What is net neutrality and why does it matter?

Net neutrality definition is changing in 2014 due to new rules

Internet content is no longer treated equally in 2014, as the definition of net neutrality is changing with new Federal Communications Commission rules made public today.

The FCC's five commissioners voted 3-2 to seek public comment on "fast lanes" that would allow your internet service providers to greedily charge popular online services to connect to you at higher speeds.

This "paid prioritization" directly contrasts with the original intent of net neutrality, which was meant to keep ISPs from discriminating against or charging more for specific types of data.

Comcast, Verizon, Time Warner, AT&T and other broadband providers favor charging for "fast lanes." Big sites like Netflix, Google, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft, Dropbox and Yahoo naturally oppose it.

It's a problem for these online services that will have to pay new fees, entrepreneurs who can't, open internet advocates who saw this coming and the mostly unaware internet population who will ultimately foot the bill.

Examples of why this matters to you

Cable companies stand accused of deliberately and dramatically slowing down streaming sites like Netflix to their subscribers until Netflix pays them a fee for faster access to their customers.

This bullying tactic worked even though it's largely viewed as double dipping by cable operators.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

ISPs are receiving money from their subscribers to access the internet, including Netflix. Now they're receiving money from Netflix to access those same customers.

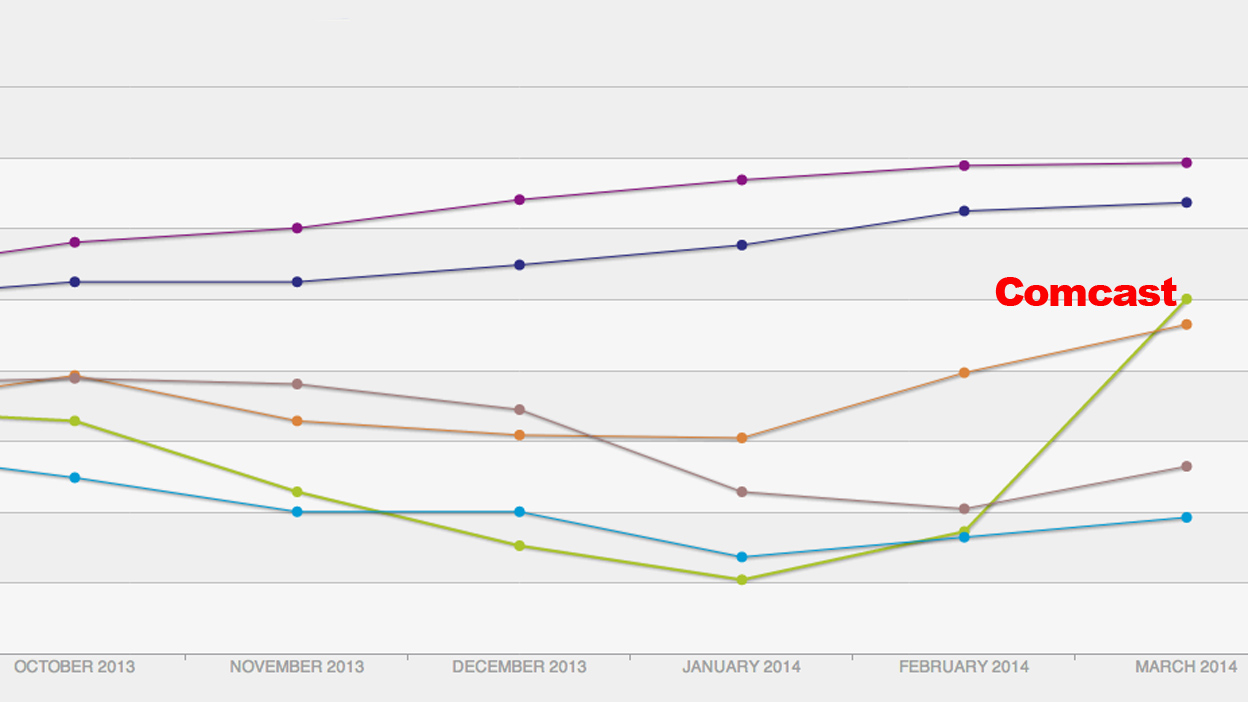

Comcast successfully received this ransom-like payment three months ago and only then did its Netflix speeds increase by 65%. Terms were undisclosed.

Verizon FiOS subscribers should see the same happen now that it has entered into a pact with the popular movie streaming for direct access. Netflix says it's unwillingly making these deals.

AT&T reportedly wants to start charging Netflix for this faster access to its U-verse subscribers, and Time Warner may end up being a part of Comcast.

Maybe not by coincidence, when Netflix agreed to pay off Comcast, low-and-behold, Time Warner's slow Netflix speeds increased too.

Netflix has already passed the bill onto new customers, though current subscribers get a two-year reprieve. Expect more charges to come down the narrowing pipe if this continues.

Here's where YOU pay... again

Cable providers are determined not just to reap money from consumers' choice of Netflix, but to be content providers themselves. Throttling Netflix speeds actually helps them do just that.

There's a fear in the cable industry that services like Netflix threaten to turn their business model into a "dumb pipe" like that of a telecom carrier.

ISPs don't mind creating a "pay to play" internet in violation of the original intent of net neutrality to stay relevant and squeeze out rival content providers.

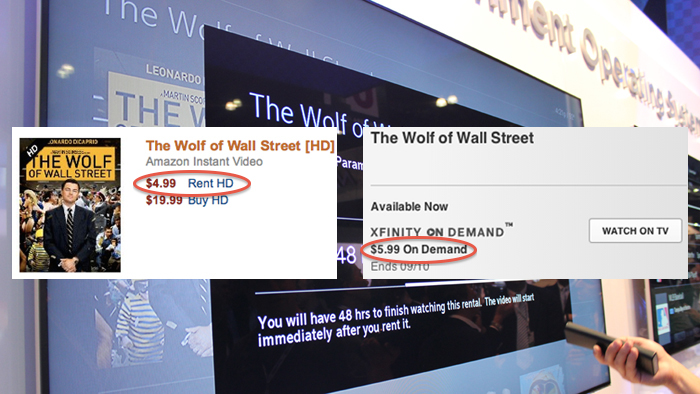

Comcast, for example, stands accused of a such a violation on the Xbox 360. Its Xfinity app streamed movie and TV content without counting toward internet usage when Netflix did.

All of a sudden, Comcast customers with data caps had an incentive to go use Comcast's on-demand video service instead of Netflix or any other data-eating service.

On top of that, when it comes to on-demand movies, Comcast likes to charge more money for its on-demand service. The Wolf of Wall Street currently costs $4.99 in HD through Amazon Instant Video, while Comcast wants $5.99 for the same HD video.

Where will these prices go but up without meaningful competition on a level playing ground?

Here's where entrepreneurs pay

At CES 2014 in January, AT&T introduced its "beneficial" AT&T Sponsored Data that didn't charge you for data being used when app creators foot the bill.

That sounded like a great idea to some in the audience, but others at AT&T's press conference saw right through it: if you have money, you can get an unfair advantage with AT&T customers.

That's unfair to the garage-based app developer with a legitimately innovative idea. The next Snapchat could easily be overshadowed by a deep-pocketed copycat like Facebook's inferior Poke app if it were too slow or counted against your data plan.

Facebook would have the money to copy and compete, but two Stanford University students with an original idea would not.