Complaining about things used to be simple: you'd craft a furious letter full of dire threats to get your problem off your chest, and your target would promptly throw it in the bin to get it off his desk.

Now, though, the balance of power has shifted in your direction. Social media and social networks can create storms strong enough to unseat even the toughest MP or MD, expose the unspeakable and bring the bad guys to book.

But there's more to social media campaigns than just typing out a quick tweet and waiting for the world to notice: you need to have the right message, in the right place, at the right time.

To begin, it's always worth being friendly. If you're unhappy with a company, it's a good idea to seek them out on Twitter or Facebook before bringing out the big guns.

Paul Curry is a social channel manager with The Viral Factory, the multi-award-winning agency Ford, Samsung, Diesel and Levi's call when they want a viral marketing campaign, and as he points out, many firms are ready and waiting to read your tweets.

"Large companies with PR departments will have social media channels you can talk to, and more often than not they have the power to rectify small personal complaints," he says. For example, you can talk to O2 about mobile phone problems at www.twitter.com/o2, speak to BT at www.twitter.com/btcare, discuss travel plans with EasyJet at www.twitter.com/easyjetcare, or try to make sense of timetables at www.twitter.com/virgintrains.

If that doesn't work, you can turn to blogs such as Consumerist and forums such as Money Saving Expert. These are excellent sources of information, ranging from contact numbers or addresses for what Paul Curry calls "secretive upper-level support departments" to what to do when a firm won't honour its price promise. "The internet has become a very efficient powerhouse for talking to The Man," Curry notes.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

That's all well and good for any minor disputes you may be having with a company, but what if you're trying to achieve something bigger – telling the world about dangerous products, for example, or attempting to change a giant corporation's behaviour? "You're going to need a bigger boat," Curry says.

Oil on troubled waters

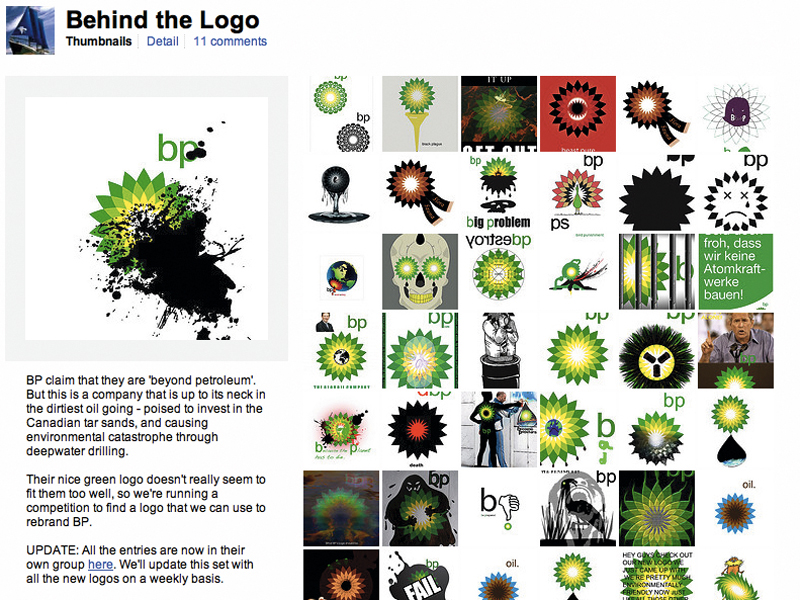

As BP tried to battle an enormous oil spill in June, a fake BP Twitter account started generating serious traffic. Using the @BPGlobalPR account, 'Leroy Stick' posted messages designed to embarrass the company, and the fake account soon generated more traffic than the official BP one.

By selling T-shirts with a parody of the BP logo, @BPGlobalPR has so far generated $10,000 for charity. "I started @BPGlobalPR because the oil spill had been going on for almost a month and all BP had to offer were bullshit PR statements,"

Stick explained in, ironically, a PR statement. "I started off just making jokes at their expense with a few friends, but now it has turned into something of a movement."

The success of @BPGlobalPR was down to serendipity, being in the right place at the right time. So how do you ensure that it's your message that's in the right place, that it's the one the internet picks up and runs with?

"A campaign has to be good enough to be re-shared," Curry says. It sounds obvious, but many would-be viral campaigns don't get off the ground because they're not funny, or relevant, or interesting.

"It's very easy to get angry and type a huge email out to all your friends, but chances are it won't be interesting to them," Curry says. "People are by nature selfish creatures, and unless they are sympathetic to your cause, or amused, then they won't spread the content on."

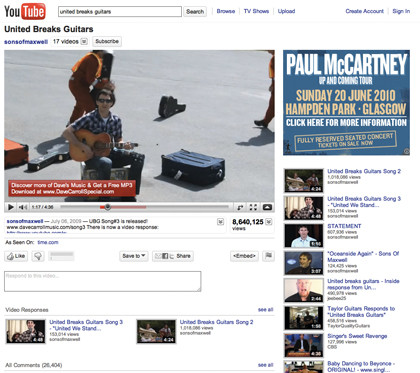

That means you need to carefully consider your medium. Posting "I don't like Ryanair very much" on Twitter, Facebook or a blog isn't going to catch anyone's imagination. Put it in a song and make a video with dancing cats and you're looking at a YouTube hit.

SING-A-SONG: A bit of talent goes a long way – the United Breaks Guitars song has achieved more than eight million views so far

For more serious campaigns, you need to develop a message that will resonate with people and that they will pass on. Standard PR tactics are yours to play with – a 20-page exposé of corporate misbehaviour won't be forwarded in the way photos of cute, oil-soaked animals would be. If you're a prolific social network user already, have a look at your profile and the things you've shared, posted or tweeted. What made you want to pass them along?

Spreading the word

No matter what message you're trying to convey, it's important to decide what you want to achieve from the outset.

When Twitter users posted everyday annoyances under the tag #nickcleggsfault, they were taking the mickey out of right-wing newspapers; when students slagged off HSBC on Facebook, they were lobbying the firm to change its overdraft policies for graduate accounts. If you don't know what you're trying to do, you won't know the best medium to use or the best places in which to promote your message.

The next step is to ensure that your message is seen by – and passed on by – the right people. If you already know the right people then that's a big help, because people with a public profile have a ready-made audience.

John Winsor is an influential marketer and a successful advertising agency boss, so when his eight-year-old son's scribbled aeroplane designs didn't excite Boeing, his publication of their standard 'get lost' letter circulated widely, ultimately reaching the pages of the New York Times.

Similarly, when director Kevin Smith told his 1.6 million Twitter followers that Southwest Airlines deemed him "too fat to fly", the airline was soon on the receiving end of his fans' outrage. Seeds of change Assuming that you're not an influential marketing guru or a cult film director, you need to carry out viral 'seeding'.

Seeding is the process of getting a campaign to key influencers, the people whose support will give your campaign real momentum. The first thing to do is find out whether people are already discussing something directly relevant to your campaign.

RAPID RISE: Trick cyclist Danny MacAskill became famous overnight when his YouTube clip got 350,000 views in 40 hours

If they are, joining in their conversation is a very effective way to get your voice heard. The details differ by network. Twitter users use hashtags (labels that indicate a tweet is part of a particular topic), while Facebook users have Groups and Pages, which are easily found via the search box.

It's best to get familiar with what they are before trying to make use of them yourself – you don't want to get on the wrong side of the people you want to incite against your target, or at best you'll find yourself being ignored.

Finally, you should try to get your message directly to people with influence. If you're a fairly active social network user, you'll have plenty of connections, and the more people you're connected to, the more likely it is that your message will be seen by someone who knows someone influential.

For the real social giants, you'll probably need to reach out for help. Don't assume that you need someone such as Stephen Fry – although, of course, a mention in his Twitter feed won't do you any harm. Experts, bloggers and in some cases angry mums will fill in just as well if you target your message correctly.

Beware angry mums

As Paul Curry explains, angry parents have incredible power. "Groups such as Mumsnet are among the most influential," he says. "If they get wind of something that could potentially harm children, there's no stopping them."

That's something pushchair manufacturer Maclaren learnt the hard way last year, after recalling buggies in the US amid claims of amputated fingers – but not the same buggies in Britain. Worried parents whipped up an online storm, with blogs such as Mindful Mum providing email templates for parents to use. It took just three days for Maclaren to change its UK policy and recall the buggies.

That speed isn't unusual. When something goes viral, it does so very quickly. Daredevil cyclist Danny MacAskill went from obscurity to celebrity overnight when a clip of his stunts generated 350,000 views in its first 40 hours online; Dave Carroll's United Breaks Guitars music video achieved three million views in just ten days; and @BPGlobalPR gained 128 million followers in just 18 days.

Things are speeding up as well. According to research by TubeMogul, in 2008 the half-life of a YouTube video – that is, the time it takes for a clip to generate half of the views it will get in its entire life online – was 14 days. Today, it's six.

- 1

- 2

Current page: How to start a successful Twitter campaign

Next Page Choosing the right social networks