Outdated music industry deserves no Govt help

Opinion: Why doesn't the government tell them to get stuffed?

General Motors, we're told, is 30 days from bankruptcy. That's sad for the people who depend on it for a living, of course, but it's hard to have much sympathy for a firm that's spent decades making cars that pollute the planet.

GM had the answer 13 years ago - it introduced the EV1 electric car in 1996 - but decided to concentrate on gas-guzzlers instead, discontinuing the EV1 in 1999 and crushing the lot in 2003.

Today's world doesn't want gas-guzzlers, and GM is desperately trying to catch up before it goes out of business.

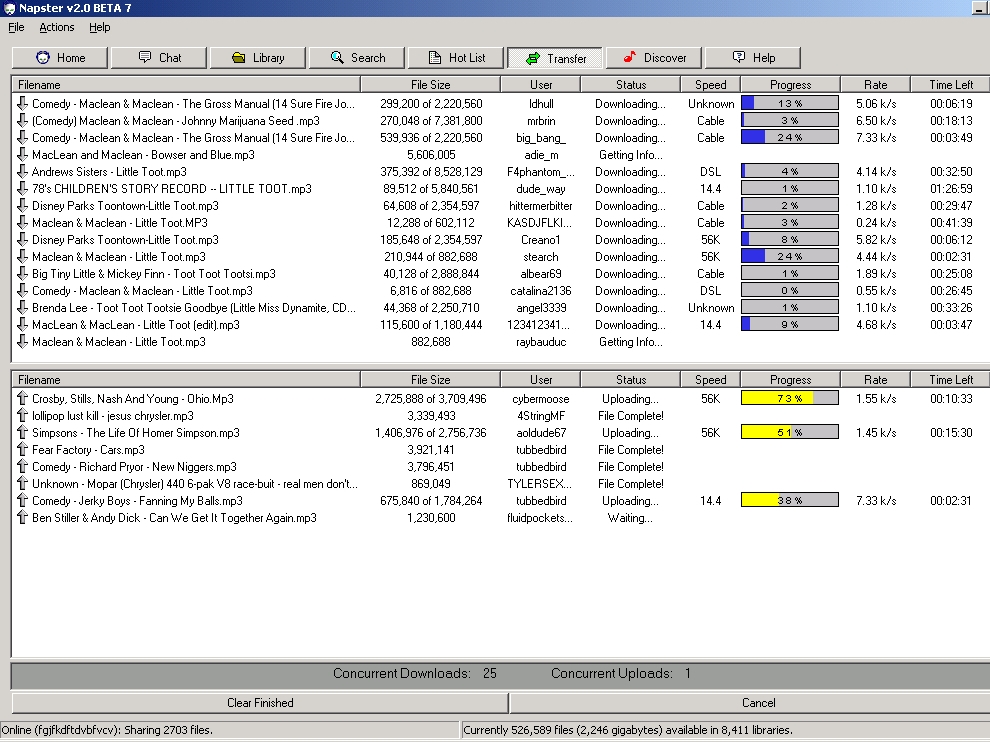

For gas-guzzlers, read CDs. When Napster came along in 1999, one big record company - BMG - wanted to find a way to harness the power of the internet. The other major record companies sued Napster - and eventually, sued BMG, too - starting an unwinnable war with dodgy downloads that continues to this day.

Now, like General Motors, the record companies are hurting - and like General Motors, they want the government to save them. GM wants cash; the record companies want ISPs to act as their policemen, while the Digital Britain report suggests a broadband tax to create a new organisation to fight piracy and find new and exciting ways for DRM to annoy us.

Why doesn't the government tell them to get stuffed?

Self-inflicted wounds

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

We don't doubt that the record companies are hurting, but many of the wounds are self-inflicted. Ten years after Napster they're still knocking down bright ideas, whether it's Pandora shutting its UK operation because of too-high licensing fees, Spotify having to cull its catalogue because of complex territorial agreements or Apple being pressured to increase the price of iTunes downloads despite digital being much, much cheaper to produce than physical products.

It's hard to have much sympathy. This is an industry that sues grannies and dead people and gets Google to zap your YouTube clip of the baby playing if Prince is on in the background. It's an industry that expects you to pay for a licence if other people can hear your radio. It's an industry whose artists, from the tax exiles of the 70s to bands today, do their very best to avoid paying tax.

It's an industry that's sued CD importing firms for daring to demonstrate that we were getting stuffed every time we paid £15 for a CD. It's an industry that penalised its best customers with terrible and short-lived legal music services that littered hard disks with unplayable, paid-for tracks when the servers shut down.

Government help? Where's the government help for travel agents, directory publishers, local newspapers, hard-core pornographers and other industries whose entire business models are disappearing thanks to online competition, legal or otherwise?

What's so special about music?

In it for the money

Andrew Dubber of New Music Strategies is an Arts and Humanities Research Council Knowledge Transfer Fellow in Online Music and Radio Innovation and a Senior Lecturer in the Music Industries at Birmingham City University, UK, and he specialises in telling the music industry the things it doesn't necessarily want to hear.

One of those things is that the record companies aren't the music industry. "The music industry is a vast, diverse ecology with lots of different people doing different stuff, but the record companies have managed to persuade the mainstream media to call them the music industry - which is a bit like the lions demanding to be called the zoo," he laughs.

Dubber, like us, isn't convinced that dodgy downloads are costing the billions of pounds the industry lobbyists claims. "How on earth do you come up with those figures, unless you say that the downturn in CD sales is so many billion pounds and the only thing that's caused it is the internet?" he asks.

The idea that every download is a lost sale gets short shrift, too. "It's like saying that every song you listen to on the radio is a lost sale. The stupid thing is that we've done all this already, fifty years ago. We went through it with radio, with the record companies refusing to provide music to radio stations... every time a new technology comes around they resist it strenuously, jump up and down about piracy, and then recalibrate their business and make money from it."

For Dubber, part of the problem is that the record companies have a very fixed idea of how the world should work - and that's the idea they're peddling to governments, with industry bodies suggesting that ISPs should kick people off the internet altogether if they share MP3s. "There's a presupposition with all of this, and it's really dodgy," he says. "It's the idea that whatever people want to do, whatever technologies are available and regardless of what the world is like, the music industry deserves to be given money. Everything starts from that premise: we provide all this value, we provide it in a way that we specify, and you must give us money... you're not allowed to hear music unless you give us money."

Writer, broadcaster, musician and kitchen gadget obsessive Carrie Marshall has been writing about tech since 1998, contributing sage advice and odd opinions to all kinds of magazines and websites as well as writing more than a dozen books. Her memoir, Carrie Kills A Man, is on sale now and her next book, about pop music, is out in 2025. She is the singer in Glaswegian rock band Unquiet Mind.