An artificial mouse embryo has been created from stem cells

But it's unlikely to develop into a healthy foetus

One of the great miracles of nature is the moment when a fertilised egg turns into an embryo.

The process is something of a mystery - as it's too tiny to observe within the womb using ultrasound techniques, and scientists have never managed to recreate it outside the body. Until now.

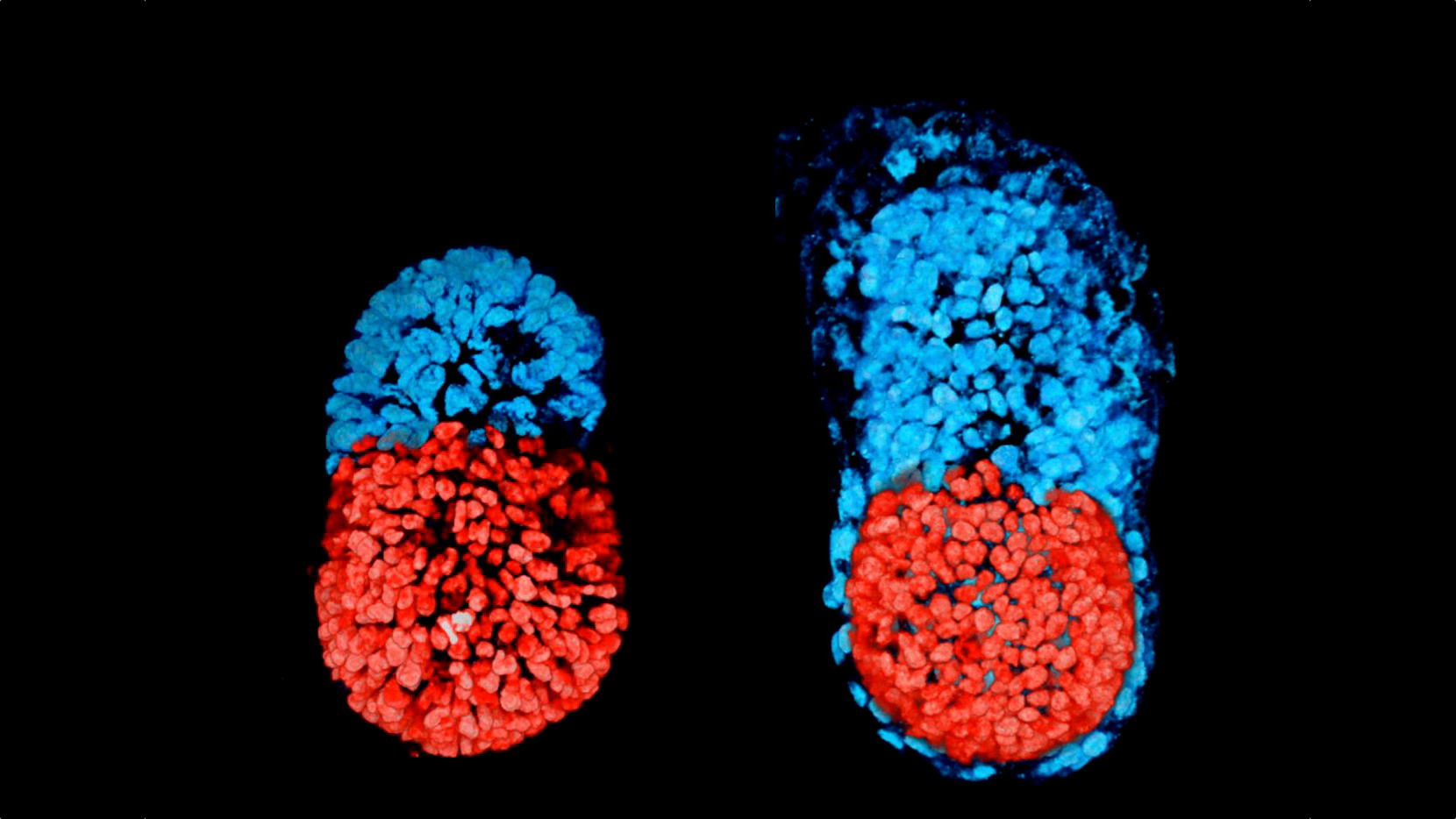

Researchers at the University of Cambridge have successfully created a structure resembling a mouse embryo using two types of stem cells and a 3D scaffold. The resulting artificial embryo closely resembles the real thing.

Behaves like an embryo

"Both the embryonic and extraembryonic cells start to talk to each other and become organised into a structure that looks like and behaves like an embryo," explained Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, who led the research. "It has anatomically correct regions that develop in the right place and at the right time."

Over seven days - about a third of a normal mouse pregnancy - the development of the artificial embryo followed the same pattern of development as a normally-developing embryo.

However, the researchers say that it's unlikely that the artificial version would be able to develop further into a healthy foetus. To do so, it would need a third type of stem cell which generates the yolk sac that nourishes the embryo and creates a network of blood vessels. The system has also not been optimised for correct placenta development.

Created and analysed

As well as shedding light on the "black box" of embryo formation, it's hoped that artificial human embryos will be able to be created and analysed, overcoming the shortage of human embryos available for research. That could eventually allow us to understand why human embryos so often fail to fully develop.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

"We think that it will be possible to mimic a lot of the developmental events occurring before 14 days using human embryonic and extraembryonic stem cells using a similar approach to our technique using mouse stem cells," said Zernicka-Goetz.

"We are very optimistic that this will allow us to study key events of this critical stage of human development without actually having to work on embryos. Knowing how development normally occurs will allow us to understand why it so often goes wrong."

The full details of the research were published in the journal Science.