Scientific research has always been an expensive endeavour, and one that can often be difficult to justify. Research teams first have to reason away the cost of retaining large numbers of staff, including engineers, technicians and management. They also have vast expenses associated with laboratory costs, equipment, computer hardware and the huge amount of electricity required to run the above.

This can be hard enough in private industry, where the results are justifiable in terms of concrete output (products or services). But with scientific research the output may be nothing more than abstract knowledge, and alongside that there's always the danger that years of research will yield no results at all.

In order for these projects to keep going, they need to establish cost savings wherever possible. Unfortunately, it's difficult to source these savings without sacrificing the productivity of a team or the validity of the results.

If an organisation cuts staff, the research will take far longer, ultimately costing more; if it cuts equipment, the quality of work and output will suffer, something that isn't an option in such a precise field.

So where, then, are researchers to make these savings in a world where every penny spent is scrutinised and needs to be justified?

A big idea

A bright spark of inspiration from one individual can make a vast difference for thousands. In 1989, when Sir Tim Berners-Lee wrote a proposal for what would eventually become the World Wide Web, the ingenuity of one man changed the face of the world as we know it.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Berners-Lee was at the time working for CERN in Geneva, and the web was born of the concept of scientific collaboration. It seems appropriate, then, that the man who has invented what could be the potential saviour of the scientific community with one big idea cites the internet itself as one of the roots of his creation.

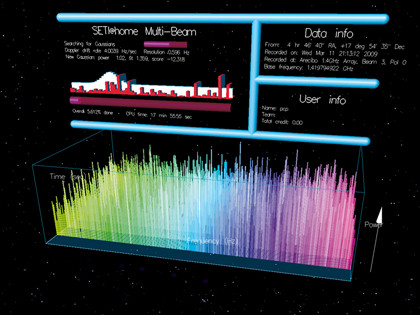

Dr David P. Anderson is a research scientist in the Space Sciences Lab at the University of California, Berkeley. He has headed the SETI@home project since 1997. SETI (or the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence) concerns itself with listening to the deep universe for some signature of life.

The SETI@ home project utilises the power of connected home computers to perform calculations and analysis of captured data on behalf of interested researchers. SETI@home was a pioneering endeavour because it was one of the first volunteer computing projects.

While it attracted much attention, it was limited in terms of some functionality, and there have been instances of users falsifying data in order to appear more prolific in the field.

But there was an upside: Dr Anderson began work on the successor to the original SETI@home software (now referred to as 'SETI@home Classic') in 2002, and as a result BOINC (the Berkeley Open Infrastructure for Network Computing) was born.

"BOINC is trying to create a system in which thousands of scientists compete for computing resources by publicising their research. Computer owners can then make careful, informed decisions about how to target their donation of resources," Dr Anderson told us.

There are over 35 separate research projects currently signed up to utilise BOINC in their computations. Dr Anderson has some pretty specific and ambitious goals for the project:

"The goals are [that] huge amounts of computing power – potentially all the computers in the world – are made available to scientific research. Scientists who are doing better research get more computing power, where better is defined by the public. The public gets interested in and excited about current scientific research, and learns about scientific method and the importance of scepticism and logic."

The concept of the public deciding what research is more important and which deserves more focus is an interesting one, and to an extent is already happening in the BOINC community.