An ode to Intel’s 4004 processor: the one that started it all

A tech veteran ponders on the product that kickstarted Intel’s domination

1971 – what a year that was – and I'm afraid I can remember most of it. In November 1971, the Mariner 9 satellite orbited Mars, the album Led Zeppelin IV was released and Oman was granted independence from the United Kingdom. I met Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page in the 1970s – but that's a different story altogether.

And in 1971 Intel started advertising a chip called the 4004. I don't remember noticing that at the time but the semiconductor company has dominated my working life from 1987, until, er, now.

Intel historian Elizabeth Jones claims a lot for the introduction of the 4004. She says that we would not have smartphones, AI that recognises facial expressions, live mapping systems and the rest. She doesn't say that Intel failed spectacularly in the late 1990s to recognise that smartphones and tablets would come to overturn the hegemony of desktop and even notebook PCs.

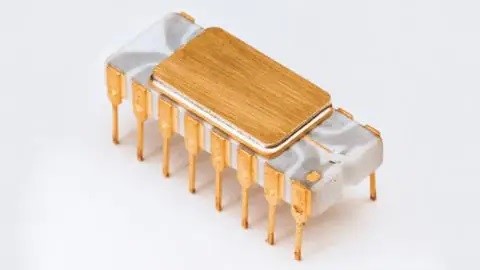

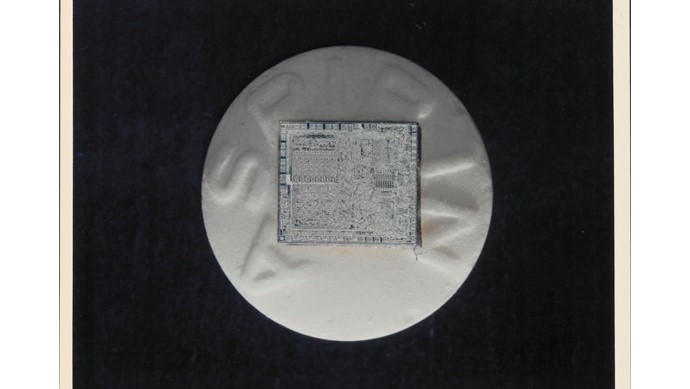

Originally, the 4004 was designed to be the engine for a Japanese company to produce a prototype calculator using 12 custom chips, but engineers Ted Hoff, Stan Mazor and Federico Faggin were able to produce four devices – including the 4004 – in November 1971. But it wasn't until five years later that Intel was able to draw on its ideas and really start to “shrink the die”.

Malcolm Penn, CEO of UK semiconductor analyst firm Future Horizons, told TechRadar which problems the 4004 overcame.

“The symbiotic combination of visionary IC system design and programmability gave birth to the world’s first general purpose microprocessor”, he said.

“An iconic ‘rock star’ design, it stands head and shoulders alongside the ubiquitous 7400, 702/09/41 and 1103 as pioneering revolutionary ICs (integrated circuits).”

Are you a pro? Subscribe to our newsletter

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

He said that by the end of the 1960s, a single MOS (metal oxide semiconductor) IC could contain 100 or more logic gates. That technology, however, was much slower than chips using TTL (transistor-transistor logic). The 4004 had 2,300 transistors. Contrast that with today's CPUs from Intel with around 100 billion transistors for Ponte Vecchio, the company’s most complex system-on-chip, released in August 2021.

“The symbiotic combination of visionary IC system design and programmability gave birth to the world’s first general purpose microprocessor”, said Penn. “Whilst its success in the marketplace was limited, quickly superseded by second and subsequent generation designs, it opened the floodgates for the microprocessor era.”

The story is a little more complicated than Intel suggests.

According to Ken Shirriff, a former programmer at Google and a historian of semiconductors, the 4004, created for Japanese calculator firm Busicom, had competitors including Mostek and Texas Instruments, who created calculators on a single chip.

But the genius of Intel and its engineers was that the 4004 could be used for general purpose computing. It came to develop better manufacturing processes for its range of microprocessors, predicted by Intel co-founder Gorden Moore to proclaim in 1965 that the number of transistors on a semiconductor will double every couple of years, while the price of chips will halve (ed: universally now known as Moore’s Law).

The successor to the 4004 would become the Intel 8080 chip, later leading to the 16-bit 8086, first adopted in the IBM PC. A myriad of other PC companies sprang up in the late 1970s to compete with Big Blue.

Shirriff said in a report in 2016 that he considered that the “honors for creating the first microprocessor depend on how you define the word. Some define a microprocessor as a CPU on a chip. Others say that all that's required is an arithmetic logic unit on a chip. Still others would allow these functions to be packaged in a few chips, which would effectively make up the microprocessor”.

There was no guarantee at the time that Intel and the x86 technology would come to dominate the microprocessor market, said Shirriff. There's more fascinating information on computer history on his blog. There are plenty of other factors which helped Intel deliver its success in the microprocessor market, including the leadership at the helm.

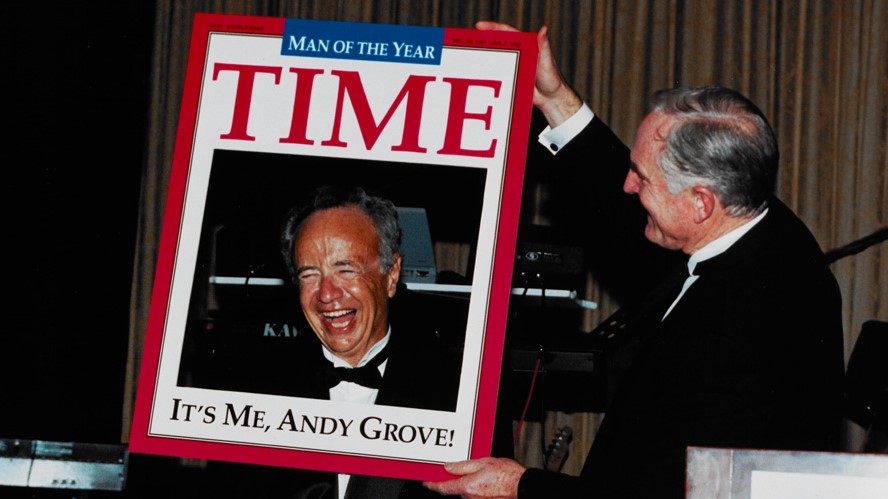

One important person in its success was the third employee of Intel and its third CEO, the late Andy Grove, a Hungarian refugee. He coined the phrase “Only the paranoid survive”, meaning that a company always had to keep its eyes on its competitors and avoid complacency. He expanded that principle into a book of the same name in 1996.

I met Grove a couple of times – an obviously driven individual, he welcomed plain speaking and the harder the questions, even from journalists, the better. He incorporated these principles into management styles in the corporation, demanding that employees use plain speaking to their bosses. The results – predictably – sometimes caused a lot of friction.

But Grove also realised that it wasn't enough just to have engineering excellence to succeed. Intel has a history of using very sophisticated and slick marketing to push its products and promote itself. Some wit even coined the word “marchitecture” to describe Intel's approach. It also employs a large team of public relations officers worldwide to inform and to fend off journalists' questions it doesn't necessarily want answered.

The marketing slogan “Intel Inside” and the accompanying refrain must have been heard by hundreds of million people.

Intel recently announced that it has no intentions to switch to a “fabless” model, where it would design chips manufactured by a third party. Instead, it intends to invest many billions in expanding its manufacturing capabilities. It has already started to build two fabs, with plans for a third fab too. CEO Pat Gelsinger – one of Andy Grove's protéges – wants the company to provide a third of semiconductor manufacturing worldwide.

Gelsinger obviously has faith in the future of x86 technology although Apple has moved away to designing its own microprocessors in the shape of M1 and its successors. Is it likely that this switch could mark the beginning of a change in direction in the microprocessor market? It's way too early to say the jury's out on that – the case hasn't even got to court. And Microsoft and Intel are joined at the hip in the x86 waltz.

The really big questions are for how much longer Moore's Law will be valid and whether quantum computing technologies will topple current microprocessor designs. If and when that happens it will be the end of the road for x86 technology.

We've also featured the best Intel processors

Mike Magee has written about tech since the 1980s, edited many titles and has written many many words in his lifetime. His speciality is news writing and he takes a keen interest in semiconductors. He co-founded The Register and founded The INQUIRER.