One year into Russia's war in Ukraine, "all is not quiet on the cyber front"

What does the Russia-Ukraine war mean for the future of cyberwarfare?

"Be afraid and expect the worst." This was the message coming from Russian hackers on January 14 last year. The text was shared in three languages (Ukrainian, Russian and Polish), and was posted after bringing down over 70 Ukrainian government websites and threatening to expose citizens' data.

The first Russian tanks crossed the border with Ukraine a month after marking the beginning of the war on February 24, 2022. However, the opening salvo was fired long before on the online front, setting up the role of the digital space in upcoming clashes.

Undeniably one of the most influential geopolitical events of the last few years, the war in Ukraine clearly shows how cyberspace has increasingly become a prolific battleground in modern times.

There was a huge rise in cyberattacks related to the conflict, for example, that brought citizens to increasingly download VPN services. At the same time, international hacktivist groups entered the game as well in support of Ukraine to launch a proper cyber war against Russia.

Now, a year on, how have these cyberattacks played out throughout the 12-month period? Have they really altered the course of the conflict? What's next for the future of cyberwarfare?

We are at War ! #Russia are you taking notice ? We do not forgive ! We are Legion ! We are united with #ukraineFebruary 25, 2022

Russia-Ukraine online conflict: an overview

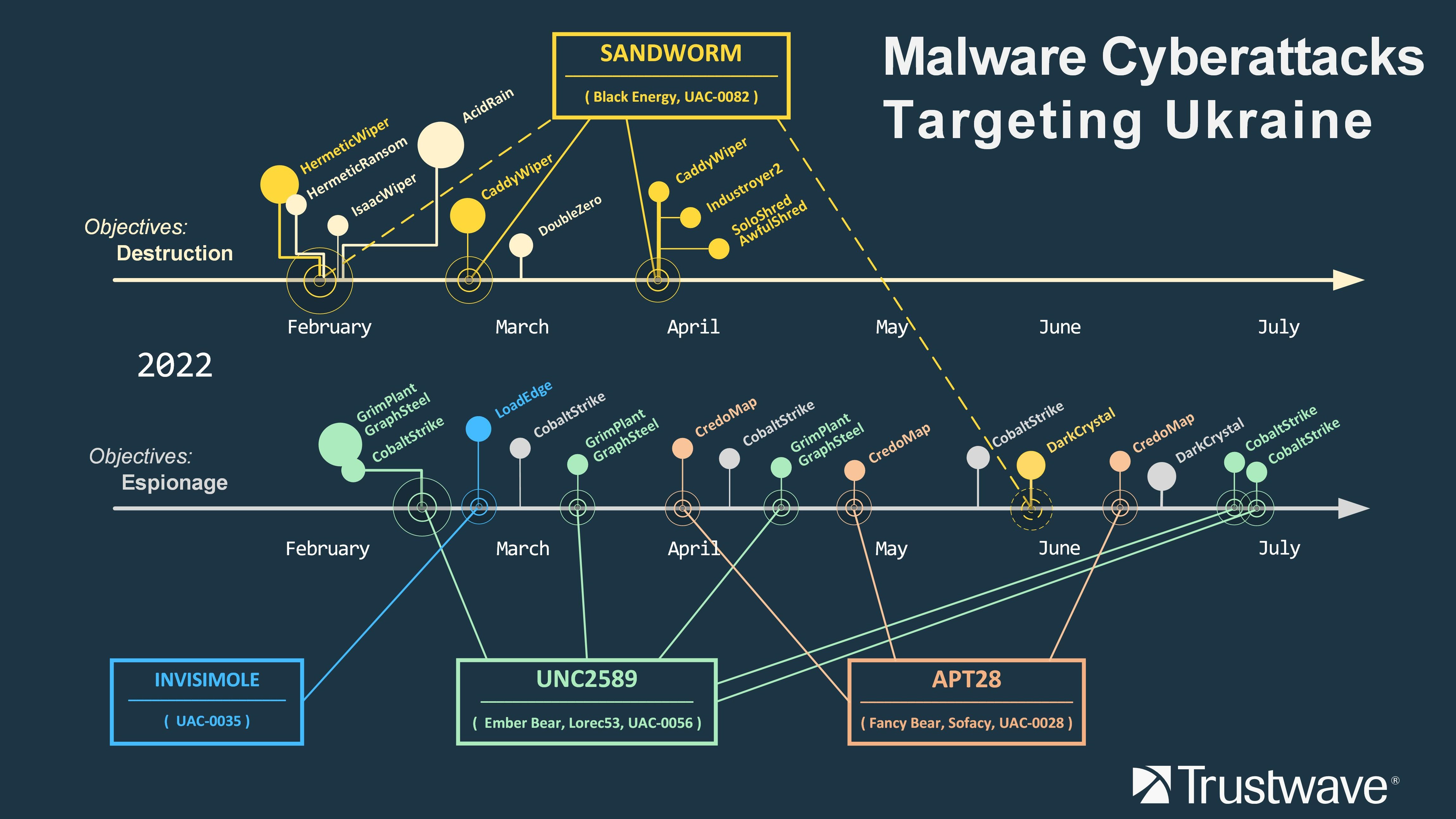

According to Google's Threat Analysis Group (TAG) and Mandiant's recent joint report, there was a 250% increase in Russian cyberattacks against Ukraine compared to two years before. The first four months of the war were especially active on this ground.

"The Russia-Ukraine cyber conflict may not be as visible as tanks and missiles, but only the post-mortem will tell us how much of a role they played," said Sam Curry, chief security officer at Cybereason.

Are you a pro? Subscribe to our newsletter

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

"The attacks are real, from wipers being passed to logistics and supply chains being slowed. In war, these things may not be flashy but when trains don't run and ammunition or gasoline doesn't arrive, it makes a huge difference."

The nature of the attacks would span from destructive operations to render key infrastructures inoperable to espionage activities, as well as the spread of misinformation online.

"There is also a quiet battle with real stakes being waged on the cyber front for control of the narrative on both sides," said Curry.

Malware, including as many as six different wiper strains, have been spread mainly via phishing campaigns and the exploitation of popular applications like VPN software.

According to cybersecurity threat intelligence researchers at Check Point, Russian weekly attacks against Ukraine were down 44% from October onwards compared to the first months into the conflict.

At the same time, there has been an increase of 9% of attacks carried out against the Kremlin. Outside Ukraine, NATO countries have been increasingly targeted with phishing attacks by pro-Russian threat actors.

"All is not quiet on the cyber front," said Curry.

A new era of cyberwarfare

The war in Ukraine might not be the first conflict where the online front has played its part, but it's certainly one of a kind as many people across the world got involved in such large-scale operations.

Western sources attribute most of the Russian attacks to GRU, the country's military intelligence service. Many notorious proxy groups stepped in as well, including the infamous Conti ransomware group, Gamaredon and Sandworm. Pro-Russian hacktivists from KillNet were also responsible for a series of "limited" successful DDoS attacks.

As much as happened offline, civilians were tangled up into this online war too. Wipers targeting their devices and everyday services aim to cause chaos in society by creating a spiral of psychological and financial pressure.

Despite the destruction provoked, experts from the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) believe that these attacks failed to bring a real value into the conflict.

"It may offend the cyber community to say it, but cyberattacks are overrated. While invaluable for espionage and crime, they are far from decisive in armed conflict," reads the CSIS report. "Ukraine was not the first cyber war nor was cyberattack particularly useful to the Russians. The Ukrainian defenders and their partners did a good job of reacting quickly to deflect Russian efforts to disrupt networks."

Ukraine had a long time, in fact, to build its defense against Russian cyber attacks as these began as early as 2014 - when the conflict around the annexation of Crimea first escalated.

President Zelensky could also count on the support of many NATO countries, especially Ukraine's Baltic friend Estonia.

Alongside this, the international hacktivist community mobilized as soon the first missiles flared up over Kyiv.

"Dozens of independent, or supposedly neutral, players in the non-state actor and cybercriminal ranks have taken sides in this conflict," said Curry.

Anonymous called hackers around the globe to fight the Kremlin on the net, launching a series of disruptive campaigns against Russian banks, major websites like Russian news outlet RT, and the country's Defense Ministry.

Even more extraordinary was a volunteer-led cyber defense group that gathered on Telegram to fight against Putin's actions. So-called IT Army, this unprecedented online militia surely created a model for the future of modern cyberwarfare - but not without controversy.

While other countries are getting ready to emulate such an approach, some critics believe that this may cause more harm than good.

That's because the line between legality and criminality might be blurred. Cyberspace is borderless, meaning that breaking the rules of international relationships can be very easy for volunteer hackers. This might result in other countries being dragged into war.

And, if as a defense tactic is working, the same approach is thought to be counterproductive on the offence front. As former NSA hacker Dave Aitel told Newsweek, "hacktivists make the battlefield very noisy."

What's more, some experts think that hacktivism is actually irrelevant to the course of the war. Researchers at CSIS noted, in fact, that efforts of pro-Ukraine groups against Russia have actually been exaggerated. This is mainly due to the challenges in successfully coordinating such a vast community of people.

What's next?

As we have seen, cyberwarfare is still far from matching up with the damage caused on the battlefield. Cybercriminals are able to strike with high speed and precision on countless targets simultaneously, but their destructive capabilities appear to still be limited.

Nevertheless, the Russia-Ukraine war is a source of knowledge for future efforts in this direction. The US and its allies can gain valuable lessons looking at Ukraine's successful defense architecture, for example.

At the same time, other authoritative countries like China and Iran could also learn from Russian failures.

"Just as stockpiles of shells and bullets get consumed, new research and development must produce new tools and weapons," said Curry.

As concludes Carnegie's report: "Modern wars will always feature cyber operations, but cyber operations won’t always be important to these wars. Rather, the scale of war appears inversely correlated with the strategic impact of cyber operations.

"If this correlation holds, cyberspace should probably not be seen as a “fifth domain” of warfare equivalent in stature to land, sea, air, and space."

Chiara is a multimedia journalist committed to covering stories to help promote the rights and denounce the abuses of the digital side of life – wherever cybersecurity, markets, and politics tangle up. She believes an open, uncensored, and private internet is a basic human need and wants to use her knowledge of VPNs to help readers take back control. She writes news, interviews, and analysis on data privacy, online censorship, digital rights, tech policies, and security software, with a special focus on VPNs, for TechRadar and TechRadar Pro. Got a story, tip-off, or something tech-interesting to say? Reach out to chiara.castro@futurenet.com