach to the general public.

“The problem is that it's not accessible for the average consumer,” Ovadya confided. “It is not comfortable enough to put on a VR headset in any environment and be a part of the metaverse. So, it needs to become more accessible on that front. Technology still needs to push forward so that it can be much more high fidelity, in real time.”

It’s our own weak and feeble bodies that are also to blame for the undelivered promise of a digital utopia.

“There needs to be some sort of regulation and an understanding that brains are not really made to handle the level of photon injection and stimulation that we're getting from a virtual Second Life,” he explained.

“We need to make sure that we have a better understanding of how it affects all of these things before we start saying everybody's ready for the metaverse. Once that's done, I do think that it's a powerful tool that can be used for good.”

Conversations around the regulation of the metaverse have already begun. One report highlighted three key regulatory themes: net neutrality, data privacy, and China's tech regulators who are resistant to both cryptocurrencies and Chinese developers' metaverse ambitions.

While new regulation will be welcomed by those who fear the metaverse will descend into a Wild West, forming a consensus is easier said than done. It will require the combined efforts of antitrust regulators, security regulators, digital rights bodies, and every other industrial, legal, financial and governmental body even lightly touched by the new digital order.

“I don’t want to get too political about this,” said Ovadya, holding up his hands. “But I do think, if we're talking about the democratization of all these other things as being beneficial for those industries, it should be the same for the metaverse. This needs to be something for the people, by the people.”

It’s a question, then, not of who owns the right gear, but who owns the metaverse. For Ovadya, the answer is clear. “When you see all the people that are creating content for everything, these are the people that should be in charge and influencing what happens."

Right now, that hope is as far from reality as the metaverse itself. Even as the technology becomes more accessible, the digital landscape remains dominated by big names and big bucks that determine its evolution. “We need to course-correct,” said Ovadya.

- Bring your projects to life with the best free video editing software

Steve is B2B Editor for Creative & Hardware at TechRadar Pro. He began in tech journalism reviewing photo editors and video editing software at Web User magazine, and covered technology news, features, and how-to guides. Today, he and his team of expert reviewers test out a range of creative software, hardware, and office furniture. Once upon a time, he wrote TV commercials and movie trailers. Relentless champion of the Oxford comma.