The science and art of level design

We examine the evolution and influence of level editors

Anyone who has been a gamer over the past decade or so will have noticed that many games shout about an additional creative feature: the level editor.

These allow us, the players, to produce maps for our favourite games, and to feel like we're giving something back to the gaming community when we share them online.

These tools are, of course, rooted in the actual tools that game development studios use to make the games in the first place, and it's the significance of that toolset, for both commercial and hobbyist purposes, that we'll be examining.

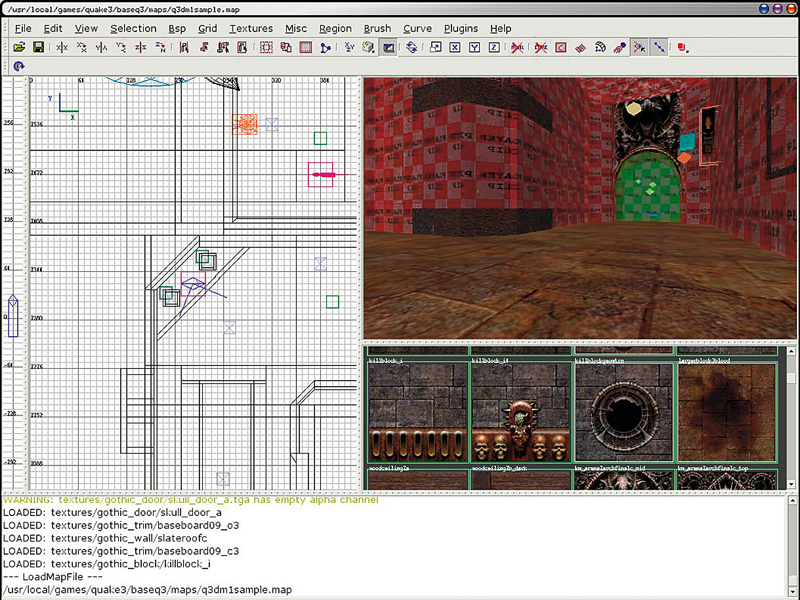

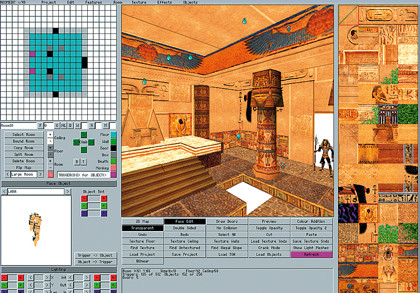

Way back at the time of Doom lots of us picked up the editor and began to work out how to turn these line-models into playable levels. It was fiddly stuff, and not exactly the most obvious process. Reading tutorials was a must.

Nowadays, however, things are a little shinier, and seemingly a little more straightforward. As the tech has developed, so the design process has moved onward, giving us new stuff to play with at home. Powerful editing suites for games such as Unreal Tournament 3 and Crysis give us far more instant gratification and flexibility than ever before, and yet the flipside of that is complexity.

Loading up one of these editors and playing with its toolset gives the impression that these game-authoring tools are more accessible and easier to use than previous generations, and yet commercial operations talk about games being harder to make than ever before. Mods for big games are taking longer, and maps are become a colossal undertaking.

So what's really going on with level design? Is it really becoming too complex for the hobbyist? That's been id's excuse for not supporting mods in Rage, for instance.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Have we already lost the art of the one-man level? We'll talk to some of the experts who use the current editors, see how the process has changed in the past decade, and examine some of the strange applications that people ending up finding for game level design. Could level design possibly be… art?

Level design is one of the fundamental processes of game development. Building the 3D environments we play our games in is a talent that underlies a huge number of gaming experiences, from Tomb Raider to Wipeout.

It's probably within the first-person shooter genre that this process is at its most visible, since the level-editing kit is regularly released to us, the gaming public. Many level designers start out using these tools and then find their way into the industry proper.

One such case in point is Neil Alphonso, a level designer currently employed at UK studio Splash Damage, where he's making the new shooter, Brink.

"I worked in special effects and editing for television and film after graduating," says Alphonso, "but after some introspection I thought I had the necessary skills to take a different career path, one in games. I took the time to learn an engine and started making maps, and in a total case of being at the right place at the right time, I landed a role on the first Tom Clancy's Splinter Cell game."

Alphonso's career path following this decision was pretty exciting, even by jet-setting games industry standards: "I then worked on a game called Shadow Ops: Red Mercury, and then spent some time on the infamous Duke Nukem Forever, before moving to Holland to work on Killzone 2."

Alphonso is now working on a multiplayer shooter, a genre that can be regarded as the heartland of level design, because it's where so many designers get started. This is evident in the kinds of maps that Alphonso mentions as classics, when we prod him for some suggestions:

"The first levels that always come into my mind are 'The Dark Zone' and 'The Bad Place' from the original Quake (DM4 and DM6, respectively), as they played a huge role in my decision to pursue a career in the games industry. A more recent single player focused example is the outstanding 'All Ghillied Up' for Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare, a level in which you re-enact a past mission of your hard-nosed CO. All three of those levels would certainly qualify as classics among level designers, but by now that list has gotten pretty large!"

A craft refined

What we've seen in the past ten years is very much a refinement of the level designer's art. Great levels, in which everything is built to lead the experience, without ever betraying that to the player.

While a multiplayer deathmatch level might need to be essentially donut-shaped and circular (so that players can move through the level to pick up weapons and not become trapped by their opponents), other game designs demand other kinds of environments: open levels that close down into corridors so you can perform specific objectives, for example, or the non-linear levels that allow you to explore but create paths so that you don't get lost, such as in STALKER.

Ever notice how you get lost far less in modern games than in the games we saw a decade ago? Probably not, because it's such a subtle effect.

Level design in single-player games has become the art of sign-posting, which is about pointing people in the right directions with subtle visual aids: a light here, a blood trail there. As Alphonso mentions, this is all encoded within the architectures that designers create.

"Levels like the original Halo's 'Silent Cartographer' have formed a sort of language that we can use to convey form, pacing, direction, and the other various aspects of level design," says the Brink level lead.

Level design is essentially a new frontier – a place where designers are learning to create artificial environments with constantly refreshed technology. What you learned two years ago might not be relevant in a couple of years time. It's a huge challenge to stay on top.

However, what has driven the development of level-editing tools, says Alphonso, is less about this craft, and more about the commercial concerns of the people who make game engines.