Going mobile

SMART CAMERAS: Google Goggles' visual search is a taste of things to come

Our 3G phone networks weren't built with data in mind, and if you've ever struggled to download an email on a five-bar 3G signal, you'll know that networks are already struggling to cope. "I suspect that network operators have been caught by surprise by the increase in demand,"

Davies says, pointing out that operators "work on a two-year planning horizon, so if they do come across unexpected capacity problems it isn't always possible to do a quick fix."

Two developments should help: freeing up the 800MHz frequency band when analogue TV signals are switched off in 2012, and network operators upgrading to LTE (Long Term Evolution), often dubbed 4G. LTE won't be widespread for several years though, so we're stuck with 3G until at least 2015.

There is another option: HSPA+ (High Speed Packet Access Plus) - an upgrade to existing 3G networks that can, in theory, deliver 42Mbps download speeds. It isn't as solid or as fast as LTE, but several UK operators are considering it.

With demand for mobile data soaring, a crunch is coming. Network planners already report congestion issues, but these aren't spread equally: some congestion is in specific locations, other congestion at particular times of day. In a survey commissioned by telecoms billing firm Amdocs, 20 per cent of operators reported 'severe overload' at times, and just 37 per cent said their networks are running fine. 40 per cent of operators said 'bandwidth hogs' were contributing to problems. Expect to start paying more for mobile access, or more limits on what you can and can't do.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

"O2 is forecasting a hundredfold increase in bandwidth requirements over the next few years… the figures don't stack up," Davies says. "Mobile operators have to raise the cash to pay for the new infrastructure and so they are looking at innovative pricing mechanisms. This hasn't arrived in the public domain yet, but we are being warmed up for it."

One such mechanism could be Dynamic Spectrum Access, a kind of electronic auction where your phone bids for bandwidth it needs. The good news is that the crunch isn't imminent, because the real bandwidth hogs are 3G dongles rather than smartphones.

"I don't think that mobile apps will drive the need for the same bandwidth as fixed line in this timeframe, although we should never say never," Davies says. "My HTC Desire HD already supports 720p HD video, but the industry needs to sort out battery life before we will see serious high speed usage from handsets."

Once that happens, mobile bandwidth is likely to become a premium product. If you want a fast, lag-free connection at peak times or in congested areas, you'll have to pay more for it.

Bye bye browser?

It seems backwards, but just as software moves online, the browser itself is becoming less important. Increasingly, data is delivered to and received from a range of apps on a myriad of devices, which all have a bit of browser built in.

You can see that happening in social networking. Much of Twitter, Facebook and Flickr's traffic comes from applications: mobile phone apps, desktop software with social media export options, stand-alone photo uploaders, desktop widgets, browser-based aggregators that combine multiple networks in a single browser window and so on.

It's a similar story with YouTube, which delivers video to the web, mobile phone browsers, televisions, and mobile phone and iPad apps, and which accepts uploads not just from the YouTube website, but from cameras, camcorders and games.

The key to these apps is the API, short for application programming interface. APIs are hooks that developers can use to get data from or put data into online services. For example, Twitter's API enables third-party applications to post to and get data from Twitter.

But the API is just part of the picture: the data also needs to be delivered in a format that means it's easy to use and easy to combine with other sources. Increasingly that means open standards such as HTML5.

HTML5 and Flash

Designing for the web used to be simple. If it was static, you built it in HTML and CSS. If it moved, you built it in Flash. Not any more. The emerging HTML5 standard does animation, video and effects too, and Apple for one believes that it's going to make Flash obsolete. Apple may be right.

HTML5 does many things that once required plugins or stand-alone software, including video, local storage and vector drawing - and unlike Flash, it's an open standard that produces search engine-friendly content.

HTML5 is far from finished and it'll be some time before it's as attractive to developers as Flash. It lacks the write-once run-anywhere appeal of Flash, because different browsers have implemented bits of HTML5 in different ways, and it lacks the excellent authoring tools that Adobe has spent years refining.

In the long term, however, we'd expect more and more content to be created in HTML5 rather than Flash, much of it using Adobe tools.

HTML5 has one particularly interesting trick up its sleeve: microdata. This enables designers to label content, and it's something Google already supports. Its Rich Snippets uses microdata to pull the relevant information about a website and display it in the search results. That information could be details of a restaurant's cooking style, the verdict of a review, contact details or anything else that can be expressed as text or a link.

This metadata is machine readable, and machine-readable metadata gets people like Tim Berners-Lee very excited. In 1999, he said: "I have a dream for the web [in which computers] become capable of analysing all the data on the web - the content, links, and transactions between people and computers… the day-to-day mechanisms of trade, bureaucracy and our daily lives will be handled by machines talking to machines."

Visions of the future

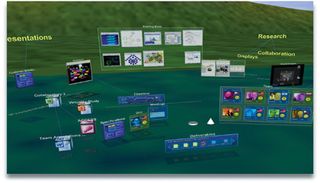

At Intel's Visual Computing Institute (VCI) in Saarbrueken, Germany, researchers are exploring what could be the next generation of interfaces by combining motion capture, photorealistic computer graphics and 3D navigation. Can we expect 3D interfaces in the near future?

FUTURE INTERFACES: Intel's Visual Computing Institute is experimenting with interfaces that mimic the real world

"The answer is a qualified yes," says Hans-Christian Hoppe, Co-director of Operations at the VCI, who admits that "in the late 1990s, VR arguably fell into the category of 'a solution looking for a problem', and unfortunately not a very elegant solution. One could draw a parallel with tablet devices," Hoppe continues.

"They have been around for many years, in many guises, but it was only when the user experience met expectations that the devices became successful." Hoppe says we're reaching that point with immersive interfaces.

"Hardware has indeed advanced, in particular for mobile devices. That isn't the key issue, however. Social networking has evolved from a fad to addressing people's needs… immersive virtual worlds are now able to look like a natural extension of the likes of Facebook - suddenly, all this technology might be useful."

"Pervasive network connectivity and performance are important, processing power and energy efficiency likewise, particularly on mobile devices," Hoppe says. But the technology needs to be matched with innovative thinking.

"All we have today are extensions of tried and trusted 2D interfaces," Hoppe says. "What is needed is a uniform way of interacting with a mixed 2D/3D environment that's easy to understand, convenient to use and that doesn't strain the human perception and motion senses."

We've been promised 3D internet before, but Intel's vision isn't blocky avatars but realistic, ray-traced images delivered in real time, and we're approaching the point where our hardware and networks are fast enough to deliver it.

Whether we'll want it remains to be seen, but when it comes to technology, having extra options to explore is rarely a bad thing.