Despite the recent revolution in social networking, at heart we're still a very private nation. We enjoy the legal right not to have the government poke its nose into our lives without the say so of a judge, and certainly not without good reason.

From 2015, however, the UK government plans to listen in on all our online lives. That's the shock news coming from Whitehall as the coalition publishes plans to allow the security services to monitor details of our private electronic communications, and to mine the resulting mass of data for hidden connections that will apparently help them identify "criminals and terrorists".

This intelligence will be passed onto the UK's shadowy intelligence agencies, the police and a list of other, as yet undisclosed, interested parties.

There are concerns, as you might expect, from pressure groups: "The automatic recording and tracing of everything done online by anyone of almost all our communications and much of our personal lives - just in case it might come in useful to the authorities later - is beyond the dreams of any past totalitarian regime, and beyond the current capabilities of even the most oppressive states," says Guy Herbert of NO2ID.

His is not a lone voice; opposition from industry and even within the government is growing. Are we right to oppose the government's plans? To find out, we investigated why such a move is apparently needed, how terrorists currently communicate and how the security services plan to harvest and use our data in this exclusive report.

Slippery words

By the time of the last General Election in 2010, New Labour was trying to force us to all buy costly ID cards. It had also temporarily shelved a more controversial plan to monitor all our electronic communications after vocal opposition from pressure groups, as well as the Tories and Liberal Democrats.

It seemed for a while that the coalition government that emerged after New Labour's subsequent defeat were firmly on the side of privacy. Page 11 of the Coalition Agreement of May 2010 contains a statement pledging to "end the storage of internet and email records without good reason." A week later, deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg said in a speech that, "We won't hold your internet and email records when there is just no reason to do so."

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Apparently as good as their word, one of the first acts of the new government was to scrap ID cards, but according to the Open Rights Group, the same government was also drawing up plans to resurrect Labour's monitoring scheme.

As far back as July 2010, just two months after the coalition agreement and Mr Clegg's speech, the first inkling of the plan surfaced in an obscure Home Office discussion document (The PDF can be viewed here.). Not only that, but buried away in the government's Strategic Defence and Security Review of October 2010 is this statement: "We will introduce a programme to preserve the ability of the security, intelligence and law enforcement agencies to obtain communication data and to intercept communications within the appropriate legal framework."

This is the Communications Capabilities Development Programme (CCDP), and it expands upon the previous Labour government's plans to implement mass digital surveillance. Despite this, David Cameron still apparently denied claims of a snooping database during Prime Minister's Questions on 27 October 2010: "We are not considering a central Government database to store all communications information," he said, "and we shall be working with the Information Commissioner's Office on anything we do in that area."

Security Minister, James Brokenshire also went on record to calm fears: "We absolutely get the need for appropriate safeguards," he said, "and for appropriate protections to be put in place around any changes that might come forward." He went further: "What this is not is the previous government's plan of creating some sort of great big 'Big Brother' database. That is precisely not what this is looking at."

In April this year, Nick Clegg was still claiming total opposition, and said so in a TV interview. "I am totally opposed, totally opposed, to the idea of governments reading people's emails at will or creating a totally new central government database," he insisted. "The point is we're not doing any of that and I wouldn't allow us to do any of that. I am totally opposed as a Liberal Democrat and as someone who believes in people's privacy and civil liberties."

However, none of these assurances tell the true story of the government's plans for us all.

Coalition opposition

Hints of what lie in store for us come from figures openly opposed to the programme within the coalition itself. "Every email to your friends; every phone call to your wife; every status update your child puts online. The Government want to monitor the lot, by forcing internet firms to hand over the details to bureaucrats on request," says David Davis, Conservative MP for Haltemprice and Howden and former Foreign Office minister.

The central argument for CCDP, of course, is that to carry on detecting serious threats to the nation, GCHQ now needs to harvest data about private electronic communications on a massive scale. The listeners in Cheltenham will sift the 'who, what and where' of every electronic communication and pass the distilled intelligence on to interested parties within the mesh of UK security agencies for analysis of the underlying threats.

The data to be distilled will include pretty much everything that doesn't need an explicit warrant to be read, including the websites we visit and our search histories. Not only that, but social networking sites, such as Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter could also be ordered to provide information about their users.

It's not difficult to work out what information GCHQ will be able to extract from such a detailed view of us all, but the implications and capacity for miscarriages of justice are potentially immense if proper common sense isn't also applied, according to David Davis: "Of course governments should use the best tools at their disposal to tackle terrorism," he concedes.

"But we can do this under the current system. If they want to see all this information, they should be willing to put their case before a judge or magistrate. This will force them to focus on the real terrorists rather than turning Britain into a nation of suspects."

Clueless snooping

The whole idea of CCPD is "clueless", according to Ross Anderson. He's the Professor of Security Engineering at the University of Cambridge's Computer Laboratory. Anderson was speaking in April this year at the Scrambling for Safety 2012 conference held at the London School of Economics.

He was by no means the only critic of the government's plans. Sir Chris Fox, ex-head of the Association of Chief Police Officers, also spoke at the conference, claiming that CCDP "won't catch top-level criminals and terrorists." Anyone that is smart enough to form an organised crime ring or terrorist cell will simply find other more covert methods of communicating, he said.

Respected security researchers have also criticised CCDP for the apparent ease with which net-savvy terrorists could circumvent it. "If national governments and law enforcement organisations truly believe that online criminals and international terrorists don't know how to hide their online traces, then we have a bigger problem than we thought - sending an encrypted email with spoofed sender address from an Internet café is only lesson one."

So says Rik Ferguson, of Trend Micro. Current EU legislation means that your mobile phone network already collects extensive data about your calls and texts (though not their content). This data is stored for between six months and two years in case the police or security forces need it to support a conviction.

In future, this will form part of the mass of data processed by CCDP. However, it's the detail with which the security services will be able to snoop on us that comes as the biggest shock.

For example, O2 says in its privacy policy that it collects: "Phone numbers and/or email addresses of calls, texts, MMS, emails and other communications made and received by you and the date, duration, time and cost of such communications, your searching, browsing history (including websites you visit) and location data, internet PC location for broadband, address location for billing, delivery, installation or as provided by individual, phone location." This information can then be shared with third parties "where required by law, regulation or legal proceedings."

On the other hand, ISPs are not happy about the government's mass monitoring plans. Many ISPs only collect basic statistics about network and use it to help them plan ahead and cope with times of peak demand. Where individual users abuse their broadband service, ISPs can identify and throttle back their traffic and even terminate their connection as per their end user agreements.

For ISPs, it appears that CCDP is an unwelcome addition to their networks, because it will mean large amounts of work to implement and maintain. "What we do know," says Gus Hosein of Privacy International, "is that there have been secret briefings to MPs designed to scare them into compliance, and secret briefings to industry that were originally designed to calm their fears but in fact have only served to increase their outrage."

To understand how difficult it is to spot terrorists in a sea of 60 million people all enthusiastically chattering in cyberspace, it's necessary to understand something of how terrorists currently use the internet to communicate.

Jihadi73 killed you

Terrorists and serious, organised criminals use a variety of communications methods designed to avoid capture. However, the most dangerous terrorists of the type trained in Al-Qaeda-sponsored camps know that the authorities can already follow and otherwise monitor them under existing laws.

To continue to plot their evil deeds, they must find increasingly novel ways of passing information between each other. Massively multiplayer online role-playing (MMORPGs) and First person shooter (FPS) videogames offer unique opportunities for covert communications. Members of a conspiracy can easily purchase any number of videogames and meet up in a randomly chosen game to chat privately.

Security analysts at The Rand Corporation have also noted a disturbing development: Multiplayer videogames themselves can be a recruiting ground for extremists. The team combat nature of many such games and the popularity of player guilds in MMORPGs and clans or squads in FPS games naturally leads to close bonds forming between strangers. Simple games can lead to sharing of ideology and face-to-face meetings with willing players, it seems.

In a report (pages 13 to 15) the Rand boffins also claim that the open nature of games like Call of Duty make them potentially easy for the security services to monitor. The publishers of such videogames are also subject to current security legislation.

Another potential technique for communication is the 'dead letter box'. In many spy films, agents use these as a safe place to physically drop off and pick up secret messages. In the age of the internet, however, this technique has moved into cyberspace. Instead of sending incriminating emails, criminals can simply share login credentials for a single web mail account.

Person A logs into the account, writes a message for person B and saves it to the drafts folder. Person B then logs in, reads the message, leaves his reply and deletes the original message. Person A can then log in and read the reply. No mail is sent, so no headers are captured by CCDP.

The disadvantage is that if the security services are already monitoring the account, they can read the communication flowing between the two suspects, even if this doesn't reveal any extra email addresses to monitor.

'Burner' phones

In some of the most deprived areas of the UK during the mid 1990s, mobile phone shops began to thrive. This was despite handsets and calling charges still being prohibitively high for most people. It turns out that drug dealers were buying phones and using them to stay in touch with clients and upstream suppliers. If the police became aware of the existence of individual phones, they could simply be destroyed or 'burned'.

Because of how deeply mobile phone shops sometimes check personal details when registering a new handset, burners are still used. When glamorous Russian spy Anna Chapman realised that she had been unmasked in the US in 2010, she immediately bought a new phone under an assumed name, reportedly registering it to an address in "Fake Street".

Using a real identity when buying a burner can be as simple as rifling through your bins for utility bills and other forms of ID. This highlights the need to shred everything that can identify you before throwing it away.

Ultimately, avoiding modern communication techniques is the only safe way of staying out of the government's digital net. Talking face-to-face, passing messages through an intermediary and other techniques are called field craft. Public places, random bars, loud clubs and public gatherings are all used by criminals keen to avoid capture, but being public, these can also be infiltrated by the security services in the pursuit of evidence.

The security services can also obtain extensive warrants to bug buildings, and they even employ lip readers to analyse and transcribe footage of covert conversations.

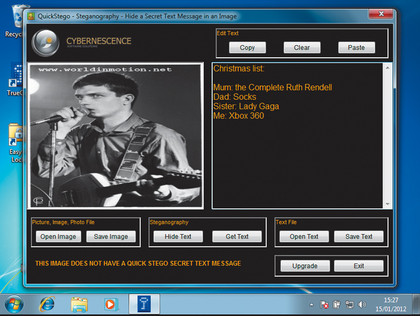

There are also techniques that people have used for decades to hide messages in plain sight, such as steganography. Someone might hide a secret message in a JPG file by very subtly manipulating the values of individual pixels spread in a regular pattern throughout the file. To the casual observer, changes to the image are undetectable, but the right software, such as QuickStego, can store and retrieve the original message.

In its 2007 report (page 31), the Rand Corporation said that subversives currently do not tend to use steganography much, but that it would be prudent to monitor the technology in the face of growing threats. As this was a public report, it's equally prudent to also assume that the security services now actively check for messages encoded in image files.

Recognition cheats

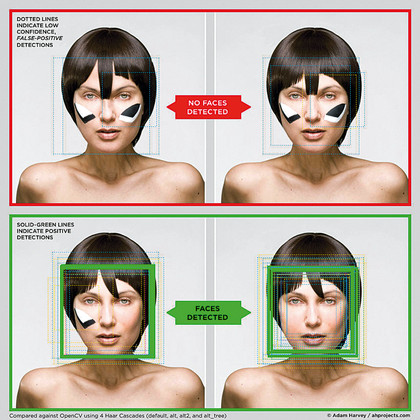

So, things are getting tighter for terrorists, but ingenuity knows no bounds. The widespread use of software that recognises faces in crowds is troublesome for targets trying to remain undetected in built-up areas, but adopting outlandish makeup and haircuts could be one way to fool it.

For his Masters thesis in the Interactive Telecommunications Programme at New York University, Adam Harvey has developed a technique to camouflage people from Big Brother. Called CV Dazzle, the technique is similar to the bold asymmetrical camouflage found on battleships during World War II, designed to break up lines and confuse the enemy.

Sunglasses, moustaches and beards are easily taken into account in facial recognition, as are hats and hoodies. The software identifies faces from their symmetrical features (two eyes, nose, mouth placement, and so on in the usual configuration). Harvey's idea is to break up these recognisable features.

To do so, he experimented with asymmetrical fringes that flop into the eyes and bold streaks of black and white makeup across the cheeks. Provided the streaks are of different designs, it seem that the artificial intelligence becomes confused and fails to map out the face's features properly.

Harvey's CV Dazzle website gives plenty of examples, only leaving the problem of standing out in a crowd to any casual human observer. Unless, of course, it becomes a fashion statement of a new web-savvy generation keen to avoid detection by the authorities.