For performance and sales reasons, most games were stuck in what was dubbed 2.5D until the launch of Quake in 1996. Quake wasn't the first genuinely full-3D shooter in the modern style, but it was the one that made 2.5D officially obsolete.

These faux 3D or 2.5D games were flat maps, where areas could be raised and lowered (and in later games like Duke Nukem 3D, sloped), but you couldn't have one room on top of another.

Some games pretended otherwise, but it was generally a trick – the player would be silently teleported as they crossed the room's threshold. Descent provided a full 3D world made up of polygons in 1995, but only a basic one – it was a series of sprawling mineshafts. The Star Wars game Dark Forces offered rooms above rooms, but otherwise stuck to the standard technologies on display in any other shooter of its era, including sprites.

Sprites were a growing problem. By the mid '90s, level design was getting more and more impressive. By modern standards, the opening cinema level in Duke Nukem Forever is empty and unconvincing, but to an audience used to bland military base corridors and castles, the realism was incredible.

Almost all these games were able to do this because they saved their 3D for the world. Actual characters were pre-drawn 2D images, pasted in to the game. Not only did they increasingly look weak, not part of the scenery and incredibly blocky up-close, but they also didn't fit.

Games could scale sprites to deal with the player getting closer to and further away from them, but when they started offering the ability to look up and down (first made popular with Heretic, a 1994 fantasy game) the effect showed its limits, with sprites shearing and increasingly looking like the cardboard cutouts they were.

A little voodoo magic

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Games had to get more advanced, but the performance wasn't there. Quake brought full-3D worlds and enemies to the field in 1996, but at the cost of visuals.

3D GAME CHANGER: First-person shooter bosses like this were unheard of before Quake was released in 1996

Technically, they were better, and the improvement in animation was stunning – an early sequence where a snarling Fiend leaps out of a door to attack the player directly is one of many gamers' fondest memories, to say nothing of the first episode's room-sized, lava-throwing monster Cthon. But the world was still drab, ugly and simplistic, with enemies that looked like they'd been knocked into shape with a sledgehammer and textures that would have lowered the tone in a morgue.

Like all graphics technology, this quickly improved over the next few years, but it was increasingly obvious that simply throwing more CPU power at games wasn't going to cut it. Not alone, anyway.

Most people didn't really see the need for dedicated video cards at first because, to put it bluntly, there wasn't much of one. Games increasingly offered a high-end mode that offered a higher resolution and additional effects without a specific need for extra hardware – bar a hefty processor.

This high-end mode slowly became the standard experience, yet it was a long time before video cards became mandatory for playing PC games. Even technical showpieces like the original Unreal would run in so-called 'software mode'. There wasn't one big game that marked the transition, more a slow giving into inevitability.

Dedicated 3D cards came into their own around 1997, with several competing, mutually incompatible brands fighting it out for dominance. By far the most successful was 3DFX with its Voodoo cards. Even now, with built-in low-end 3D a standard on motherboards, a separate 3D card is mandatory for most games. On the plus side, the dominance of DirectX means that you don't need to worry too much about which card to buy.

Individually, the abilities offered by 3D cards don't sound too exciting. In the late '90s, the core functions were transformation, clipping and lighting – in short, getting the card to work out where items in the world were and how they should be lit.

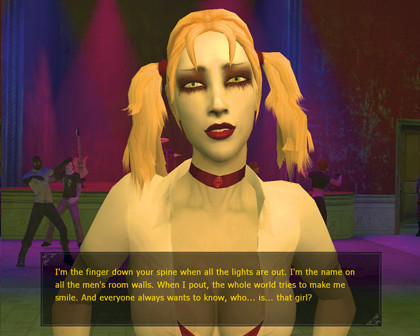

BODY LANGUAGE: Realistic character and facial animation is a surprisingly recent addition to gaming

The next big advance was the addition of shaders. Shaders are additional calculations thrown into the rendering pipeline that work on individual pixels, vertices and pieces of geometry to add effects and change the final image.

Examples include working out appropriate shadows, making a flag flutter or adding bump mapping (a texture that gives the illusion of raised and lowered areas on an object without the need to add polygons). More advanced shaders include motion blur and bloom effects, soft shadows, depth of field and volumetric lighting.

The new bottlenecks

With the technology burden eased (or at least partly passed onto the card manufacturers), developers could focus on making the most of what they had. Valve largely pioneered skeletal-based characters rather than keyframe-by-keyframe animated enemies in Half-Life, and Ritual went out of its way to create interactive elements such as hackable computers in the realworld environments of Half-Life's closest rival of the time, Sin.

Ragdolls spread to every new game until the games that didn't offer them felt stodgy and ancient in comparison. Most importantly, the new realism of these games finally let developers sink their teeth into genres that they'd never have been able to do as traditional corridor shooters. Grand Theft Auto III gave us a living city. A million games brought the horrors of World War II to life in glorious cinematic style. Problem solved? No, just replaced.

Now the issue became one of creating all this in the first place. A simple maze-based 3D shooter could be churned out in under a year by a competent team, but building cities, battlefields and other real-world elements requires an immense number of assets.

Games are much shorter than they used to be, not because they're more complicated – in most cases, the features are more advanced but the thinking is more conservative – because of the amount of content required, and the cost of making it.

There are shortcuts for some things, like the Speedtree libraries for procedurally generating a forest in a hurry (used in, among many others, Grand Theft Auto IV, Elder Scrolls: Oblivion and Fallout 3), but in general, if a developer wants something, that developer has to make it himself.

Technology itself has also reached a plateau, not because there's nothing more to do – nobody thinks that – but because right now, the big money is on Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3. Both are relatively old machines, but that doesn't matter. PC ports often allow for higher resolutions and sometimes let you switch on better graphics (Metro 2033 looks much better for instance, as will Crysis 2 when it lands) but it's usually a token gesture.

THE FUTURE: Crysis 2 is the current state of the art: explore New York in the wake of an alien invasion

To put the graphical difference into context, many PlayStation 3 games don't even use anti-aliasing to smooth out the edges of their polygons, and games on both platforms typically render at a lower resolution than the high-def numbers you'd expect from the systems' marketing.

The big change on the way is that 3D is about to become... 3D. Unlike films, games can create a stereoscopic image on the fly, with PlayStation 3 currently being updated to take advantage of this. You'll still need the silly glasses and a new 3D TV, and it's likely to be a headache-inducing gimmick for the most part, but a bit of depth in the right place could make it an interesting concept.