Why Messenger doesn’t need you to trust in Meta any longer

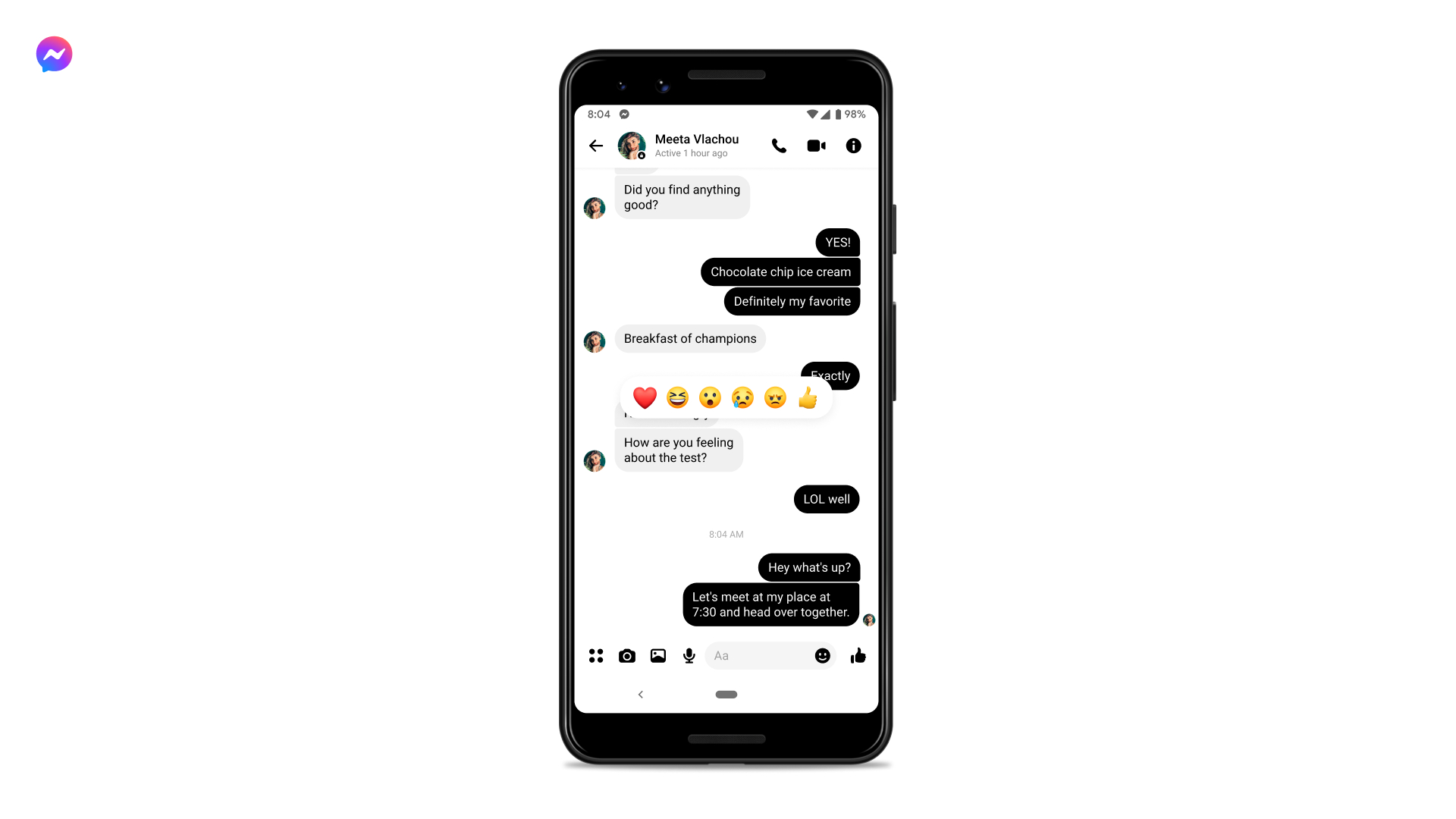

Messenger is on a path towards default end-to-end encryption

In early 2021, encrypted messaging platform WhatsApp made a costly blunder, publishing an update to its privacy policy that appeared to suggest users would have to share the content of their messages with Meta (née Facebook), its parent company.

In reality, the new terms applied only to interactions with businesses over WhatsApp, not conversations between friends and family, but the confusion was enough to send millions into the arms of rival services.

Ultimately, WhatsApp was able to clarify the nature of the policy update and there has been no material long-term effect on its popularity. However, the incident made two things clear: people are no longer willing to tolerate invasions of privacy and neither do they trust Meta with their data.

Alongside WhatsApp, Meta operates a second messaging service, called Messenger. The clearest difference is that WhatsApp lets anyone with a phone number exchange messages, whereas Messenger does the same for anyone with an internet connection.

But another significant disparity is that Messenger does not offer end-to-end encryption (E2EE) by default, which has invited questions over the years as to how Meta monitors communications over the platform.

The company has repeatedly denied that private messages are tapped as a source of personal data. But nonetheless, in a bid to dispel concerns and demonstrate its commitment to privacy, Messenger is now moving slowly towards default end-to-end encryption too.

One of the individuals tasked with overseeing this transition is Gail Kent, Director of Policy for Messenger, an expert in communications technology with a background in law enforcement.

Are you a pro? Subscribe to our newsletter

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

“Privacy is something that really matters to most people, and particularly more vulnerable groups,” she told TechRadar Pro. “Our aim is to create the safest private messaging app, with encryption as the cornerstone.”

Meta's privacy record

Unfortunately for Messenger, there are few companies in the world with a worse reputation than Meta with regards to data privacy. As much as the company may deny it, this is probably at least part of the reason it chose to rebrand in October last year.

The data privacy scandals that have orbited Facebook over the years are many and various, extending practically all the way back to its first years in operation.

In 2006, for example, Facebook found itself in hot water over an initiative called Beacon, whereby the details of users’ online purchases were shared automatically with their friends, no matter how personal.

A few years later, founder Mark Zuckerberg made headlines after declaring that privacy was no longer a “social norm”, a philosophy reflected in Facebook’s lax approach to the kinds of user data available to app developers at the time.

The company has also faced criticism over its willingness to deploy users as guinea pigs in scientific research. In 2010, Facebook allowed academics to experiment with how changes to the feed might affect voting patterns, and later, a separate study saw researchers target groups of users with different kinds of content to assess the lasting impact on mood.

And then there are the data breaches, of which there have been plenty. Most notoriously, it came to light in 2018 that Cambridge Analytica had exploited a loophole in a Facebook API to harvest data on circa 87 million users, which was subsequently used to target political advertising ahead of the 2016 Brexit referendum and US presidential election.

During our conversation, Kent acknowledged that Meta has “lost trust through things like Cambridge Analytica”, adding that “building up that trust again is really important”.

The suggestion was that Meta will seek to demonstrate over time that its leadership can be trusted to prioritize the best interest of users. However, the campaign to bring default E2EE to Messenger could also be read as an admission that restoring trust in the company is impossible by any but technological means.

The nature of end-to-end encryption is such that no third-party is able to access the content of messages (including Meta), because the decryption keys are stored on-device exclusively. Introducing E2EE to Messenger, then, will mean users won’t really need to trust in Meta at all; only the technology.

Messenger drives towards encryption

Although end-to-end encrypted chats have been available in Messenger since 2016, the formal drive towards default E2EE started three years ago with an open letter authored by Zuckerberg, entitled A Privacy-Focused Vision for Social Networking.

In the letter, Zuckerberg detailed his new perspective on the value of privacy and established a series of principles that would define the future development of the company’s communication platforms.

“Over the last 15 years, Facebook and Instagram have helped people connect with friends, communities, and interests in the digital equivalent of a town square. But people increasingly also want to connect privately in the digital equivalent of the living room,” he wrote.

“I believe the future of communication will increasingly shift to private, encrypted services where people can be confident what they say to each other stays secure and their messages and content won’t stick around forever. This is the future I hope we will help bring about.”

However, the campaign to deliver on these promises has not been straightforward and progress is incremental. As things stand, Messenger offers both vanishing messages and end-to-end encryption for chats and calls (called Secret Conversations), but only if users make the effort to opt in.

As Kent explained, one reason Messenger could not simply switch on end-to-end encryption overnight has to do with the significant technical hurdles standing in the way.

“WhatsApp sets the industry standard when it comes to encryption and protecting people’s data. What makes it more complicated [for Messenger] is that users have the same expectations of its encrypted service. They want the same reactions, stickers, watch together features etc. - and those are complicated to build for an encrypted app,” she told us.

Earlier this year, Messenger announced that GIFs and reactions are now available in Secret Conversations, but the team is still working to close the gap on WhatsApp from a features perspective.

Perhaps the greatest roadblock, though, is that Messenger has encountered significant opposition from governments, particularly in the UK, which claim the move towards E2EE will provide shelter for criminal activity.

Although Messenger is confident its plans will not be derailed, the team will need to establish new ways of managing the risk of harm, when scanning for child sexual abuse material (CSAM) and other violations of the platform is no longer a possibility.

“Users want a trusted space in which to communicate freely, but there’s more to it than just encryption; there are policy issues to do with safety too,” Kent explained. “And there is no monolithic type of harm, it comes in all kinds of forms.”

Faced with these complexities, Messenger is taking what Kent describes as a “holistic approach” based on three core tenets: “prevention, control and response”.

Under the first pillar, the platform is focusing on preventing bad-faith actors from establishing contact in the first place, especially where minors are involved. One strategy is to use AI to identify signals across all Meta platforms that might suggest two parties should not be in communication, and another is to make it harder to locate non-adult users via searches.

Secondly, Messenger is aiming to give users tighter control over who they receive messages from, as well as the facility to block senders with ease. And lastly, the platform has made a commitment to “responding with care” in the event of an incident, by making it simple for users to report abuses and acting decisively on all reports that come in.

“We don’t think privacy and safety are in conflict,” said Kent. “This prevention, control and response framework is the right one; it enables us to maximize the benefits of encryption to human rights, but also allows us to mitigate the secondary harms.”

Necessary and proportionate

On the issue of encryption, Messenger is being pulled in all directions at once; the platform is tasked with balancing the need to deliver greater privacy (without compromising on functionality), with the responsibility to shield users from harm and supply law enforcement with the data necessary to prosecute criminal activity.

Separately, there are new proposals under the Digital Markets Act (DMA) that mandate a level of interoperability between messaging apps with the goal of facilitating fair market competition, contributing another layer of complexity.

However, Kent is convinced a balance can be struck that will allow Meta to meet the expectations of users without neglecting the interests of secondary stakeholders and any potential new compliance obligations.

“We mustn’t think that all data is going away because of encryption, there will still be useful data available to law enforcement, including information from non-encrypted services, metadata and user reports,” she noted.

“My opinion is that companies like Meta should take a responsible approach to working with law enforcement with the data they have available. But necessary and proportionate is the rule.”

As Messenger gears up for the switch to default end-to-end encryption in 2023, the debate around the technology will rage on. But for the average user, especially the Meta-sceptic, it will be a date to circle in the calendar.

Joel Khalili is the News and Features Editor at TechRadar Pro, covering cybersecurity, data privacy, cloud, AI, blockchain, internet infrastructure, 5G, data storage and computing. He's responsible for curating our news content, as well as commissioning and producing features on the technologies that are transforming the way the world does business.