EU Copyright Directive: what does it mean, and should you be worried?

The end of the web as EU know it?

To say that copyright is a complex area is an understatement. Copyright law and the nuances therein can arguably make quantum physics seem relatively straightforward to understand. And when those laws change, with new regulations ushered in, matters can become more confusing than ever.

And such is the case in the European Union right now, following the passing of the EU Copyright Directive by the European Parliament earlier this week. But what exactly is this legislation – also known more clumsily as the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market – when does it come into force, and what does it all mean in reality?

Is this the end of the road for posting fun memes or animated GIFs showing scenes from big-name movies, due to potential copyright issues from the relevant film studios?

Read on for the full lowdown on this legislation and its likely effects on you.

- Have Europeans lost control over their personal data?

- Opinion: the EU's Copyright Directive isn't just bad for memes, it makes Big Tech harder to beat

What is the EU Copyright Directive?

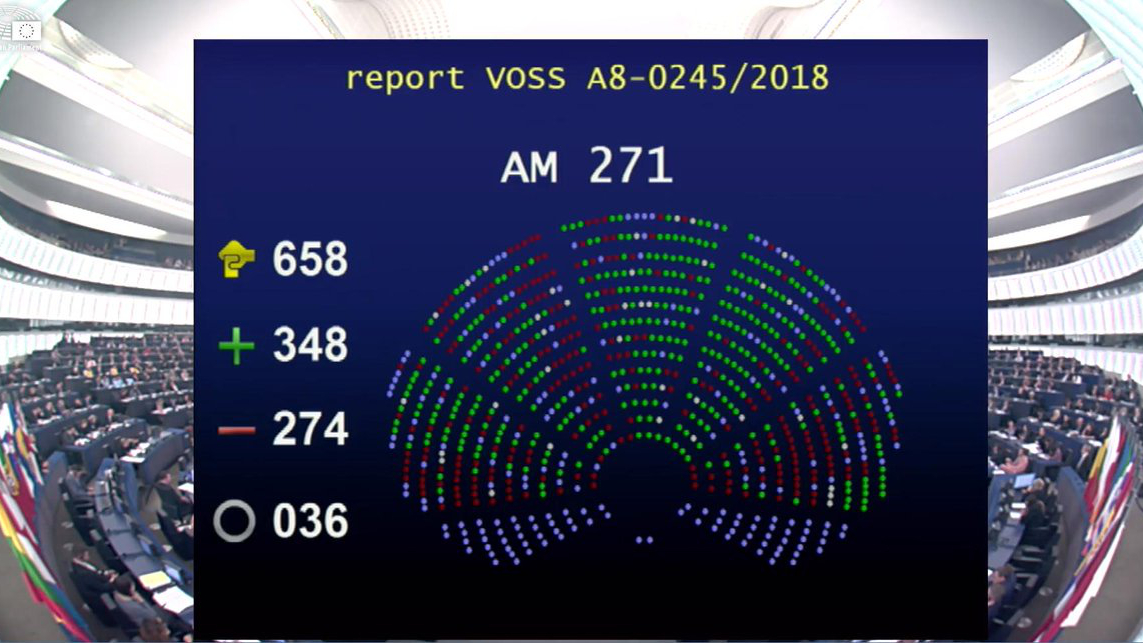

The Copyright Directive is a piece of EU legislation that was passed by the European Parliament on March 26, with 348 MEPs in favor versus 274 against. The Directive comprises of a raft of measures designed to reform the way copyright works in the EU in order to “protect creativity in the digital age” in the words of the European Commission. Others don’t see it that way, though, and we’ll look at the arguments for and against shortly.

There are numerous articles and points of reform therein, but it is Article 11 and 13 of the Directive which have sparked controversy. Article 11 has been informally dubbed as the ‘link tax’, which could be seen as slightly misleading as it is not imposing any kind of tax on hyperlinks as such. Instead, this is a measure primarily aimed at large online platforms – news aggregators like Google News, or big social media sites – who display snippets of the news stories they are linking to, and will be charged for using that small section of text.

The biggest furore, however, has surrounded Article 13, which puts fresh responsibilities on the shoulders of online content platforms to ensure that any media uploaded does not infringe copyright. Content platforms like YouTube must obtain licensing agreements with rights holders for uploaded media, or make their “best effort” to ensure that users don’t make unauthorized content available on the site. However, there are a lot of potential ramifications and nuances here, which we’ll discuss momentarily.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

As you would expect, the legislation only applies to countries in the European Union. However, it is bound to have a much wider impact on a global scale, particularly with regard to the US tech giants such as Google or Facebook which will obviously be affected by the legislation in their European operations.

What are the arguments for and against the EU Copyright Directive?

Broadly speaking, the aforementioned tech giants are against the EU Copyright Directive, for clear enough reasons in the case of Google, for example. However, a host of pro-internet freedom activists are also firmly against the incoming legislation. The European Commission is strongly in favor of the new regulations, of course, as are many publishers and rights holders from the likes of the music and film industry.

As mentioned, Article 13 is the big thorn in many people’s sides, so let’s unpack that one first. The central fear here is that this could force online content platforms to adopt ‘upload filters’ to strongly vet user-uploaded content for copyright infringing material, and that this in turn would produce a number of issues, and will generally speaking lead to less freedom and more censorship of the internet.

The European Commission (EC) has a FAQ which poses the question: “Will the Directive impose upload filters online?”

The EC’s answer is: “No. The text of the political agreement does not impose any upload filters nor does it require user-uploaded platforms to apply any specific technology to recognise illegal content.”

The EC further clarifies that “certain online platforms will be required to conclude licensing agreements with rightholders” when it comes to copyright-protected content, and if these licences aren’t agreed, the online platforms must make their “best efforts to ensure that content not authorised by the right holders is not available on their website.” And it reminds us again that this ‘best effort’ obligation “does not prescribe any specific means or technology.”

Opponents of Article 13 have a number of big problems with all this, including the prospect of content hosting sites having to pre-emptively determine material they may need to license – which when you think about it, could be a ridiculously wide-ranging swathe of content.

However, the main issue is that while online content platforms are not being forced to implement some kind of upload filter, they will likely impose them anyway, to defend against being caught out by potential user-related copyright violations (which they will be held responsible for). In other words, these companies will be thinking: better safe than sorry.

And any such filters will likely get things wrong sometimes and incorrectly sensor material which does not infringe copyright, particularly if the content platform is erring on the side of caution – better safe than sorry – when it comes to policing the material uploaded to the site.

While Article 13 is designed to funnel money away from content-sharing giants like YouTube, and redistribute it into the pockets of artists whose music or videos are being used on the sites, it could backfire in some respects and actually solidify the likes of YouTube’s online dominance.

That’s because only the big sites will be able to afford and properly hone systems to defeat copyright violations, so smaller companies – and potential future rivals – could be hung out to dry, if it isn’t realistically viable for them to operate without such policing measures.

And speaking of the cost of these systems, who will ultimately foot the substantial bill here? As ever, it’s most likely that the expense will be passed down the chain to the end-user, in one way or another…

Moving on to Article 11, the theory here is that the likes of Google and Facebook make a lot of money out of sharing other outlets’ news stories, so getting them to pay to license snippets of the stories – typically shown under the link to the article, to briefly illustrate the content therein – again takes money from these tech giants and redirects it to the original creators of the content. In short, the aim is an overall fairer distribution of revenue to include the little guy (or at least ‘littler’ guy) as it were.

The EC clarifies that when it comes to this ‘link tax’, the legislation explicitly excludes “individual words and very short extracts” of news articles, so the law will remain unchanged in these cases.

However, is this inviting a future worldwide web full of bare links or pathetically uninformative truncated snippets of article descriptions? A much less useful web for the average surfer, in other words? It really all depends on the definition of a “very short extract”, naturally enough, which is unclear at the moment. So we really need for that to be clarified in much more concrete terms.

Further flak has been fired at Article 11 in terms of the idea of a ‘link tax’ having been tried before in Europe – for example, in Germany, where it completely failed to have the desired impact.

What does the EU Copyright Directive mean to you in practical terms?

Right now, nothing has changed regarding how copyright is enforced online – not yet, anyway. The Directive still needs to get its final approval from the European Council next month. And after that, it’ll likely still take a good deal of time for individual EU countries to enact the Directive. As the EC notes: “Member States will have 24 months to transpose the new rules into their national legislation.”

So nothing changes immediately, and there is also the question of exactly how the regulations will be interpreted by each individual country. Furthermore, in the case of the UK, it may not be in the EU by the time we get that far down the line. That doesn’t mean the UK won’t be affected by the Directive, though, just like the US and other nations, in terms of the broad changes to the net in Europe.

When the new laws do come into play, at the level of an individual, will Article 11 mean that you could somehow be hit by the ‘link tax’ for linking to a published news story like Google News does? No, in short, as the EC clarifies that the new rules “will only apply to online uses by commercial services, such as news aggregators, and uses of press publications by individual users are explicitly excluded.”

However, as we mentioned above, this particular article does potentially threaten to usher in a less useful web for the average punter in terms of severely cropped link descriptions.

Another big question floating around in recent times pertains to Article 13, and whether folks will be unable to post a simple meme thanks to potential copyright implications. This isn’t the case, either, as the EC notes that: “Uploading memes and other content generated by users for purposes of quotation, criticism, review, caricature, parody and pastiche (like GIFs or similar) will be specifically allowed.”

So you don’t have to worry about this, at least not in theory, but the further concern here is that if online media platforms feel compelled to implement some kind of content filter, as previously discussed, the likes of memes may end up being errantly blocked by these copyright policing algorithms. After all, ensuring the accuracy of these sort of mechanisms is a hugely tricky business.

Ultimately, it’s clear that a lot still rests on the exact interpretation and implementation of the legislation, and how the battle between the tech giants like Google versus the law-makers and media copyright holders plays out.

The details matter, and we look forward to working with policy makers, publishers, creators and rights holders as EU member states move to implement these new rules. #Article11 #Article13 (2/2)March 26, 2019

For now, Google is being relatively diplomatic, as you can see from the above tweet, but if the German ‘link tax’ episode is anything to go by, the internet giant will (unsurprisingly) not be afraid to throw its considerable weight around.

- What is GDPR? Everything you need to know about the new EU data laws

Darren is a freelancer writing news and features for TechRadar (and occasionally T3) across a broad range of computing topics including CPUs, GPUs, various other hardware, VPNs, antivirus and more. He has written about tech for the best part of three decades, and writes books in his spare time (his debut novel - 'I Know What You Did Last Supper' - was published by Hachette UK in 2013).