How to watch and photograph this week's Geminids meteor shower

Capture some stellar snaps of 2021's Geminids meteor shower

Have you ever seen a shooting star? How about two on the same evening? Or even sixty per hour, streaking through the heavens? This year’s Geminids meteor shower is going to be one of 2021's most spectacular astronomical events, but if you want to see it, or better yet, turn out a decent photograph of it, you’ll need a bit of kit and a bit of planning.

Ready to learn something? The Geminids are the dust of '3200 Phaethon', a 5km-wide chunk of rock trailing a field of astronomical debris through which Earth will pass between December 4th and 17th.

This will create a spectacular meteor shower that'll be visible from so many places that we’re expecting to see plenty of photographs. The Geminids are moving at a brisk 78,000mph, and will burn in the atmosphere at an altitude of 63 miles, causing streaks of light easily visible to the naked eye.

But how exactly should go about watching or photographing 2021's Geminids meteor shower? Luckily, we have all the answers, so you can get prepped for this week's big astronomical show, along with the Ursids later in December.

When are the Geminids and Ursids meteor showers?

The Geminids meteor shower is visible between the 4th and the 17th of December, with its peak arriving around the 14th. Depending on the weather where you are, it will definitely be worth heading out to watch the skies either side of that peak evening, though.

The good news is that the Geminids appear pretty much equally brightly, albeit at different times. If you’re in the Northern Hemisphere, grab a coat and settle in, because the Geminids will be fairly visible all night long, giving you plenty of time to wait for a gap in the weather.

Our friends in the Southern Hemisphere can catch a few hours’ sleep – peak meteoric activity will happen in the early hours. Set an alarm that sees you in prime position around 2am and you won’t be disappointed.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

In terms of what you’ll actually see, you can expect roughly one meteor per minute during the Geminid peak, although that’s not actually the number of meteors overall. In fact, the hourly rate of shooting stars will be nearer 100, even if your actual success rate is going to be quite a bit less.

Significantly less, perhaps, given the unfortunate timing of this year’s Geminid shower and its coincidence with the state of our more sedate astronomical neighbor, the good old Moon. This will be nearly full on the night of the 14th, and won’t set – in the Northern Hemisphere at least – until nearly 3am. The Moon reflects plenty of light, so it’s going to upset both your night vision and the exposures of any photographs you try to take. True diehards will set their alarms.

Don’t look now, though, because no sooner will the Geminids have gone on their way than the Ursids will make an appearance. The Ursids meteor shower isn’t going to be quite as special, but will begin on December 17th and peak on the night of the 22nd of December. The window here is much tighter, so there isn't much point going out either side of that peak evening – but if the weather doesn’t cooperate for the Geminids, the Ursids could make for a great also-ran prize.

Where are the Geminid and Ursids shooting stars?

A neat astronomical term for you to learn is 'radiant', which is the point in the sky a meteor appears to come from. The Geminids’ radiant is the Gemini constellation – that’s not actually where the meteors come from, but it’s a good place to start looking for them. It’s not the only place you should look, though, as the sky will be fairly alive with meteors all night.

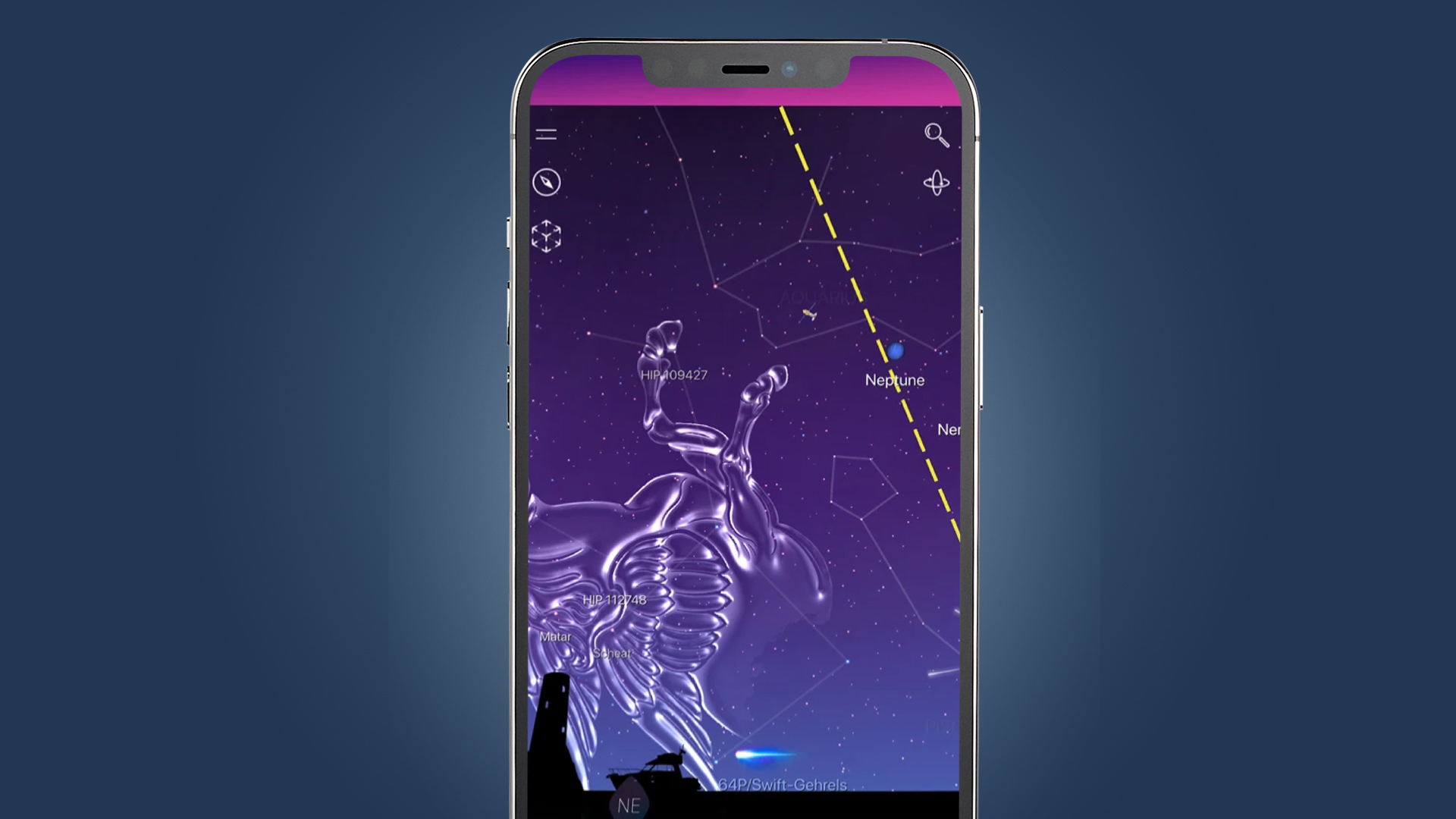

Don’t know where Gemini is or where to start looking? We’ve got you. The first thing to do is plunder your phone’s app store, because there are plenty of powerful apps out there to help. On the iPhone, we like the Night Sky X app (below, free with in-app purchases), while Android users should look at Star Walk 2 (free with in-app purchases, also available on iOS devices).

Both of these apps allow you to view the night sky in glorious Augmented Reality. Usefully, in the event that you still can’t tell the Big Dipper from Polaris, both allow you to type in the name of the constellation you’re looking for, then follow your phone’s on-screen prompts to find it. You’ll look a bit strange as you wheel around on the spot constellation-hunting, but it’s a great way of finding what you’re looking for.

Looking for the Ursids instead? The radiant of the Ursids is Ursa Minor, also known as the Little Bear.

What do I need and what I am looking for?

The main thing you need to look out for on your hunt for the Geminids is light pollution. The Moon will be your biggest problem, but there’s not much you can do about that. You can make sure you’re somewhere as dark as possible, which means away from urban centers, airports and the like.

The phenomenally useful Dark Sky Discovery website will show UK-dwellers dark sky areas near them, while those in the US can use the International Dark-Sky Association’s site to help.

You’ll need good weather as well – it’s no good prepping yourself to the gunwales only to be defeated by heavy cloud. We love the detail and accuracy of NetWeather.tv, which includes detail of cloud cover, temperature, precipitation and wind speed; the latter particularly useful for photographers on tripods.

A bit of cloud shouldn’t put you off, but if the forecast reckons more than 50% cover, you should start searching further afield. For best results, start looking at the weather for your intended location no more than a day or two in advance of your intended trip, as the forecast gets more accurate the shorter into the future it’s looking.

Of course, for those of us in the northern hemisphere, it’s likely to be cold. Once you’re at your location you can expect to be hanging around for a few hours, and the less you move, the colder you’ll get. The best thing you can do is make sure you have something to cover your head and a decent pair of gloves – ideally a woolly under-glove and then a heavy duty mitten on top. Layers are always king – go for something insulating underneath (merino wool is a staple), then layer over the top. The more layers you wear, the more heat from your body will be trapped, and the longer you’ll be able to endure low temperatures.

A warm drink is comforting but is no substitute for good quality clothes. Alcohol never works, partly because you’ll probably be driving and also because the warming effect you feel is literally skin-deep, opening up blood vessels near the surface, which makes you feel warmer, but actually decreases your core temperature. Coffee is great for keeping you awake but is a diuretic, so make sure you’ve got regular water to drink as well to avoid dehydration.

A torch will be useful, as anyone who’s ever tried to set a camera up in the dark will tell you. It’s tempting to take the brightest LED-powered light you can find, but this will have the unwelcome effect of ruining your night vision, which is why astrophotographers can be found poking around in near darkness with a puny red light strapped to their heads. Your eyes use rods and cones to turn light into useful information; cones are used for night vision and can primarily detect movement, and only in black and white. It takes about 20 minutes for them to start working properly, and red light causes your night vision to deteriorate more slowly than bright white light.

Excellent news for those in the Southern Hemisphere, where of course it’s summer. You rotters.

How do I photograph the Geminids and Ursids meteor showers?

The million dollar question. We can tell you with certainty that your cameraphone is going to struggle – if you can get it into manual mode, mount it on a tripod and allow it to reach for the stars in terms of its sensitivity (ISO). it might return a few decent looking images.

But a mirrorless or DSLR camera with a decent-size sensor (APS-C or better) is going to be best. Full-frame is the best possible option, as the larger the sensor, the better image quality is going to be at higher ISOs.

The setup

Meteor photography like snapping the Geminids tends to be what we astronomical wonks call 'wide field', which means instead of trying to tease out the details of distant constellations, we’re shooting ultra-wide angles that cram as much in as possible.

There are a few good arguments for that here – the wider your lens is, the longer your exposures can be, which means you’ll get more light onto your sensor, as well as increasing the amount of time that your camera will catch meteor streaks as they appear. A wide-angle lens also means a wider field of view, and therefore a greater chance of grabbing a decent frame of a meteor wherever it appears in the sky above you.

You’ll also want a tripod – if you’re going to buy one, opt for something sturdy (have a leaf through our guides to the best travel tripods and best tripods). Winter photography tends to be a bit windy and the better your tripod is, the steadier your images will be during long exposures. If you know your tripod is prone to getting jiggled in the breeze, set it up nice and low to the ground.

A spare battery won’t go amiss – cold weather is bad news for battery longevity, particularly when you’re shooting energy-intensive long exposures. If you don’t have a spare and your battery dies, try popping it in an internal pocket for a few minutes, which will often restore the cells enough to shoot a few more frames.

Finally, there is an argument for a star tracker here. Star trackers are motorized camera mounts, and sit between your camera and the tripod, and ever so slowly turn your camera at the same rate as the Earth’s rotation. That allows you to use theoretically unlimited exposure times, with knock-on affects in terms of which ISO and aperture you can choose.

Star trackers come in absolutely all shapes at sizes, prices start around the $300 / £300 mark for something that will work well with a full-frame DSLR or mirrorless camera with a pro wide-angle lens mounted to it. Equally, you don't necessarily need one to get great night sky images, as long as you follow these technique tips.

The settings

Astrophotography is a great way to learn how to use your camera’s manual mode. Because it will be so dark, your camera’s automatic metering system will be all at sea, so you won’t have a hope of getting a decent result. Instead, set your camera to its manual settings, open the aperture as wide as it will go, set an exposure time of around 15 seconds, an ISO in the region of 3200, and fire a tester image.

Use the image preview to refine your settings – if the stars above are too bright, a lower ISO is called for. If everything is under-exposed, try a slightly longer shutter speed. One thing to bear in mind here is the '500 rule', which says the longest exposure time you can use to photograph the stars before they start to smear across the frame because of the Earth’s rotation is 500 divided by your focal length.

So if you were shooting on a 50mm lens, your longest exposure time would be 10 seconds. Bear in mind that the '500 rule' only applies to full-frame cameras – if you’re shooting on an APS-C camera, you need to multiply your focal length by the amount your camera’s sensor magnifies it. So if your camera has a 1.6x sensor crop and you’re shooting that 50mm lens, you need to multiply 50 by 1.6, then divide 500 by the result (answer: 6.25s). The same goes for cameras with larger than full-frame sensors.

You’ll also want to get focus right. Setting your camera’s lens to its infinity setting will result in sharp images; the best approach is to use your camera’s live view mode to frame up your shot, then crop heavily into the live view image until the stars appear as fuzzy white blobs. Using manual focus, turn your lens’ focus ring until the stars are well defined. Don’t forget to make sure that pressing the shutter button on your camera doesn’t provoke another attempt at autofocus.

Finally, you might like to consider some strategic Photoshop. Even if you can stop the stars trailing in your images, ultra-long exposure times are to be discouraged in most digital photography as you could start to see hot pixels on your sensor, where a single pixel site overheats and appears in your image as a single bright dot. Instead, consider shooting lots and lots of long exposures, then blending them together to produce spectacular, multi-meteor effects.

- These are the world's best cameras for photography

Dave is a professional photographer whose work has appeared everywhere from National Geographic to the Guardian. Along the way he’s been commissioned to shoot zoo animals, luxury tech, the occasional car, countless headshots and the Northern Lights. As a videographer he’s filmed gorillas, talking heads, corporate events and the occasional penguin. He loves a good gadget but his favourite bit of kit (at the moment) is a Canon EOS T80 35mm film camera he picked up on eBay for £18.