Don’t Look Up, which lands on Netflix this Christmas Eve, is supposed to be a comedy.

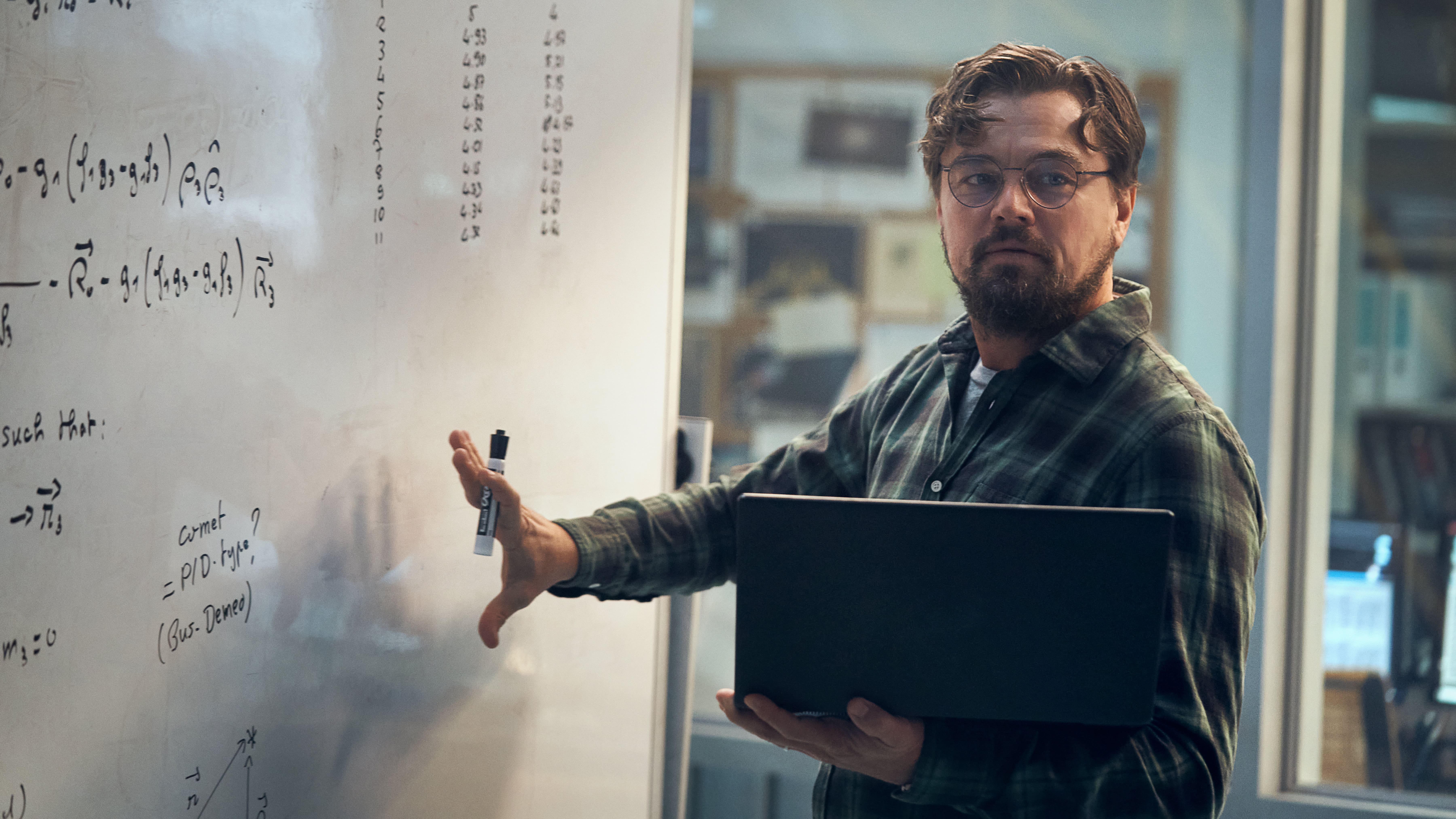

From the mind of The Big Short director Adam McKay, it tells the story of two astronomers, Dr Randall Mindy (Leonardo DiCaprio) and Kate Dibiasky (Jennifer Lawrence), who discover a planet-killing comet headed towards Earth. The pair set out to convince the world of the existential threat it faces, but have a predictably hard time selling the science to a society more interested in memes than meteorites.

A star-studded cast – so busy that the likes of Meryl Streep and Cate Blanchett are condemned to second billing on the movie’s poster – keep the jokes rolling for more than two hours, though viewers may find it hard to ignore the unsettling reality that simmers beneath the surface.

Don’t Look Up is a comedy, but it’s also a damning indictment of the political, economic and sociocultural climate in which the world finds itself in 2021. Put it this way: by the time the credits roll, you may find yourself wanting to detox from anything with a news feed.

Of course, existing McKay fans will know that uncomfortable satire is the director’s forte – The Big Short, Vice, and Succession (on which he’s an executive producer) all take a microscope to the messy politics of American capitalism – but in Don’t Look Up, he’s dealing in a different currency entirely.

To navigate the unfamiliar worlds of space and science, McKay enlisted the help of Dr Amy Mainzer, a professor of planetary science at the University of Arizona and lead scientist on NASA’s asteroid-hunting NEOWISE mission.

Ahead of Don’t Look Up’s digital release on December 24, we sat down with Mainzer to talk comets, comedy and her role in creating the movie’s bitter aftertaste.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Too little too late

“I think a lot of [Don’t Look Up] speaks to the reaction most people have when scientists have bad news to deliver,” Mainzer tells us over Zoom. “The movie is a parody, obviously, but it's taking a really satirical look at our unwillingness to listen to that bad news, even when we really need to.”

Meryl Streep plays President Orlean in McKay’s latest feature, a thinly-veiled caricature of today’s politicians, who often favor fans over facts. Upon hearing the warnings of DiCaprio’s Dr Mindy, she simply advises that the government “sit tight and assess” – which forces Lawrence’s Dibiasky into more drastic action.

The movie is a parody, obviously, but it's taking a really satirical look at our unwillingness to listen to bad news.

Dr. Amy Mainzer

“That [reaction] happens on all kinds of different topics,” Mainzer says, “not just asteroids and comets, but the pandemic, climate, severe weather, and so on.

“Science is telling us that if we take the following steps, we can significantly blunt the effect of whatever's happening. If we get on it and are proactive about responding to [bad news] using science-based approaches, we actually can avoid some of the worst outcomes.”

Mainzer won’t admit to being the real-life inspiration for Lawrence’s passionate astronomer, but there’s more than a hint of the former in the latter. “You know, I think Kate and I have a lot in common,” she tells us. “She is meant to represent one of the two strategies of scientific activism in the movie – [that desire to] get out and protest when you're not seeing governments or politicians taking action based on findings.

“The other style is represented by Dr Mindy, which is more like, ‘okay, you can protest, but these are the people over here who actually have the levers of power in their hands, so we have to try to work with them’. It's a struggle [between the two]. There's not always a clear cut answer, but we wanted to show the debate and the difficulties scientists face when trying to get the word out, to get people to take action.”

“And obviously, I'm a huge fan of Jennifer Lawrence,” she adds with a smile.

Scripted science

It would be remiss of us to not ask the celebrated astronomer on the other end of the line whether a planet-destroying comet could actually call time on humanity in the near future.

“The great news is that it’s a very, very, very unlikely scenario,” Mainzer says. “And we know this to be true because the last impact of this class was 65 million years ago – the one that wiped out the dinosaurs. It can't happen very often or we wouldn't be here, right? It's very unlikely that human life would have evolved if the planet was constantly getting pummelled by these big impactors.”

Well, that’s good to hear – although Mainzer is quick to add a caveat.

“The less good news is that there are plenty of objects out there that are large enough to cause what I would call severe regional damage, and we still haven't found most of those,” she says. “We have a lot more work to do there. So from my standpoint, the sensible thing to do is to just go look for these asteroids and comets.”

As well as advising McKay on “the role of science and society” for Don't Look Up, Mainzer was also tasked with designing the comet itself, and ensuring that the method of its discovery was portrayed as accurately as possible.

“I wanted [the comet] to be pretty realistic,” she explains. “I mean, the comet shown in the movie is fairly similar to the ones we've discovered in real life, and it's loosely modeled after comet NEOWISE, which we discovered last year.”

To the horror of Dr Mindy and Dibiasky, the object heading towards Earth in Don't Look Up is between five and 10 kilometers wide, and on course to strike the planet in around six months’ time.

There are plenty of objects out there that are large enough to cause what I would call severe regional damage, and we still haven't found most of those.

Dr. Amy Mainzer

“Obviously [in terms of its discovery], we compress the timeline. But it's perfectly plausible [to see a comet that late] – we discover comets all the time with only months before they make their close approach to the sun. But in terms of our ability to build spacecraft, usually it takes us longer than six months to put something together,” Mainzer says.

“So, what we would do depends a lot on the circumstances of the discovery. If we can find the objects when they're two decades away from any impact, we have lots of options, and our chances of being able to successfully move something out of the way are greatly increased. But you would have to use some pretty heavy duty explosives – and you would need time.”

Evidently, time isn’t abundant in McKay’s story – but that doesn’t stop opportunists attempting to take advantage of the situation. Mark Rylance plays eccentric tech investor Peter Isherwell in Don't Look Up, an eye-wateringly wealthy ‘visionary’ whose social media platform, BASH, has put the eyes of the world in his pocket.

After learning that the comet contains trillions of dollars-worth of precious minerals, Isherwell prioritizes its monetization over its destruction – though Mainzer explains that this plotline is a little too far removed from reality right now.

“It is true that asteroids and comets do tend to have a somewhat higher fraction of rare-earth elements in them,” she says, “and that's because of the way planets, asteroids and comets are formed. So yes, there’s been interest in trying to mine these objects for a long time.

“Unfortunately, that’s still pretty far in the future. It's not an easy thing to do. We actually have two missions that are in the process of bringing back samples, but these are like coffee can-sized samples, right? And each of these spacecraft cost a billion dollars. So it's just very hard to do.”

Sorry for the bad news, Elon.

Forward planning

Don’t Look Up is a rare breed of McKay film, then, in that it places the limelight on events that could happen, and are happening, rather than those that already have. The butt of the joke here isn’t a politician or business executive of yesteryear – it’s us, and how our behaviour right now is affecting our future.

Its climate change allegory is as unsubtle as it is pressing, and it's no wonder the movie's comedy so often borders on the uncomfortable. But Mainzer is more hopeful about the message behind Don’t Look Up.

“From my perspective, the film is saying: the future is up to us. We do have the power to choose the better outcome. We can make science-based decisions that will help us avoid the worst outcomes and select the best ones. So to me, the movie is actually very hopeful – we have the power to change things.

“You know, the very best art gets people thinking and creates conversations,” she adds, “and that's what we hope the movie will do. It should make you laugh, but it’s also a really powerful tool for helping us to reflect on ourselves a little bit and our behaviour. It's important to be able to laugh at ourselves, because that's the basis for humility and recognizing that we need to do better.”

For scientists like Mainzer – and the film’s fictional counterparts – the real threat comes from inside the Earth’s atmosphere. Discovering these existential risks is the easy part of their job; it’s up to society to then embrace their findings with an open mind and willingness to change.

It's important to be able to laugh at ourselves, because that's the basis for humility and recognizing that we need to do better.

Dr. Amy Mainzer

“Something that I think is important is for people to know scientists as human beings,” Mainzer concludes. “In other words, talk to your friends, talk to your neighbors, talk to your family, because getting to know the people who are the bearers of this information is the basis for trust.”

The final moments of Don’t Look Up are all about talking. Dare we say it, the earnest break in McKay’s relentless commitment to comedy might even make you a little emotional.

However you respond to the director’s disaster satire, though, take comfort in the knowledge that, as Mainzer says, we still have the power to change our ways. There isn’t really a comet heading towards Earth (yet), and we should be grateful that the end of days remains, for now, the plot of a Netflix comedy.

But it's on us to keep it that way.

Don’t Look Up will be available to stream on Netflix from December 24.

- These are the best Netflix shows to stream right now

Axel is TechRadar's UK-based Phones Editor, reporting on everything from the latest Apple developments to newest AI breakthroughs as part of the site's Mobile Computing vertical. Having previously written for publications including Esquire and FourFourTwo, Axel is well-versed in the applications of technology beyond the desktop, and his coverage extends from general reporting and analysis to in-depth interviews and opinion. Axel studied for a degree in English Literature at the University of Warwick before joining TechRadar in 2020, where he then earned an NCTJ qualification as part of the company’s inaugural digital training scheme.