For its next trick, blockchain plans on making recorded music profitable again

Harmonic notes

In recent years most discussions of blockchain technology have related to Bitcoin, the digital currency that recently saw its value skyrocket to over $19,000 before plummeting to just over $7,000 at the time of writing.

But while cryptocurrencies are the most widespread use of blockchain, in truth its potential use cases are many and varied, and the latest problem that blockchain enthusiasts want to solve is ensuring that musicians are fairly compensated for their songs.

Enter Choon, a new streaming service co-founded by the DJ Gareth Emery. Choon plans to harness the transparency and record-keeping advantages of blockchain to cut out the middle men and deliver revenue directly to artists.

As Emery describes it: “Our way of doing royalties and accounting was basically designed in the days of jukeboxes and sheet music and has been grandfathered in across every new innovation, and we just have a system that is completely not fit for purpose.

“Rather than trying to innovate on top of a system that is fundamentally flawed we're trying to create a new system that has no connection to the old one.”

It’s a bold ambition – but does Choon have any chance of succeeding in a world dominated by the likes of Spotify and Apple?

The problem

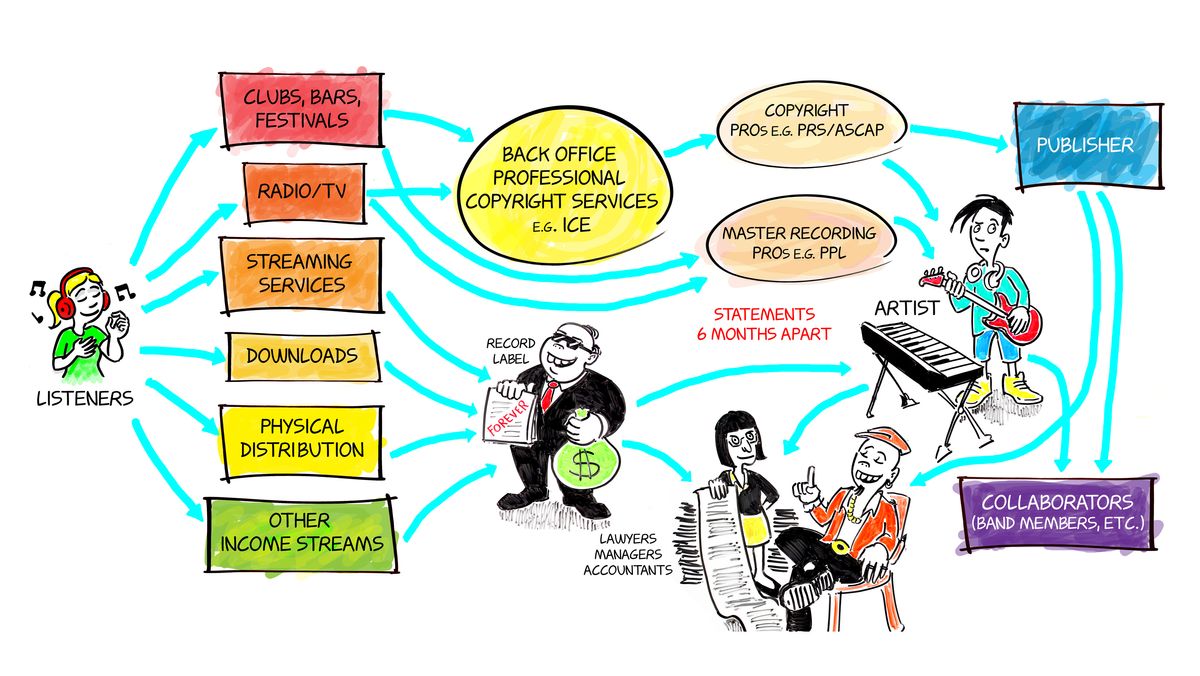

In Emery's view, the current problem with the music industry is that there are too many middlemen, with each of them demanding their cut of the profits, leaving close to nothing for the artist who actually created a track.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

These middlemen range from record labels, publishers and copyright societies to the streaming services that package up an artist’s music and delivers it to fans.

“We've all been sort of sold this myth that there's no money in recorded music,” Emery explains. ”There is actually – it’s a $16 billion dollar industry– it just goes to the wrong people.”

And Emery’s argument isn't just that these middlemen suck up too much of the money in the recorded music industry, but that their very existence is undemocratic. Emery shares stories of managers encouraging artists to wish Spotify’s playlist curators a happy birthday on Twitter, or send them gifts to secure a spot in a playlist with millions of subscribers.

“Careers can get made or broken by being in those playlists,” he adds.

Emery talks about his own experiences of having to schmooze the curators of the electronic music playlist, and says it’s similar across other music genres. “I guarantee you now that if you had somebody here from an indie rock band they would know who the power player is who creates those playlists for indie rock, and they would know how you get on their side.”

The fact that the music industry also continues to be dominated by male acts lends yet more weight to the argument that the industry’s trendsetters are out of touch.

The solution?

Choon’s solution is twofold. First, it will dispense with all aspects of human curation of its homepage.

“There's gonna be no smoke and mirrors about how our home page is structured,“ Emery explains. “When we use algorithms to work out what you get shown, we will publish those in transparent ways so everyone knows exactly why a release is in its position.”

Not only will this hopefully eliminate what Emery implies is the nepotism that’s developed around Spotify’s human-curated playlists, it'll also allow Choon to – in theory at least – be run with a much smaller staff than other, bigger streaming services.

The second part of the equation is simplifying the complicated process of assigning and paying royalties based on how frequently artists are streamed – and that’s where blockchain comes in.

Emery is keen to emphasize that blockchain technology is not at the core of every part of the Choon ecosystem. Instead it’s a two-tiered system, consisting of a more traditional streaming service infrastructure and an Ethereum-based blockchain to log streams and ensure that artists get paid.

“When I get paid royalties right now I get 300 pages which come from my record label showing what they were paid from Spotify. It's probably two years since the streams took place, and it is completely impossible to know whether what I'm getting paid is actually correct,” Emery explains.

“When I get paid royalties right now I get 300 pages which come from my record label showing what they were paid from Spotify“

In contrast, Emery wants Choon’s system to be completely transparent. Anyone and everyone will be able to see exactly how much each artist is being streamed, no one will be given preferential treatment, and you’ll even be able to be paid daily rather than waiting for what Emery says can be years to get your royalties from streams.

Underlying the open nature of the blockchain-based system that Emery and his team have created is the fact that the DJ would be perfectly happy for other companies to build their own streaming services on top of the infrastructure– even Spotify could, if it was so inclined.

Thanks to this transparency and streamlining, Choon plans on passing 80% of its revenues back to the artists while only taking 20% for itself.

Bum Notes

But cashing out is where the system gets a little messy.

It shouldn’t come as that much of a surprise that a streaming service based around blockchain would choose to pay its artists in cryptocurrency, but what could raise some eyebrows is the fact that Choon plans on paying its artists in an entirely new cryptocurrency called ‘Notes’.

Like other Ethereum-based currencies, Notes piggybacks on the existing infrastructure of the network, but builds in its own functionality specific to the requirements of Choon. The streaming service plans to initially distribute the currency via an initial coin offering (ICO), a common method of funding new cryptocurrencies, but once the ICO is completed Notes will become freely tradable.

But a cryptocurrency being freely tradable carries its own risks, specifically the extreme volatility that has become a staple of cryptocurrency markets. In a month that’s seen the price of Bitcoin fluctuate by as much as $10,000, isn’t Emery worried that this reliance on a digital currency will create more headaches for artists than it solves?

“We've been pretty frank... cryptocurrencies are volatile,” he responds. ”I think everybody kind of needs to look at their personal risk profile, and look at how much risk they want.

“I think the artist that would be nervous about those sorts of concerns, probably you're not gonna want to get paid in crypto. They're gonna want to get paid in fiat from the 99% of options [streaming services] available.”

Volatility is one thing, but there’s also no guarantee that Notes will hold any value at all. Choon can make all the claims it wants about paying more than competing music streaming services, but ultimately if it’s paying its artists in a cryptocurrency that turns out to be worthless then what’s the benefit?

Techno-utopia?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this reliance on an unproven currency to distribute royalties means Choon will launch with a library that’s closer in style to SoundCloud than to Spotify, consisting of around 400 independent artists who own their own music libraries, rather than those who are already signed to an existing label.

And Emery seems happy with not catering to the existing giants of the industry. “I'm not interested in Elvis and the Beatles, and I'm not interested in even, say, Calvin Harris and Ed Sheeran,“ he says. “Who I want is the Calvin Harris and Ed Sheeran who's in his bedroom right now making music... we're building the system for the future rather than trying to bolt a solution onto the system of the past, which is fundamentally broken.”

“I'm not interested in Calvin Harris and Ed Sheeran. Who I want is the Calvin Harris and Ed Sheeran who's in his bedroom right now making music“

But for those bedroom-based musicians, contributing their music to Choon will initially be an act of faith rather than a means to get rich quick. This won’t be a situation where they’ll earn money regardless – they’ll need the system to succeed in order for Notes to have value that they can exchange for real currency.

Emery, unsurprisingly, is optimistic that the ‘mission’ (as he calls it) will pay off.

“When I first got into Bitcoin it wasn't so much that I thought 'at some point this Bitcoin that I'm paying $200 for is gonna be worth $10,000' – I just believed in the thing. I was a believer in the mission.”

And with revenues from recorded music having gotten so low, it might be that the slim chance of a new system might be better than the guarantee of the revenues of the existing one.

For Emery, ultimately it all comes down to making better music. “We're all touring all the ****ing time because it's the only way any of us make any money. Being on the road 250 days a year is actually not the best for making outstanding art… there is an intention here of just increasing the quality of the music we're making.”

Jon Porter is the ex-Home Technology Writer for TechRadar. He has also previously written for Practical Photoshop, Trusted Reviews, Inside Higher Ed, Al Bawaba, Gizmodo UK, Genetic Literacy Project, Via Satellite, Real Homes and Plant Services Magazine, and you can now find him writing for The Verge.

Most Popular