From the introduction of the X-ray to the latest genetic-mapping devices, medicinal and technological advancements have always gone hand in hand.

Many of the everyday PC and general health technologies we take for granted are the direct by-product of technologies initially developed for the health professions.

But specialist clinics and hospitals are no longer the only places where such technologies reside.

From self-diagnosis websites to advanced insulin trackers, there is a mass of health-related technologies at our disposal. It pays to keep your wits about you, though; hustlers are keen to cash in on this sensitive field.

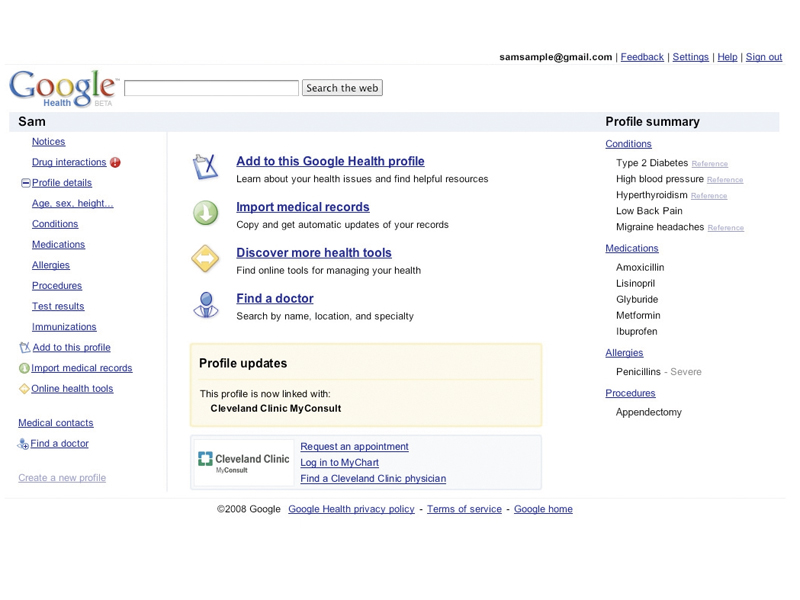

March 2007 saw the launch of Google Health, a unique service that aims to allow users to take control of their medical records while at the same time promoting the benefits of a healthy lifestyle and improving the well-being of its users.

Though critics hammered Google for its blasé approach to personal health data, its intentions at least appear genuine and munificent. There's no universal health care system in the US; no NHS to serve up standard treatment and be the butt of stand-up comedians' jokes. Google's attempt to de-privatise health records was seen by some as a benevolent gesture intended to make a genuine difference – much as its ongoing digital Library Project is intended to help keep the world's books alive.

We organise our daily lives through our PCs. Think about it: chances are you arrange meetings via email and Twitter, plan driving routes and directions through Google Maps and even manage your personal finance online. So, Google asked, why shouldn't the most important aspect of our lives – our health and wellbeing – be as freely and easily managed?

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

It's a question that many websites are asking, from dieting sites to online weight trackers and communities built around specific diseases and conditions. Google Health puts users in charge of their own medical documents. Full medical records, a complete prescription history and appointment and procedure information can all be imported into one place thanks to a partnership with the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS).

Google says its intentions are solicitous, and it has even drawn up a Health Advisory Council staffed with leading US health professionals and specialists. But just how secure the medical records are and what critics have termed the 'bite-back clause' in Google Health's Privacy Policy actually means remains to be seen.

According to its Terms of Service, Google Health doesn't actually qualify as a covered entity under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in the United States. Critics argue that the terms of the privacy laws set out under the Act cannot therefore apply to Google, and so renders Google Health unaccountable and open to abuse – accidental or otherwise.

In the UK, NHS Direct offers a service not entirely dissimilar to Google Health, minus the access to medical records. As the benefactor of a £16million investment drive, both the phone line and website have been a huge success for users and practitioners alike. For the patient, NHS Direct offers a simple question-and-answer progression through to diagnosis via its self-help guide. Symptoms that prove more serious are identified and a directory of local pharmacies and health services is also available.

The upshot is that common, minor complaints can be self-diagnosed and treated with a visit to the pharmacy while more serious symptoms will produce a page telling the user to get themselves to hospital. The theory is that only the most serious cases will then turn up in the GP's waiting room.

Regardless of intention or privacy concerns, services like Google Health and NHS Direct demonstrate a shift in the general public's view of self-diagnosis – and in particular, how acceptable and reliable it is. If we think that something's wrong, we now have new ways and means to speculate what the problem is. That's not always a good thing, however.