All eyes on you: what is the future of public surveillance?

Seen. Recognised. Tracked.

Can you imagine trying to explain today’s privacy debate to your grandchildren?

I can. It’s awful. I’ll probably have to call it the 2010’s ‘Privacy Wars’ just to keep them on the rug. 2007 won’t be the year of the first iPhone for them, or the beginning of the age of the always-on-everythings that tracked grandpa and his friends around the world from space. They won’t understand what, if anything, about that was considered cause for alarm. Even when I explain what Ashley Madison was.

It will mean nothing to them that in September 2017, the daily number of daily connections to the anonymizing TOR network from the UK was somewhere between 70,000 and 80,000 per day. In 2014, the estimated value of the global Virtual Private Network (VPN) market was $45 billion - expected to grow to $70 billion by 2019. And if you plot the value of the Pound against the sort-of-but-not-quite-anonymous Bitcoin, a baby economist dies.

Privacy - both the protection and breaching thereof - is big business. But are we already further along than we think? What comes after that? What will we tell our grandchildren?

- Yes you can get a VPN free if you read our buying guide.

'Broadcasting your identity to the world'

“In terms of surveillance of your communications, then there’s all sorts of information: which websites you’ve been visiting, who you’ve been phoning - that kind of thing,” says Dr. Joss Wright, of the Oxford Internet Institute. “That [data] is not so much in the physical realm, but there is increasing crossover: the signals - or ‘track-ability’ - of devices by [way of] the fact that they are broadcasting data and connecting to information.

“Your mobile phone, because it connects from cell tower to cell tower, can be localised to within a couple of miles based just on when your mobile phone was connected to a particular tower. Then there are Wi-Fi connections. Your phone is constantly spewing out ‘seeking packets’, to see what Wi-Fi networks might be available… Your phone tends to send out the names of networks that you’ve connected to before, to see if they’re around.

"So, if your phone is connected to [your home network] it also tends to be broadcasting the name of that network as you’re walking around, and obviously that can be traced. [And] if your device’s Bluetooth is on, it will often be sending out pings looking for local devices around.

Are you a pro? Subscribe to our newsletter

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

“When your phone or your laptop is communicating over a wireless network or Bluetooth, it’s got a globally unique identifier - the MAC address. Which given that your phone tends to live on you almost 24 hours a day, means that you’ve got effectively a device that is broadcasting your identity to the world from a physical location, and any network that happens to be listening in a public space can locate that.”

Follow the money

After years of headlines, at least some of that will sound faintly familiar to most people. But putting your data about indiscriminately isn’t, in itself, a nefarious thing for your phone to be doing. What matters is who might be listening, and the businesses waking up to the idea that this could be an excellent new way to profile new customers.

“Where this could go looking forward, obviously a shopping centre or an advertiser is going to be very interested to know who is seeing their adverts,” Wright continues.

[Give people a] free service in order to show some relevant adverts to you [and] people tend to say, ‘Oh, yeah, that’s OK'.

“[Say] you walked past a [billboard]. Did you pause for a couple of seconds to look at the advert that was being displayed? If so, they can infer that you had some interest in that advert, and then potentially that… could feed into a profile about you. The next step up [could be]: if your phone is detected passing an advertising board, perhaps they might display an advert that was of interest to you as you walk past. This is where it could go on the corporate side.”

OK: a little unnerving, maybe. But not exactly Dystopian, in isolation. But the commercial interest in tracking consumers movements won’t be in isolation: it will be in harvesting as much information, on as many people, to build as accurate a profile of each, as possible. And as the prevalence of smart devices shows, we seem to be tacitly OK with that.

“People have very counter-intuitive and gut-instinct-level concerns with privacy,” says Wright. “If you let somebody know that Google is watching their communications in a relatively abstract sense - if you say, ‘to improve our service to you we will give you this free service in order to [show] some relevant adverts to you,’ people tend to say, ‘Oh, yeah, that’s OK.’

"If you reframe it as, ‘We’re going to scan through all of your private e-mails and build a profile on you so that we can target you more effectively,’ people start to be a bit more concerned. And then obviously when a privacy breach happens - as a hypothetical example: a recording of your home gets leaked from one of these devices which has been hacked, or your private photos are posted on BitTorrent - then obviously there’s a huge [sense of] privacy invasion.”

Big Data is watching

But if that’s what we’re willing to give away - tacitly or implicitly, in the case of new ‘assistants’ like Alexa or Google Home - what’s next for companies that want to track your movements and habits without resorting to your devices? People who leave the house ‘unplugged’ are still potential customers.

The UK famously nests the highest density of CCTV cameras on the planet. But the system is a mish-mash: different models from different eras using different video formats that can make finding and interpreting useful footage a nightmare. There is a pressing need for tools and companies than can knit this tangle of information together. SeeQuestor, recipient of the 2017 Frost and Sullivan Award for Technology and Innovation, has already had its system deployed in the UK and the US by law enforcement in investigations into cases up to and including murder.

“The first thing to say, for context, is that this is a post-event analytics tool,” says founder and chairman, Tristram Riley-Smith.

“We’re not talking about a real-time system. We’re typically dealing with a serious incident where there’s been a terrorist attack, a murder, a missing child or a rape, where it is [critical] for the police to go out and collect video data from all manner of different sources: old analogue machines working in shops, municipal cameras in streets, cameras on premises like parliament and video from people’s phones.”

Face detection, recognition and extraction

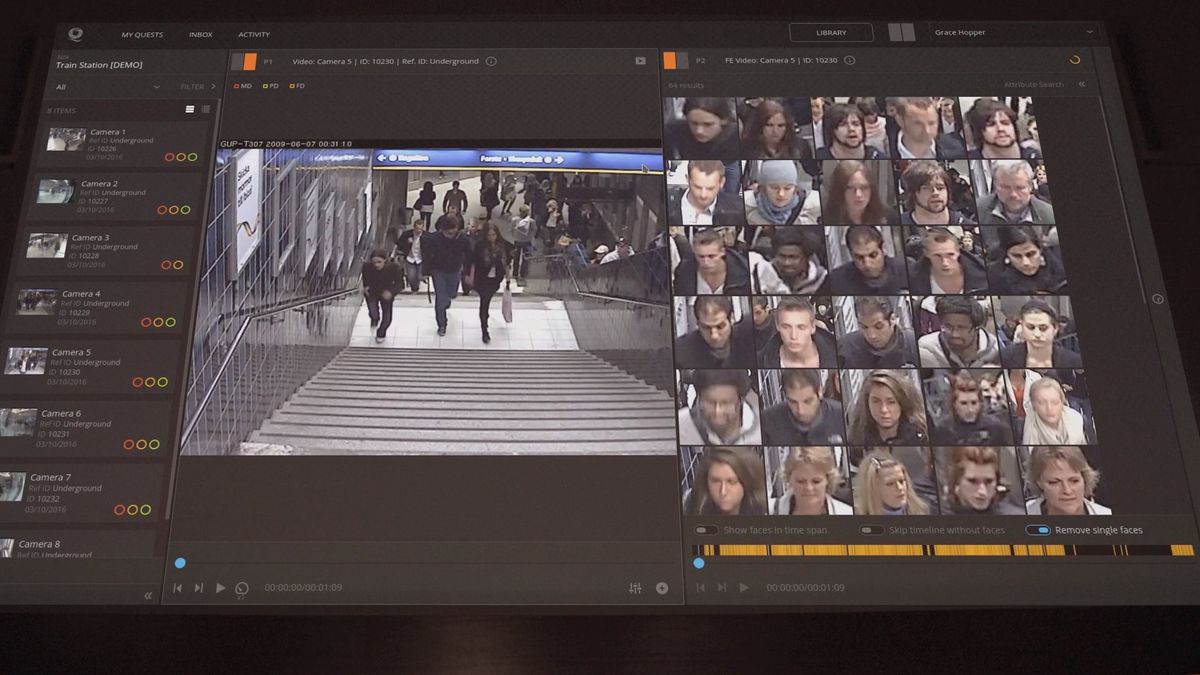

A demonstration of SeeQuestor’s system immediately brings to mind scenes from 2000’s-era police and terrorist TV dramas (with music to match). It’s not quite 24-levels of fantastical yet, but compared to the fogged-up film-grain CCTV we’re used to seeing on behind-the-scenes police documentaries, it’s strikingly closer to Hollywood than you might expect.

“There are four key tools,” Riley-Smith explains. “One is motion detection. The second is what we call face extraction or face detection, which I should absolutely emphasize is not the same as face recognition. The third is person detection - in other words where a box is being drawn round every figure within the video data. And the fourth, which really brings us to the unique, patent-protected part of the offering… is re-identification of those persons detected in the system.”

In other words, SeeQuestor’s system can recognise you, track you through a crowd with footage from one camera, then pick you out of the same crowd with another even if it temporarily loses sight of you. In the near future, the company’s plan is to give the system a more detailed suite of characteristics to track people with - hair length, glasses, clothing colour - a bit like digital game of Guess Who, but the character on the last unflipped tile gets arrested. And long-term, of course, the grail is a real-time system.

“We haven’t even started doing detailed work on the architecture of [real-time],” says Riley-Smith. “But we are starting to think how it could be deployed. I think we’ll be seeing there, in the early stages, that this is a capability that is deployed maybe on the edge of certain high-quality camera deployments, in locations where you have a single network - an obvious example would be an airport.”

SeeQuestor is acutely aware of the privacy implications of its system - its statement is front and centre on the company’s About page. But it’s easy to see how similar technologies, paired with the trail of data left behind by our smart devices in or out of the house could translate into huge financial incentives that - depending on the commercial operators’ scruples - could be either helpful or dangerously invasive.

To our grandchildren this will probably all be ancient history. But for us, now, that surveillance future is closer than we might realise.

- What is a VPN? Stay safe and out of sight online

Most Popular