BioShock revisited: unpicking the complex, messy legacy of 2K's knockout franchise

How BioShock left its mark on the industry, for both good and bad

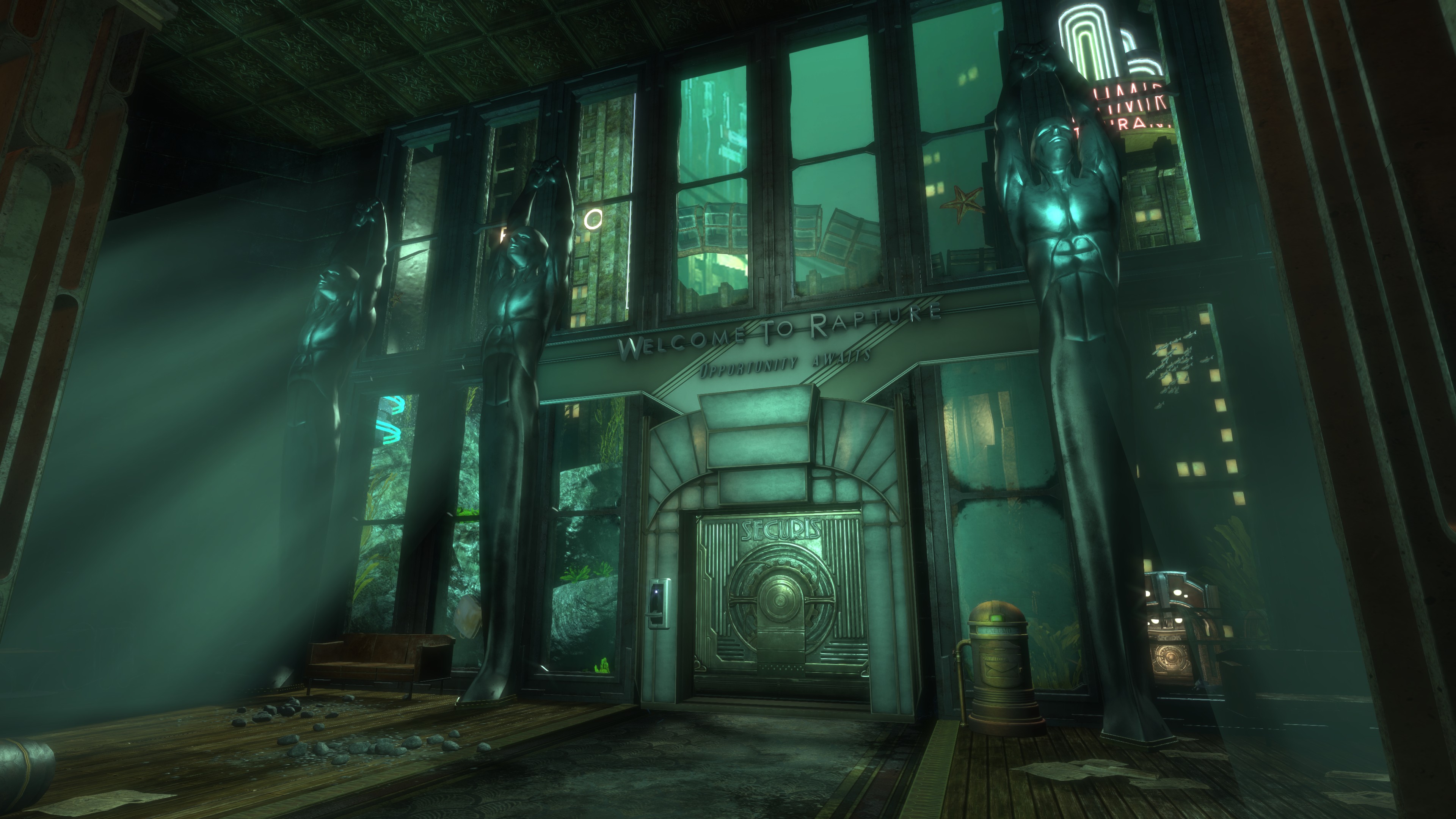

The “would you kindly?” twist in 2007's BioShock remains one of gaming's best: you can't see it coming and yet, when it happens, it makes perfect sense, and you look back on the story so far with a deeper understanding of Rapture's underwater world.

It’s the series’ most iconic sequence: one of those rare moments you still remember 12 years after you play it, and will probably remember in another 12 too. As Jonathan Chey, founder of developer Irrational, tells us, this moment isn’t quite "the soul of Bioshock", but it summed up what fans loved about their first trip to Rapture.

Plot twists can be cheap, and the stunning underwater environment that Irrational crafted would have been wasted on a lesser game; what made BioShock memorable was that it managed to surprise players while remaining completely coherent and believable. Everything about it, from the propagandist posters peeling off ornate walls to the audio logs hidden on shelves, felt connected.

“The world of BioShock isn’t just ‘hey, we came up with something crazy just to shock you’ – there’s a larger theme,” Chey says. “You can paint a very beautiful picture, but if it’s not interactive – if it doesn’t allow you to explore and manipulate and be affected by the environment – then it’s kind of like a funfair ride at that stage. What helped people connect [to BioShock] is that the world has meaning to the player, as well as being a pretty backdrop.”

A lot has changed since 2007. BioShock got a sequel and then a troubled third entry, Infinite, which had a long development plagued with conflict. This month, publisher 2K announced that a new studio, Cloud Chamber, is working on the next BioShock game. We thought it was the perfect excuse to revisit the series so far and ask: in our age where games, even exceptional ones, are so quickly forgotten, what exactly is the legacy of BioShock?

Shock to the system

BioShock felt unique when it came out in 2007, but the driving idea behind it was, in some ways, entirely derivative. The starting goal wasn’t to present players with moral dilemmas, but to simply build “another Shock game,” says Chey, referring to the System Shock series. Chey, along with Ken Levine and Robert Fermier, founded Irrational Games in 1997 after the trio left Thief developer Looking Glass Studios, and System Shock 2 was their debut. It's a PC classic, and one of the games credited with popularising the immersive sim genre. But parts of it were clunky, and despite critical acclaim it was never a huge commercial success.

For BioShock, Irrational – called 2K Boston by the time the game shipped – wanted to bring what it loved about System Shock 2 to a bigger audience. “Not just because we wanted to make some money out of it, but because we felt like most people in the gaming community aren’t aware of how cool this type of game is. So what can we do to mass market it?” Chey says. “Obviously, we weren’t talking about dumbing it down internally, but we were talking about making it more accessible.”

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Clearly, BioShock turned out to be more than just an extension of System Shock 2. The two games share some strengths – a blend of shooting and RPG elements, a complex relationship between player and antagonist, and environmental storytelling – but the things BioShock is most revered for only emerged later.

Its story gradually took shape as Levine drew inspiration from various sources: the life of John D. Rockefeller, the writing of George Orwell, and, perhaps most importantly, the objectivist philosophy of Ayn Rand, which came to define both the game’s apparent villain Andrew Ryan and the world of Rapture itself.

The team also landed on a role for the “Little Sisters”: young, genetically-altered girls who the player – upon coming across them – could either spare or harvest for ADAM, a resource that increased player power. It was a simplistic ethical dilemma, admits Jordan Thomas, a level designer on BioShock and the creative director of BioShock 2. But it still made players think.

“Most people didn’t say the moral choice system was revolutionary, but they said they felt something for the little sisters... they felt manipulated to think twice about the points [of ADAM] vs the narrative payoff,” he says. “Honestly, it’s kind of 101 in terms of any kind of ethical dilemma, and other games at the time had much more textured choices between the results you wanted to see, but few of those were built into the games systems-wide.”

It's this entangling of moral choices with theme, story, and mechanics that marked BioShock as special. It felt like the developers had thought carefully about every decision: the “manipulation” Thomas describes was a result of planning what the player would feel throughout their journey, leading up to the “would you kindly?” reveal.

The philosophical themes of BioShock games also gripped fans, and Chey points to the series’ close examination of complex themes as the biggest impact BioShock had on the industry at large. “In System Shock 2, I didn’t walk away with any kind of feeling that it had delivered me a message about the world. I wasn’t ruminating about the philosophical implications of AI. BioShock’s greatest innovation was the depth of its narrative, and the fact that it left you with things to ponder about the world.”

Philosophy's 'double-barreled shotgun'

What things? In the original BioShock it was, primarily, Ayn Rand’s objectivism, which rested on the assumption that a human’s “own happiness [is] the moral purpose of his life”. In BioShock 2, it was collectivism: prioritising groups over the individual. And in BioShock Infinite, a sprawling game, it was about cultism, quantum mechanics, destiny, and more. Thomas believes that what made BioShock stand out was how effectively it explored these ideas through its world design – turning philosophical arguments into “architecture” players could explore – without spoon-feeding ideas.

“What BioShock does brilliantly is allow you to physically explore the space described by a philosophy, and learn about it by osmosis, rather than being lectured,” he says. “Through sheer repetition and the fact that everywhere you turn, there was a lesson, whether it was visual or auditory, that achieves a sort of synthesis. I think people who knew nothing about objectivism got steeped in it to the extent that they could at least argue on the internet about it.”

Its profundity – a feeling, even if you didn’t engage with its philosophies, that it was about something – spilled over to other developers, argues Thomas: “The validation of the industry got thrust upon it,” he says, become an oft-cited example of “games as art”, with the “heavy mantle” that entails.

Those complex themes also spawned a tension, present throughout the series, between its nuanced ideas and the moment-to-moment action. It was a philosophy by way of a double-barreled shotgun.

“[It’s a] Jekyll and Hyde schism between the lofty themes that so many of the people working on the games want to discuss, and also the brutish, action vehicle that they must ride in," Thomas says. And looking back, that’s something that strikes me all the time about that era of video games, in trying to reach for something that speaks to the human condition, while also having to meet commercial demand.”

Most would agree that neither BioShock 2 nor Infinite lived up to the original, which is the one that garnered the best reviews among critics and frequently appears in lists of the greatest-ever games. In part, that’s just by virtue of being first: it was shiny and new, and fans hadn’t played anything quite like it before. To some extent, a sequel was almost always doomed to fail.

But it also points to structural issues with the development of both later games. For BioShock 2, as Thomas has previously described, that was both time and creative constraints. Now part of a different studio, 2K Marin, Thomas was given just two years to build the game, and told he had to compete with Gears of War and Call of Duty: a far cry from the Silent Hill-like game he wanted to create.

Development was a “heartbreaking series of returns to reality”, Thomas says. Initially, he poured his efforts into creating dreamscape versions of Rapture’s past, through which a Little Sister would discover her own history. But he eventually had to “step out of the way” for the version of the game higher-ups wanted, “with little dashes of the surrealism I so adore”.

Big ideas, little people

If he’d had the time, he would’ve wanted a deeper exploration of antagonist Sofia Lamb’s altruistic philosophy, he says. What he’s pleased with is that he got to tell the stories of the “little people”, echoing the fact that the game was made by a newer, smaller team. “We tried, we wanted to compete with big brother, but when we could not, we had this happy accident, which was that we moved the narrative to focus on the forgotten: the people of colour, the women of the era that were overlooked and disempowered, and then in the new power structure were prominent”.

He admits that he could’ve done more on this front – the game was called out by the Tropes vs Women in Video Games series for having female characters as “background decoration”, for example – but he sees it, at the very least, as a step in the right direction.

Infinite, in contrast, was hampered not by scope, but by its own ambition. As well as trying to act as an exclamation point on the series, it tried to tackle arguably the heaviest topics so far: racism, American exceptionalism, cults, and infinite worlds. The writers, Thomas included, became “really wrapped up” in the quantum mechanics of the world, perhaps to the detriment to the socio-political themes. Infinite didn’t have all that much to say about racism, for example, apart from the fact it existed.

“People tended to respond to it as either ‘this game is racist’, or ‘oh, these people are racist and this isn’t being portrayed with enough nuance. This is satire, but it doesn’t have the time to be deep satire.’ I understand those perspectives. Certainly, the team’s brain wasn’t turned off, it was just a function of time and energy and where it could fit amid the AAA gun show,” he says.

In trying to touch some many topics, the team gave less attention to each one individually. It was “a lot of ideas, all in competition”.

When we ask Thomas how he hopes players remember the BioShock series as a whole, he says he wants them to think of it like a “visit to a foreign country, where they were immersed in a place that challenged them, and that asked them, if not to learn a whole lot, at least to question the world around them, and what the real world around them is saying.

“That would be a wonderful start,” he says. “And then to allow their own ideas, whatever those may be, to mature in contrast to that immersive experience in a faraway place. I think the BioShock games, at best, are places where meaning can be explored, even if your mind doesn’t change, at least you had a chance to be exposed to another perspective, externalized and made dimensional, as opposed to just pushed at you.”

Walking on clouds

BioShock's legacy among fans, and the extent to which each player engaged with its ideas, is of course nebulous. What is perhaps more measurable is its impact on the development community. Some developers, such as Thomas, stuck with the series throughout; others’ involvement was more fleeting. Either way, though, each of them will have taken a part of BioShock with them.

Thomas, along with fellow BioShock developer Stephen Alexander, went on to found Question Games, which this year released horror-thriller The Blackout Club. Chey founded Blue Manchu, developer of Card Hunter and Void Bastards. Dishonored developer Arkane was called in as a support studio during BioShock 2: the studio’s co-creative director Sébastien Mitton helped build parts of Rapture before he built Dunwall.

Thomas also cites the big impact BioShock had on the indie space, saying that developers who had experienced the tension between BioShock’s story and mechanics responded by narrowing their focus on their own terms, easing that tension. It’s apparent in the work of Gone Home developer Fullbright, formed by a team who worked on the BioShock 2: Minerva’s Den DLC, for example.

“[BioShock] is still a bombastic action shooter, but it can be seminal in the sense that it inspired people to try harder, and to exceed what we managed to do,” Thomas says. “And I think there’s a role for games like that. You can be deeply critical of all three games, but I do think it asked people: ‘Hey, could we do a little more?’ I’m glad to see the industry get a little bit more interested in what their games are saying.”

In that way, perhaps we shouldn’t think of BioShock as a huge monument, towering from the sea, but – as Thomas puts it – as a series of “stepping stones” for others to use. With any luck, Cloud Chamber will tread on those stones – and follow a path to a new, exciting land.

- Hungry for quality titles? Check out the very best Xbox One games and best PS4 games