How to find the International Space Station

Ready for some 21st century stargazing?

Have your heard? ISS in the stars...

Streaking across the sky after sunset can be seen one of humankind's greatest achievements: a permanent base in space, the International Space Station.

Okay, so it's not a Mars colony or a Lunar City, but the presence of six humans 250 miles above us is surely one of our greatest accomplishments of all.

Who's on board the ISS? Visit one of the best single-use websites around, How Many People Are In Space Right Now?, to find out.

It's easy to spot with the naked eye, and the sight of the ISS moving across the evening sky is the perfect way to kick-start some 21st century stargazing.

1. Understand its orbit

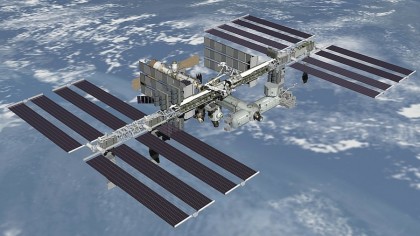

The ISS is unmistakable once you've seen it – it's at its brightest and best about an hour after the sun has dipped below the horizon but is still catching the solar panels of the orbiting laboratory – but its orbit is rather erratic from our point of view. Timing is everything.

The ISS orbits Earth 16 times in any 24-hour period, but since Earth is rotating from west to east and the ISS is orbiting diagonally from south-west to north-east, its path appears to shift north.

2. Know what to look for

If you've ever noticed a bright, white light streaming high up in a clear sky just after sunset, you've seen the ISS. It's often mistaken for an aeroplane, but there's no flashing light.

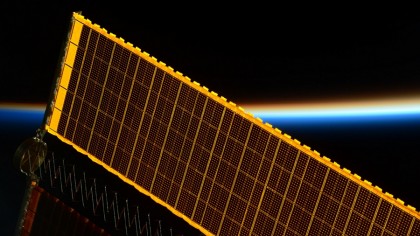

About the size of a football pitch, the ISS is mostly made up of giant solar panels, with four collections of four panels in each corner, and it's those panels reflecting sunlight that make the spacecraft visible from Earth around dawn and dusk.

It takes about four minutes to cross the sky, although depending on exactly when you see it the ISS can fade from view more quickly.

3. Know when it's passing

You can see the ISS every evening for about 10 days straight from a given location, but then you'll likely have to wait a couple of months for its return to the morning sky, then another couple of months to see it in the evening again.

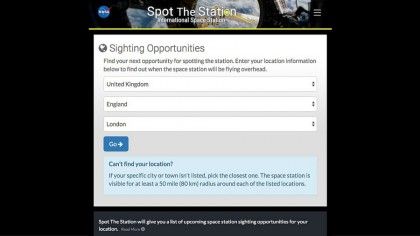

The easiest way to find out when the ISS will be passing over your location is to ask Nasa. Its awesome Spot The Station service asks you to select your country, state or region, and nearest city, and gives you a full breakdown of fly-bys in the next two weeks.

Even better, Spot The Station enables you to sign up for email alerts of 'good' sighting opportunities – so you won't get an alert every time it's in your vicinity, just those occasions when you're likely to see it more or less overhead.

4. Know when to look

You can't see the ISS in daylight, or in the dead of night – it's got to be near sunrise or sunset. The ISS is usually invisible at night because it's travelling through the Earth's shadow, so there's no sun to catch its solar panels, and in the day because it's swallowed up by the sun's ambient light.

If you see the ISS just after sunset (or just before sunrise), it will likely remain blazingly bright right across the sky. After a viewing near sunset, if you see it again 90 minutes later on its second pass (which is very often possible to witness), the sun will have sunk further, and its rays will only catch the solar panels until the ISS is perhaps third of the way across the night sky. As it disappears into Earth's shadow, the astronauts on board enter night for the 14th time in 24 hours.

5. Know where to look

The ISS is orbiting Earth the same way Earth rotates, so it appears in the west, crosses the sky, and sinks in the east. If it comes from the south-west, crosses the zenith (above your head) and disappears in the east, its next pass in 90 minutes will appear in the west and fade in the north-east.

Once you've seen it whizz from one horizon to the other in just a few minutes, its solar panels are unforgettably bright; you'll never fail to notice it next time it's overhead, even if you chance upon it.

6. Understand the sky

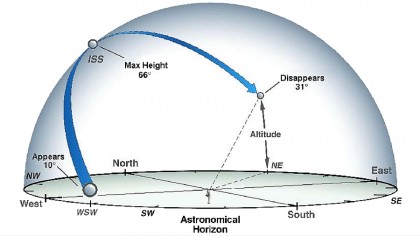

The sky is a dome, and it's measured in degrees. Gaze at the night sky and you can see 180 degrees; from the point above your head – the zenith – to the horizon, in any direction, is 90 degrees.

So when Spot The Station says, for example, 'Max Height: 66 degrees, Appears: WSW, Disappears NE' you can work out what this means – look west and it will appear, then it will climb to about two-thirds of the way up the sky, before disappearing in the north-east.

7. Download an app

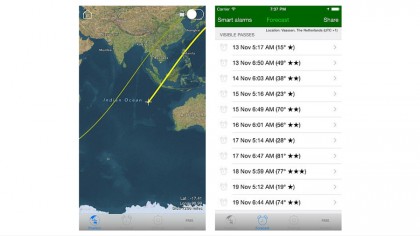

ISS Spotter turns seeing the ISS from a chance encounter into a regular, predictable event by plotting its progress on a world map. It also checks your location and produces a list of that month's exactly timed sightings (they usually come on three successive days every month or so), complete with optional alarm.

The fabulous stargazing app Sky Guide also does this, while other useful websites include Heavens Above, Astro Viewer, and ISS Tracker.

8. Get some binoculars

As the ISS is so small you won't be able to see Tim Peake looking out the window just by picking up a pair of binoculars. However, if you do use them you'll at least get to witness the unbelievable speed of the spacecraft.

Focus some binoculars (10 x 50s are ideal for stargazing), and train them just in front of where the ISS is, allowing it to race into the field of view… and quickly out again.

Following the ISS across the sky with the naked eye is easy, but it's only with binoculars that you can appreciate what 7.66 kilometers per second really looks like. Find a dark sky and the background of stars makes it look like it's going faster than a speeding bullet – which it is!

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),