The problem with free - you still gotta pay

Free content doesn't come cheap. So who's going to pay for it?

We're so used to the idea that everything online should be free that we don't even think about it.

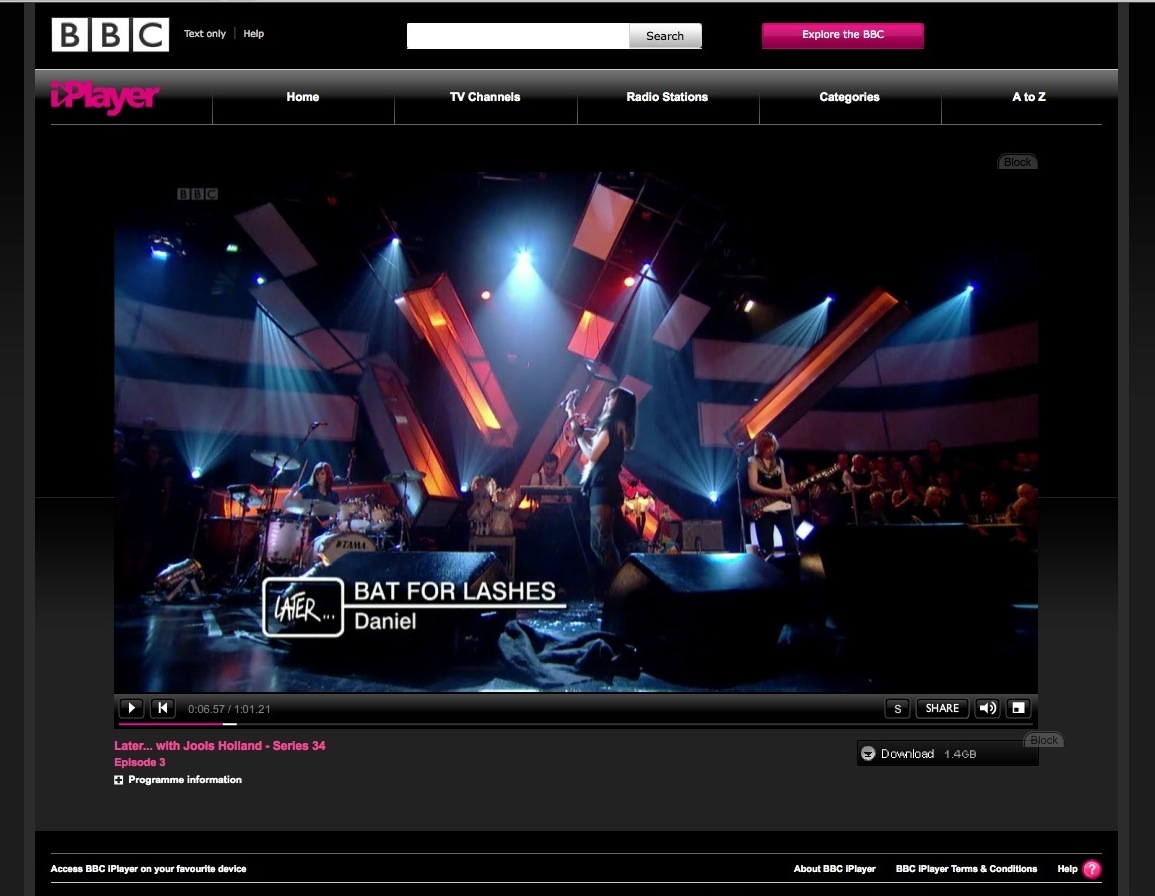

Of course the iPlayer should give us HD video for free. Of course Spotify should stream music for free. Websites? Free. News? Free. Video? Free. Software? Free.

There's only one problem. Free costs money, and there isn't enough of it.

Burn your money

Fancy setting up a rival to YouTube? Here's a better idea. Hire a skip, put your life savings into it and set it on fire. YouTube's popularity is costing it a fortune: according to analysts at Credit Suisse, it's going to lose $470 million this year.

If you're delivering copyrighted content such as music or video, you need to pay the copyright owners. In an interview with PaidContent, Steve Purdham of We7 says: "You're talking about roughly a penny a stream for on-demand streaming." Just covering the royalty payments would require ads to bring in £10 per 1,000 impressions, although that still wouldn't cover the other bills; Purdham says the actual income is between £1 and £12 per 1,000.

Royalties aren't a new-fangled, internet-only idea. Radio stations pay them, as do broadcasters and even libraries: an organisation called Public Lending Right (PLR) collects money from the government and dishes it out to the writers whose books we borrow.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Pros want to be paid

The reason sites have to pay royalties is because in most cases, people want professionally produced content - and professionals like to get paid.

When you watch Susan Boyle making Piers Morgan look evil on Britain's Got Talent you're watching the work of cameramen, sound engineers, lighting engineers, set designers, roadies, runners, researchers and so on.

There's an unspoken agreement between you and the broadcaster: It'll pay to make the programme, and you'll watch ads. The broadcaster then makes money from the ads and pays the programme makers (the BBC is different, of course: instead of ads, it has the licence fee).

It's the same with commercial radio. The radio station makes money from ads, and it pays royalties to the musicians.

YouTube is no different: it hosts the clip, and the ads are supposed to pay for the costs of hosting and streaming as well as the appropriate royalties. That's the theory. The reality is that the ads simply aren't bringing in enough cash.

As Slate reports, bandwidth costs YouTube $360 million per year, broadcast licenses are another $250 million and various other expenses bring the total cost to $700 million per year.

Ads only bring in $240 million, and the credit crunch is pushing rates down. Meanwhile YouTube's costs are skyrocketing: HD video needs five times the bandwidth of standard definition clips.

It's not just the so-called dinosaurs - the newspaper groups, the TV stations and the radio networks - that are bleeding red ink. If YouTube were a stand-alone company, it'd have gone bust ages ago.

Of course, not all firms have to pay the pros for content. User generated content is free, it's abundant and it's popular - whether it's Flickr photos, Twitter tweets or Facebook status updates.

Unfortunately, while you can get the content for free, actually doing something with it costs money. Lots of money. Slate estimates that Facebook spends a million dollars per month on electricity, half a million on bandwidth and two million a week on adding servers.

User generated content may be free, but it isn't cheap.

FREE CONTENT: User generated content is free, but hosting it costs - Facebook's electricity bill is $1 million per month

Writer, broadcaster, musician and kitchen gadget obsessive Carrie Marshall has been writing about tech since 1998, contributing sage advice and odd opinions to all kinds of magazines and websites as well as writing more than a dozen books. Her memoir, Carrie Kills A Man, is on sale now and her next book, about pop music, is out in 2025. She is the singer in Glaswegian rock band Unquiet Mind.