Could China’s plans for space exploration see it challenge NASA?

Red planets?

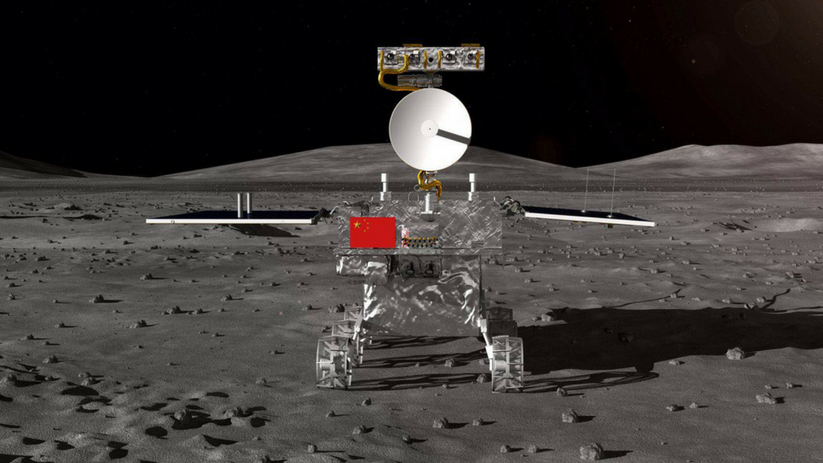

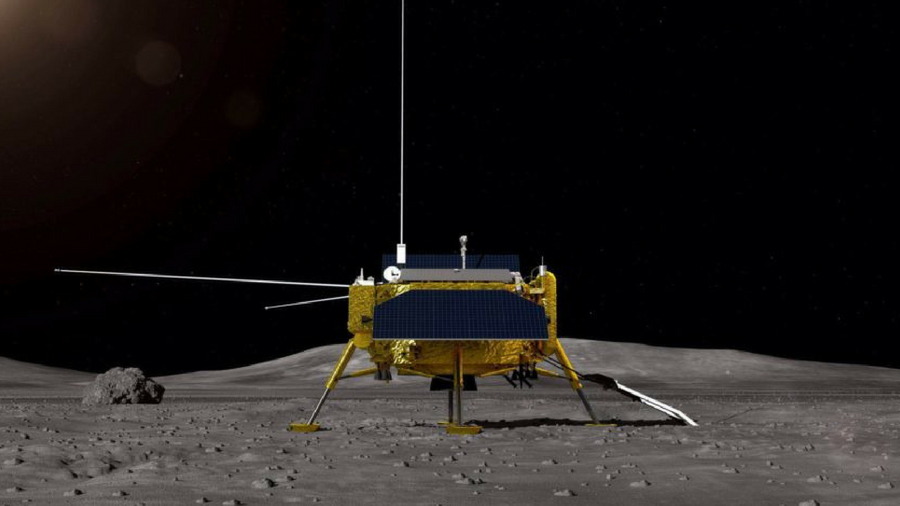

Main image: The Chang’e-4 will land on the Moon’s unexplored far side in December 2018. Credit: CNSA/CAS

In December of this year CNSA, the Chinese space agency, will attempt to accomplish something no other space agency has attempted: land a probe on the Moon’s far side. It’s the latest salvo in a slow but sure effort by China to become a major space power, which also includes plans for an orbiting space station, more powerful rockets, a Moon base, and even a mission to Mars.

Don’t think China is a major space power yet? For now, it’s had only sporadic success, but China could well be on the road to becoming just as important as NASA.

The Chang’e-4 mission

CNSA will attempt to land its Chang’e-4 on the far side of the Moon, but we're not talking about the dark side of the Moon here – there’s no such place. The Moon is tidally locked to Earth, so rotates only once during its 29-day orbit. That means we see only one side of the Moon, but the other is illuminated by the Sun just as much. However, the far side has never been landed on. A completely robotic mission, Chang’e-4 will attempt to land in the Moon’s Von Karman Crater, an impact crater in the southern hemisphere of the Moon’s far side.

“It’s a daring plan,” says Brian Harvey, space analyst and author of China in Space: The Great Leap Forward. “If it succeeds, and I would put the chance at 50-50, then China will have done something spectacularly different to the other space powers. There’s a lot of risk involved.”

The Chang'e-4 mission has actually already begun. One problem with the proposed landing is that it's impossible to send radio signals directly back to Earth from the far side of the moon, so in May of this year the CNSA launched a satellite that was successfully put into orbit beyond the Moon where it has a line of sight to Earth, so it can relay radio signals to and from the lander. It will also stream the landing live on TV around the world.

The Chang’e-5 mission

However, China has much bigger plans. Next year it intends to fly a ‘sample return’ mission to the Moon, using the same system employed by NASA during its Apollo mission to return lunar rocks to Earth. “The lunar module will fly up to lunar orbit and dock with the command module and return to Earth,” says Harvey. “That means it can bring back a bigger sample and it can also land anywhere on the Moon that it wishes.”

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

The principal target is Mons Rümker in the very northwest of the Moon. If it succeeds than China will have its own lunar rock, becoming only the third country to have any after the US and Russia.

China’s Long March 9 rocket

A lot will depend on China’s rocket program. A malfunction with its Long March 5 rocket led to an explosion in July 2017, but China has plans for a much more awesome, capable, super-heavy lift rocket called Long March 9 (LM9). Slated to begin flying in 2028, LM9 will be a beast.

“The payload the LM9 could take to the Moon is about 50 metric tonnes,” says Harvey. “The Saturn V was 40 metric tonnes, so we’re looking at something that is slightly bigger.” The Saturn V was used by NASA in the Apollo program in the 1960s and 1970s.

China’s plans for a Moon base and Mars

There are also plans to put astronauts on the lunar surface. “The first manned lunar landing is intended for 2030, but it’s not yet an approved government project,” says Harvey, adding that it’s important to make distinctions between what Chinese scientists would like to happen – a lunar landing in 2030, a lunar base in 2040, and a Mars landing in 2050 – and what is approved by the Chinese government.

“The first Chinese manned lunar expedition might not stay for very long – perhaps only a few days or a week – but China has no intention beyond that of doing Apollo-style out-and-back expeditions of three or four days,” says Harvey. He thinks they will quickly move to building a settlement on the lunar surface, possibly using a combination of rigid, inflatable and 3D-constructed modules for habitation, laboratory and support, and tunnels between each. Initial plans presented in 2017 envisioned space for between three and six astronauts.

China’s next space station

China’s first space station, Tiangong-1, burned up in the Earth’s atmosphere in April 2018, but it has plans to launch another. Harvey explains: “The first module of its manned space station, the Tianhe, will launch next year, with two more scientific modules to follow, and then will begin a pattern of manned launches, with China sending up three astronauts every six months.”

China’s astronauts are banned by the US from visiting the ISS. However, there’s a reasonable chance that China’s space station will effectively become the ‘new’ ISS. “The ISS may not be there after 2024, and the Chinese space station will go on flying well into the 2030s,” says Harvey.

After all, Tianhe is not a top-secret, China-only project; European astronauts Samantha Cristoforetti and Matthias Maurer have already trained in China for a flight there. However, to compare Tianhe with the ISS would be foolish; it will be much more like MIR, the rudimentary Russian space station of the 1980s and 1990s.

Is China’s space program essentially military?

The Chinese space program is often painted by the media in the US as essentially military by nature. “I see no evidence of that,” says Harvey, who insists that the problem with the US-China relationship is that Congress prohibits any collaboration between them. “Most national space programs have a military element, but that’s by far the largest in the US, and generally small in Russia and China.”

Harvey estimates that military elements make up about 15-20% of China’s space program, which isn't massive, totaling some $4.9bn compared to the U$35.9bn of the US, $5.7bn of the European Space Agency (ESA), Russia’s $3.2bn, Japan’s $3bn and India’s $1bn, according to Euroconsult.

Will CNSA ever challenge NASA or Russia’s space agency ROSCOSMOS for dominance in space tech? Harvey calls China’s space program ‘extremely economical’ and stresses that it concentrates only on certain areas. “It all precedes at a fairly slow pace, but don’t be deceived by that,” he warns.”Ultimately it’s going to catch up with a lot of any other countries.”

TechRadar's Next Up series is brought to you in association with Honor

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),