Games still haven’t got bisexuality right

Opinion: Developers need to consider what it means for characters to be queer

Welcome to TechRadar's LGBTQ+ Gaming Week 2021. During this week-long celebration, we're highlighting topics and voices within the LGBTQ+ gaming community. Find out more here.

A decade ago, I met my first playersexual character in Choice of the Vampire: Clotho. Clotho is an African voodoo priestess in 1800s New Orleans, who fell in love with the spunky vampire lady I was controlling. As a queer teen, I was delighted Clotho wanted to date a woman. But when I replayed the game as a male player character, I realized her dialogue was the same. Clotho doesn’t love your vampire, in all their debonair or bloodthirsty or compassionate choice-based glory; she loves the thing marked ‘Player Character’, regardless of gender. That’s what it means to be playersexual.

That choice was… fine. For one character. For one game. In the real world, bisexuality means being attracted to genders like your own and different to your own; it’s a sexuality that’s up to each individual to define for themselves. But when the gender-blind, sexuality-agnostic version of player-focused bisexuality becomes gaming’s default queer inclusion, it gets old fast. Games still largely imagine a world where heterosexuality is the norm, and bisexuality is an afterthought – a way for developers to make queer players feel included without having to do any of the legwork to make it feel authentic.

Instead of an identity, bisexuality in games is a mechanic. If you can date, why not let you date anyone? It stops players from getting mad that their favorite character is locked behind an incompatible orientation, and it’s easy to use the same dialog for everyone. But this view of bisexuality is hollow; it makes characters feel less alive if they like the player, no matter what. Playersexuality makes every relationship identical – and that makes all of them feel less special.

Harmful bisexual tropes

Bisexuality, both in real life and as portrayed in media, is often misunderstood and reduced to damaging stereotypes. The first bad trope is ’depraved bisexual’. Bisexuals are portrayed as undiscerning, omnivorous creatures full of lust. They might be greedy or promiscuous, dating multiple people at once or ‘putting out’ immediately. They might be involved in a threesome, or have way too much focus on their sex lives. Sometimes, that depravity becomes plain evil: it’s suggested that bi characters are really gay or straight, so being bisexual is itself a deception that marks a character as untrustworthy or traitorous.

" Crucially, in-game bisexuals never talk about being bi: they have no community, no reflection, no coming to terms with suddenly falling for someone else or discussion of when they first realized they weren’t straight. Maybe there’s no homophobia or biphobia to contend with, but there’s also no queer joy or exploration."

Some of these negative tropes turn up in Fire Emblem Fates (2015), a game that’s ostensibly about tactical warfare but which happens to have a deep relationship system. There are two playersexual characters in this: they can date a main character of either gender, but are otherwise exclusively straight. One of them, Rhajat, is a heavily sexualized dark mage who displays stalker-like behavior towards the main character regardless of gender, and remains obsessed with them even if she marries someone else. The other, Niles, is a sadistic rogue, whose omnidirectional flirting is a sign of his villainy: he’ll hit on anyone, while threatening to torture them for fun. Both fit the ‘depraved bisexual’ stereotype, with their attraction to multiple genders used to highlight their moral ambiguity.

The second bisexual flavor is ’not really bisexual’. These characters might mention that they’re bisexual, but are only even shown as being attracted to one gender. Or maybe they’ll just never address their sexuality, so it seems out of the blue when a burly divorced man suddenly admits he has feelings for a handsome hunk but doesn’t feel the need to comment on its novelty.

In video games, characters who have heterosexual options save for the player character can feel like this: they’re clearly supposed to be straight, but the power of being a protagonist makes that not matter. Crucially, in-game bisexuals never talk about being bi: they have no community, no reflection, no coming to terms with suddenly falling for someone else or discussion of when they first realized they weren’t straight. Maybe there’s no homophobia or biphobia to contend with, but there’s also no queer joy or exploration.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Fire Emblem: Three Houses (2019) is filled with characters who are straight. There are half a dozen playersexual characters, and another handful who can romance a specific partner (for example, a female main character can’t date Catherine or Shamir, two powerful women knights, but those knights can end up with each other). However, you wouldn’t know there were so many bisexuals running around, because all of them have far more straight relationship options than queer ones. And none of these queer characters ever talk to each other, even in passing, about their common ground of not being straight. Dorothea, who can end up with four women, has eight men she can marry. Though the game doesn’t try and push specific romances for anyone, it seems that even the queerest characters are designed to be erring heterosexuali: straight, with limited exceptions. This shallow view of queerness – treating it as essentially identical to heterosexuality – means that bisexuality feels like an afterthought.

Moving in the right direction

Playersexuality is not necessarily a bad choice – it’s just a bit lazy. But it’s definitely an improvement from the olden days of no representation at all. Take the classic farming game Harvest Moon: Friends of Mineral Town (2003), where you played as a male farmer and could romance five village bachelorettes. If you wanted to date a boy (or play as a woman), you had to buy a whole other cartridge.

Cut to a decade later, and there are two games both based on that title that have queer options: Stardew Valley (2016) and Story of Seasons: Friends of Mineral Town (2020). That progress is real, and worth celebrating. The farming sim genre often emphasizes completion; completing all of the romance events is just like growing all the crops. Dating everyone just means more content to explore.

"Playersexuality is not necessarily a bad choice – it’s just a bit lazy. But it’s definitely an improvement from the olden days of no representation at all."

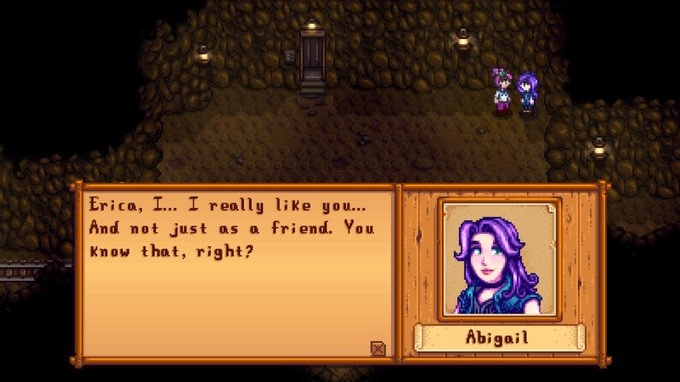

However, while Stardew Valley is a truly playersexual game, as it lets you date anyone – Leah the sculptor, Elliott the writer, Abigail the goth, Sebastian the loner – it uses the same dialog for straight or queer romances.

This means there’s no difference in how these characters approach you, or relate to you, or reveal their feelings for you. Elliott, for example, reads as a flamboyant dandy: what if he struggled to articulate his feelings for a woman, because he was used to being perceived exclusively as gay? Wouldn’t it be interesting if, in the same story events, Abigail bro’d down with a boy but got tongue-tied talking to a girl?

Despite the town’s universally bisexual 20-somethings, the inhabitants are all hinted to have straight crushes. Leah and Elliott are implied to have feelings for each other, as are Abigail and Sebastian. If the player hadn’t shown up in the village, there’d be no organic queerness there at all. (Leah is sort of an exception: her ex, Kel, who is always the same gender as the player character, briefly appears.)

Story of Seasons takes those crushes a step further. All the villagers are split into straight couples whose relationships actually progress if you’re not chasing those romances. There are ‘rival’ events, which play out vignettes from slow-burning romances between heterosexual pairs. This adds some internal life to the characters, making them more than just objects of affection waiting to be wooed.

Dragon Age 2 and Dragon Age Inquisition both did a similar thing in terms of letting romance options woo each other – but in DA, you couldn’t romance both parties and still have them develop feelings for each other. In Story of Seasons, nobody seems to notice if you’ve seduced all 12 eligible millennials.

Better bisexualities

Bisexual people come in all shapes and stripes. Some of us are more attracted to people of the same gender but don’t want to discount any possibilities. Some of us are truly in-the-middle disasters with equal-opportunity heartbreak policies. Some of us only have opposite-sex relationships because it’s easier to understand straight romantic cues in a world that invalidates queerness. And there’s more nuance in between all of these – bisexuality is so broad and varied that you can’t reduce it to a single experience. All of these are valid expressions of bisexuality, and it sucks that games almost invariably represent us with a straight-until-proven-otherwise playersexual.

"I want something that doesn’t play into damaging tropes; that recognizes bisexuality as varied rather than monolithic; and that lets characters connect with their fellow queer pixel-people."

So what does better bisexual representation look like? I want something that doesn’t play into damaging tropes; that recognizes bisexuality as varied rather than monolithic; and that lets characters connect with their fellow queer pixel-people. Bisexuals don’t have to spend all their in-game dialog lusting after people of multiple genders to be authentically bisexual; they just need interest beyond the player.

That isn’t to say all games get bisexuality wrong. Indie games often take the lead when it comes to LGBTQ+ content, and bisexual representation is no exception. Dating sim Dream Daddy (2017) has you play as a dad dating other dads, but some of them (including potentially the player character) have dated women in the past, and it’s not a big deal.

That’s significant, because bi men are rarely acknowledged at all in the media or real life – they’re often victims of bisexual erasure, the assumption that they’re either really straight or gay, and are constantly asked to prove their identity is valid; having bisexuality be accepted in such a low-key way makes for positive representation. Night In The Woods (2017) also has some very casual representation: the main character, Mae, when asked about her dream date, says “I don’t care if it’s a guy or a girl”. She has also been confirmed to be pansexual by artist Scott Benson. Mae never says ‘pansexual’ or ‘queer’ in the game – but as a 20-year-old still figuring things out, that feels true to her character.

Conversely, the Monster Prom series (2018-) makes its world one of high-octane bi representation. The characters are magnified caricatures of high-school tropes who feel larger than life, expressing attraction to each other without the player having to prompt them, and are omni-horny as part of their ebulliently chaotic personalities. While this kind of everything-that-moves bisexuality representation can be damaging, Monster Prom is clearly aware of this trope, and celebrates the joy and camaraderie that rampant ambi-directional lust can bring. It’s deliberately silly and tongue-in-cheek, which feels very queer.

Obviously, bisexuality isn’t the only kind of queerness we want from games. But when playersexual, straight-coded characters are given to us as the primary form of queer representation, it’s not unreasonable to ask for more. Give us more queer creators writing more queer characters. Give us more bisexuals who are in loving, committed relationships, and who don’t just want to date the player character. Give us someone who just wears a bi pride flag as a shirt and actively identifies as ‘bisexual’ rather than ‘not interested in labels’. Just give us something more.

V. S. Wells is a British writer and journalist living in Vancouver, Canada. Their work has appeared in places including Slate, Metro, Toronto Star, VICE and Xtra. When not writing, you'll find them playing board games, making a mess in the kitchen, and trying desperately to keep their houseplants alive. Follow them on Twitter at @vsmwells.

V. S. Wells is a British writer and journalist living in Vancouver, Canada. Their work has appeared in places including Slate, Metro, Toronto Star, VICE and Xtra. When not writing, you'll find them playing board games, making a mess in the kitchen, and trying desperately to keep their houseplants alive. Follow them on Twitter at @vsmwells.