Money and motivation

According to BitDefender's Catalin Cosoi, it's not just money that motivates botmasters. "Although it is easy to view botmasters as purely motivated by criminal gain, the factors of competition, kudos and building reputation play a key role in motivating many.

"We can broadly split motivations into two classes: the cyber criminal motivated by money and looking to maximise financial gain from their activities; and secondly, communities where several botmasters co-exist, leading to a strong competitive element. For a botmaster, having hundreds to thousands of machines at their command provides a good sentiment of power and arrogance."

Of course botnets are also about profit, as Trend Micro's Ferguson explains. "Money is made by criminals selling access to infected machines. Money is made by criminals distributing other criminals' software, and by using their botnets for that distribution. Money is made by renting out access to botnets for sending out spam, or carrying out distributed denial of service attacks."

Not surprisingly, malware that exploits existing infections is also appearing. Earlier this year, researchers saw the first instances of a new botnet toolkit called SpyEye, containing functionality to spy on the data being captured by computers infected with the Zeus software. It can even kill and replace the existing infection with its own zombie code.

"There's also a battle between the more advanced people who write their own code, as opposed to nicking code that's freely available, or stealing other people's botnets," says Dale Pearson of Security Active.

"Someone will try to uncover the botnets that other people have, then take control over them to build up their own net, as opposed to doing the hard work of phishing and spamming and getting people infected."

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Finding the botmasters

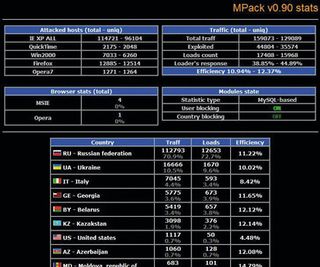

So where in the world are the botmasters? "It's a good question; it's an interesting question," says Ferguson "The straight, flat-out truth is that in terms of people who are running botnets, the phenomenon is truly global. I mean, if you take the example of Zeus, which is probably the most widespread crimeware kit, there's a great website called Zeus Tracker, and they will show you a live map of where the command and control servers for the botnets are. Obviously there are geographical concentrations, but they exist pretty much globally."

"Anyone from any country can be a botmaster," says PandaLabs' Corrons. "Your neighbour could be one, even if he's not an expert computer user, as we see from those involved and arrested in connection with the Mariposa botnet."

"Botnet herding seems to be an international pastime, like football," agrees Aryeh Goretsky of ESET, where he has the title of Distinguished Researcher. "We have seen botmasters from all around the world with varying skills and knowledge, ranging from minors in America who did not understand what their botnet did because it was passed to them when their previous owners became liable for prosecution as adults, to sophisticated criminal organisations in Eastern Europe."

"China is noted for its targeted malware," says Goretsky's colleague David Harley, "but it is also the second most prolific sender of spam (first is the USA) and has a flourishing DDoS industry. Brazil and Russia both have long track records in the development of banking trojans. Russia probably has the lead in developer resources, with such goodies as Zeus malware and innumerable exploit packs."

Fighting back

The lifecycle of a botnet is now well understood, but how to beat them for good isn't quite so well defined.

"Once a botnet command and control server is created, botnet distributors just have to get their malicious code on a host," says Webroot's Jeff Horne. "They might infect victims' computers with exploit kits on drive-by download sites, email attachments, or use social engineering techniques.

"Once infected, the victims' computers register themselves with the C&C servers for constant communication, or check in to the server at regular intervals for new instructions, code, or to send information to the server, like keyboard logs, passwords, credit card information…"

Once established, waves of spam sent out by the botmaster himself and pointing to specially infected websites recruit more zombies and so the botnet grows – but it also draws attention, and an arms race develops between the botnet's writer and the antivirus companies.

Keeping the botnet's malware up to date isn't difficult, even for a non-coder, as BullGuard CTO Claus Villumsen explains: "The botnet master pays around $250 to have a new virus created, and an additional $25 a month to keep it upgraded, to try to avoid detection by virus scanners."

And with so many people still not running up-to-date antivirus software, as the botnet grows, it becomes clear that the best thing to do is track down the botnet and disconnect its lines of command.

"[It's done by] taking out the command and control elements of botnets by targeting their servers," says Catalin Cosoi. "This is not an easy task since most botnets have several C&C servers and they all have the possibility to update their code, like any other software product. In order to be successful, you have to take down all the C&Cs at the same time."

"Finding [the C&C servers] is the difficult thing," agrees Security Active's Dale Pearson. "They're all in private communities, so part of the battle is getting yourself immersed in that scene." However, even if you can take all of a botnet's C&C servers permanently offline, the army of zombies remains, regularly phoning home.

"The Mariposa framework had infected nearly 13 million machines and that framework is still alive," says Rik Ferguson. "The fact that the guys were arrested didn't take the botnet out."

The ISP issue

The one aspect of the botnet crisis we haven't covered is the role the ISPs might play. Surely they can break botnets by simply denying them bandwidth?

"There's a few things they could attempt to do," says Pearson. "They can use packet filtering software to identify when a botnet is running across their network and locate the zombie computers. The way to kill a botnet is to disconnect the machines, but that's going to annoy their customers. They can also throttle [outgoing mail] traffic if it's being used for phishing and spam, but again that impacts on their own users."

Another problem for ISPs is that botmasters don't tend to rent out the full power of their creations all at once. Using their full power at one time draws too much attention from both the ISPs and the botnet hunters, as David Emm explains.

"We're beginning to see [botnets] used as a rapier, rather than a blunderbuss, for activity, so it makes it difficult for ISPs to see what activity there is without the help of the industry. There are industry initiatives that are trying to work on these issues. The Conficker working group is possibly the best known of these."

ISPs, security companies, the authorities and perhaps even reformed hackers working together is the best way of fighting the botnet menace, but does this mean lazy home users can carry on without proper protection?

"In terms of countermeasures, detection of malware is a significant part of the process, but it's just one layer," says ESET's David Harley. "We work with other groups such as law enforcement, coalitions like the Conficker Working Group, and some rather more shadowy groups that don't appreciate the glare of publicity – we know the bad guys watch us as carefully as we watch them."