Facial recognition technology is being used to diagnose rare diseases

It's good for more than just image tagging

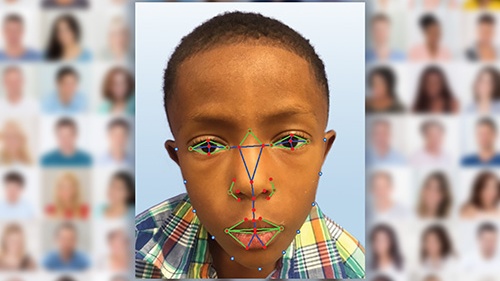

Facial recognition software has been used by medical researchers to diagnose a rare genetic disease that has previously been particularly difficult to spot in people of African, Latin American and Asian descent.

The disease, 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, also known as DiGeorge syndrome and velocardiofacial syndrome, is difficult for healthcare providers to diagnose in diverse populations largely because it manifests itself as multiple defects throughout the body, including cleft palate, heart defects, a characteristic facial appearance and learning problems.

According to Paul Kruszka, M.D M.P.H, a medical geneticist in NHGRI’s Medical Genetics Branch “Human malformation syndromes appear different in different parts of the world,” and that as a result “even experienced clinicians have difficulty diagnosing genetic syndromes in non-European populations."

Early action

The researchers from the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), part of the National Institutes of Health found that when studying the clinical information of 106 participants and photos of 101 participants with the disease from 11 countries across Africa, Asia and Latin America, appearances across the groups varied widely.

By testing the facial recognition technology themselves to compare a group of 156 Caucasians, Africans, Asians and Latin Americans with DiGeorge syndrome to those without the disease, the researchers were able to make correct diagnoses for all of the ethnic groups 96.6 percent of the time.

The hope is that creating a database and using facial recognition technology will help these healthcare providers better recognize and diagnose DiGeorge syndrome and deliver the necessary interventions as early as possible.

If the technology goes as far as hoped, it could one day be possible for healthcare providers to simply take a photo of a patient on their smartphone, have it analyzed and very quickly receive a diagnosis.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Further potential

It’s not just DiGeorge syndrome that the technology could be used to diagnose either – in a study published in 2016, researchers found that the technology was also very accurate when diagnosing Down syndrome. The next move is to see how successful it would be with cases of Noonan syndrome and Williams syndrome, both of which are rare but are seen by many clinicians who would find the technology useful.

As a result of the research, DiGeorge syndrome and Down syndrome are now part of the Atlas of Human Malformations in Diverse Populations.

When the atlas is completed it will contain photos of physical traits of people with many different inherited diseases around the world, including Asia, the Indian subcontinent, the Middle East, South America and sub-Saharan Africa as well as written, searchable, descriptions of those affected.

This is a significant step forward as previously the only available diagnostic atlas available to healthcare providers featured photos of patients with northern European ancestry. Naturally this isn’t ideal as it doesn’t represent how these diseases manifest themselves in patients from other parts of the world, making it extremely difficult for doctors who have never encountered them before to make an informed diagnosis.

Maximilian Muenke, M.D., atlas co-creator and chief of NHGRI's Medical Genetics Branch said that now healthcare providers in the US and other countries with fewer researchers will have access to the atlas as well as the facial recognition software. Ideally this will result in more early diagnoses and early treatment “along with the potential for reducing pain and suffering experienced by these children and their families.“

Emma Boyle is TechRadar’s ex-Gaming Editor, and is now a content developer and freelance journalist. She has written for magazines and websites including T3, Stuff and The Independent. Emma currently works as a Content Developer in Edinburgh.