How to get secret service grade security

You could be forgiven for thinking that spying is all about midnight parachute drops, Aston Martins and vodka martinis – shaken, not stirred. However, when you strip away all the fiction, spying can be reduced to one word: information.

Espionage is all about acquiring information, keeping it safe and transferring it securely. This makes spies and spying a valuable learning ground for anybody who takes PC and internet security seriously.

In this age of high-speed broadband and information overload, you might expect setting up a secure communications channel to be easy. You'd be wrong. Just look at the Russian agents – coyly dubbed 'illegals' by the FBI – who were unmasked in America this summer.

They all had rock-solid cover stories, wads of cash at their disposal and access to cutting-edge spy technology, yet they were unable to keep their messages safe from American counter-espionage teams. We can all become safer surfers by understanding the techniques and, more importantly, the errors made by real life spies.

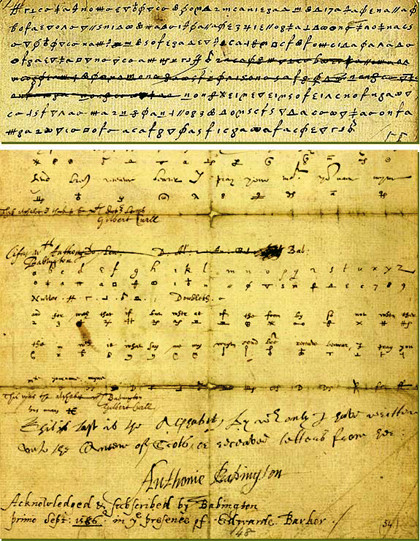

Ciphers, for example, have been the mainstay of espionage for centuries. A cipher makes information useless unless you know how it works.

When in Rome

Julius Caesar is often cited as the first to use a mathematically-based system of obfuscation. His cipher system was simple: each letter in the alphabet was shifted forward a fixed number of places. A Caesar shift of three would turn 'A' into 'D' and 'PC Plus magazine' into 'SF SOXV PDJDCLQH'.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Even in Caesar's day, such a cipher probably wouldn't fox many people for long. Such shifts can now be solved in the blink of an eye, but that doesn't mean ciphers should be discounted. Indeed, modern ciphers have evolved to a point where they would take so long to solve that it's not practical to break them.

Practically speaking, we should all use ciphers to encrypt sensitive data. A good choice for field agents is the free, open source TrueCrypt for Windows and Linux machines. This package uses some of the strongest freely available encryption algorithms, such as AES-256, the 448-bit Blowfish, CAST5 and Triple DES.

To give you an idea of its resilience, hard drives protected by TrueCrypt and belonging to jailed Brazilian banker Daniel Dantas were handed to the FBI for decryption in 2009. After four months of subjecting the software to intense attacks, the FBI gave up and returned the drives.

TrueCrypt isn't just useful for creating a virtual encrypted disc on your computer; it can also protect portable drives. This makes it ideal for 'brush passes' – a way of quickly handing over information as one spy walks past another in a public place. The process used to involve microfilm, but now a high-capacity USB key is the preferred medium – possibly why the FBI also calls brush passes 'flash meetings'.

A TrueCrypt USB drive has several layers of security. When set up properly, a TrueCrypt partition appears to consist of random data. Even if someone forces you to reveal the password (damn Jack Bauer and his rusty pliers!), you can create a partition to include a further hidden volume, or even an entire hidden operating system, containing sensitive information.

Take care when encrypting your files though, warns Steven Bellovin, Professor of Computer Science at Columbia University in New York. "Commercial cryptography software is so difficult to use that even experts find it challenging," he says. "Even really sophisticated people can get some subtle things wrong, and newcomers are likely to get a lot more wrong." Such as leaving the password for your encryption system written on a piece of paper at home for the FBI to discover, as demonstrated by clumsy illegal Richard Murphy.

Wireless networks

Even brief physical interaction has risks. If either spy is under surveillance, they risk exposing more of their network. A 21st century twist on the brush pass, then, is the wireless flash meet.

In New York, Anna Chapman, one of the Russian illegals, would hang out at a cafe or book shop with a laptop and create an ad-hoc Wi-Fi network: a private hotspot that requires neither a router nor an internet connection. A Russian government official carrying a smartphone would then approach the vicinity, join the network and exchange data as zip files. The spy handler never entered the building, and once completed the meeting while driving past in a minivan.

Wireless networks have their own problems, though. All wireless devices have a unique registration number, or Media Access Control (MAC) address, which is broadcast during a Wi-Fi data transfer. In the case of Anna Chapman, US law enforcement agents were able to divine her laptop's MAC address. This enabled them draw up a charge sheet showing that she'd visited certain places and joined ad-hoc networks, and sniff packets sent from her laptop in busy public network areas such as coffee shops.

If you're paranoid, you could change your network adaptor's MAC address. The 12-digit hexadecimal code is sometimes stored in an EPROM, which can be altered. Poke around the internet and you'll also find programs that enable you to spoof MAC addresses.

What can we learn from all this? Never, under any circumstances, send anything of importance over a public network. There are too many points of failure: the passage of data between your laptop and the network's access point, the access point itself, and the traffic between the access point and the internet.