Back at the lab

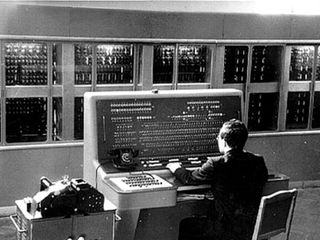

Meanwhile, back at Secret Laboratory Number One, Lebedev's team were creating the BESM-2 computer, which was their first system to go into full production.

According to the Russian Virtual Computer Museum, Lebedev's team had now swollen to 150, and they were even able to export a BESM-2 to China. By the 1960s, the Soviet military had truly woken up to the computer's potential for planning, logistics, and battlefield simulation. They demanded even more number-crunching power.

SECRET WAR: The BESM-2 was an impressive machine, but it used technology that was stolen from IBM

In response, Lebedev made the first Soviet supercomputer, BESM-6, in 1967. Running at an impressive 10MHz to speed execution, the BESM-6 used cache memory to store frequently used instructions and could work on processing up to 14 instructions at once. Lebedev called this the 'principle of water pipe' – what we now call instruction pipelining. However, much of the technology used in the BESM-6 wasn't original. It was stolen from IBM.

In the 1960s, computer scientists were ordered to abandon trying to surpass Western technology from scratch. Instead, they were to simply copy whatever IBM did.

Stealing to compete

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

And so, with a little help from the KGB, 1968 saw the start of a project to, shall we say, 'clone' the IBM System/360. This classic, powerful and immensely popular machine helped put man on the moon.

Officially, the initial design of the Russian version of the system came from the Moscow Scientific Research Centre for Electronic Computer Machinery, but the plans for it – and even pieces of hardware to make it work – secretly found their way from the West.

The Russian System/360 clone was called the ES EVM, and it soon became widely available in Russia. In 1972, the year that the ES EVM was released, Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev virtually admitted what was going on when he told a meeting of officials, "We communists have to string along with the capitalists for a while. We need their credits, their agriculture and their technology."

Theft quickly became the principal way that Russian computing kept pace with the West. In 1975, production began of a clone of the influential DEC PDP-11/40 minicomputer. Called the SM-4, it featured multiple video terminals and twin magnetic tape units – just like the real thing. The SM-4 so faithfully reproduced the original hardware that it even ran Unix, enabling it to run a wide range of stolen applications.

The successor to the SM-4 was the SM-1420. A cloned version of the DEC PDP-11/34+, it was produced in large numbers across the Soviet Union. The standard machine had 256kb of RAM, two 2.5MB removable disc packs, two magnetic tape drives and the ability to handle several video terminals. Predictably, the mid-1980s saw the first cloned Russian IBM PC, called the ES PEVM. It ran DOS and early versions of Windows.

LOOK-A-LIKE: The ES PEVM was a Russian copy of the IBM PC that could run DOS and versions of Windows

However, by now the West was onto the Soviets' little game. Game Over According to the book At the Abyss: An Insider's History of the Cold War by Thomas Reed – who at the time was a member of President Ronald Reagan's National Security Council – France shared vital intelligence with the US about Russia's technology stealing in 1981.

The French had recruited a KGB agent who was responsible for evaluating Western technology. Named 'Farewell' by his handlers, the agent had access to the KGB's Technology Directorate, which was stealing Western technology to study and copy. France revealed just how far the KGB had penetrated Western labs, companies and government agencies. Crucially, it also revealed the Directorate's technology wish list of things to obtain.

Now that the West knew about what was happening, what should they do about it? Reagan asked Bill Casey, his Director of Central Intelligence, for ideas. The plan he hatched allowed the KGB to steal whatever it liked – after certain subtle modifications had been made. From this point on, stolen microprocessors would for some reason spontaneously fail months or even years after deployment.

Stolen operating systems and applications contained time-delayed bugs that would make vital computers malfunction after months of perfect service. US intelligence also allowed the Soviets to steal faked 'secrets' about stealth and space defence technologies in an attempt to have them incorporated pointlessly into military projects.

In the early 1980s, the Russians were constructing a trans-Siberian oil pipeline, and needed an automated system to properly manage it. Softening attitudes allowed them to legitimately purchase older models of computers on the open market. They then approached the American authorities for permission to buy the necessary software. When the US refused, the KGB stole the application.

However, the software they stole had been doctored to go haywire after a while. It would open valves unexpectedly and set pressures too high for the pipeline's welds. When the explosion came, US seismologists measured the blast at three kilotons.

According to Reed's book, the Soviets were now unsure which of their key systems they could trust. During 1984 and 1985, the US consolidated their position by arresting and expelling large numbers of suspected KGB agents, effectively stemming the flow of technology and intelligence.

With domestic computers seriously underpowered, stolen Western technology randomly poisoned and President Reagan announcing his ambitious 'Star Wars' missile defence shield, the USSR now faced uncertainty as a second-class superpower.

With the country's infrastructure falling into disarray, people were beginning to voice dissent, as were politicians such as Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin. The USSR was starting to disintegrate – and decades of stealing Western technology instead of growing a native Soviet computing industry was partly responsible.

Most Popular