Safe, secure and speedy: that's the internet of 2020. In a decade's time, the web will be a very different place.

There will be no crime, no malware and no fake online banking sites. Latency won't be a problem. High-definition video will be smooth, and buffering will be a distant, nightmarish memory. And that's not all.

The internet will have grown dramatically, making room for a new generation of connected devices: cars, phones, TVs, everything. Super-fast speeds are the rule, not the exception.

To borrow a phrase, it just works. At least, that's what we hope the web will be like.

To make it happen, engineers merely need to rethink the way the internet works and change pretty much everything. What could be simpler?

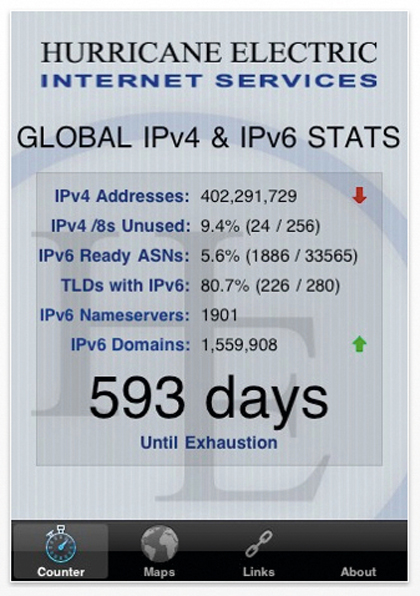

Some big changes are already in progress. The explosion of internet enabled devices means that we're running out of IP addresses even more quickly than expected: RIPE NCC's Managing Director Axel Pawlik noted in January that the pool of unassigned IPv4 addresses would run out as early as 2011. But the move to IPv6, which can handle around "a trillion trillion trillion" addresses – 3.4x1038 if you're feeling pedantic – is largely a software, not hardware, issue.

"In most cases it's very easy to reprogram connectivity software on a chip to ensure a device is IPv6 compatible," Pawlik says. But things aren't progressing as straightforwardly as you would think.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

"Despite the simplicity of ensuring compatibility, widespread IPv6 take-up has so far been slow, and many of the best known digital devices available today, including the iPhone, do not yet support the next generation of IP addressing," warns Pawlik.

That lack of urgency is disappearing fast, with big names like Google implementing IPv6 support, router firms embracing the new system and new operating systems – including Windows and OS X – supporting it.

If we're late embracing IPv6, the internet won't grind to a halt – existing IP addresses will keep working – but as the European Commission reports, "the growth and also the capacity for innovation in IP-based networks would be hindered". The EU is pushing IPv6 hard, and it expects European ISPs and "the top 100 European sites" to be IPv6-enabled this year.

NOTHING ON TV?: Watch IPv4 addresses run out in real-time with the Hurricane Electric iPhone app

As a happy by-product of IPv6, widespread adoption will make the internet more secure too. The IPsec security protocol is a compulsory part of IPv6, which means all IPv6 communications can be encrypted and authenticated.

Route masters

We're using the internet in ways its creators couldn't possibly have imagined, from the rise of video to the sheer number of connected devices. We're constantly pushing the internet's capacity, stability and security, and inevitably cracks are beginning to show.

Aaron Falk is the Chair of the Internet Research Task Force (IRTF) and Engineering Lead with the Global Environment for Network Innovations (GENI). "There are many areas where the current architecture is straining to meet the needs of the users," he says.

"In particular, the areas of mobility, security, and network management were not well addressed in the original architecture, leading to a patchwork of mechanisms. The greatest concern is not so much that today's traffic is challenged but that the ad-hoc machinery being inserted into the network will inhibit future innovations. I worry about tomorrow's applications more than today's."

The IRTF is a technological trouble-shooter for internet architecture, as Falk explains: "The IRTF hosts research groups that work in areas 'adjacent' to the IETF (Internet Engineering Task Force). This can be pre-standards technologies, hard problems that emerge from the IETF or operations communities, technologies where the internet may be one of many possible communications strategies, or architectural issues."

He continues: "Sometimes research groups assist IETF working groups by bringing researcher expertise or otherwise 'pre-baking' technologies so they are ready for standardisation. For example, the Mobility Optimizations Research Group has been working on IP mobility solutions that feed into the MIPSHOP (Mobility for IP: Performance, Signalling and Handoff Optimization) working group for standardisation. Another example is the IRTF Research Group on Internet Congestion Control (ICCRG) which evaluates new congestion control proposals that arise in the IETF."

I dream of GENI

One of the problems with the current web is that it's too big and too important to muck around with. That's where GENI comes in. The Global Environment for Network Innovations is funded by the US National Science Foundation, and it's best described as a (serious) playground where new ideas can be tested out.

"GENI will support two major types of experiments," the organisation says. "Controlled and repeatable experiments, which will greatly help improve our scientific understanding of complex, large scale networks, and 'in the wild' trials of experimental services that ride atop or connect to today's internet and that engage large numbers of human participants.

"We're well underway on the second year of GENI prototyping, GENI Spiral 2," Falk says. "One of our more exciting activities is what we are calling 'meso-scale deployments' of virtualisable, programmable routers, switches, and WiMax base stations on 14 campuses and two national research backbone networks.

"Deployments like these are particularly exciting because they'll allow experimental applications and services built on GENI to directly reach real users on university campuses. Thus researchers will have the ability to build new services – perhaps incompatible with the current internet – and test them at-scale with real end-users."

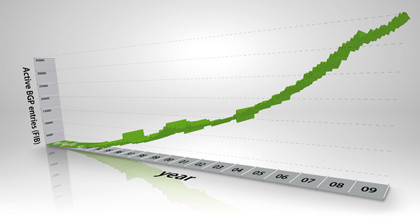

One area of concern is routing tables, which the net's backbone routers use to direct online traffic. The BGP (border gateway protocol) routing table has grown hugely, doubling in size between 2003 and 2009, and there are concerns that if the level of growth continues, router hardware won't be able to cope.

UP AND UP: The BGP routing table doubled in size between 2003 and 2009, and it's still getting bigger

The IRTF's Routing Research Group (RRG) is investigating alternatives, and its goal is to produce solid recommendations that the IETF can implement.

Another related program is Rochester Institute of Technology's Floating Cloud initiative, which hopes to address the problem of routing table growth by moving the routing tables from inside routers to network clouds. Initial testing took place on a dozen Linux boxes, and the next step is to try it on GENI.

GENI isn't the only initiative that the NSF is helping to fund. Its Future Internet Architectures (FIA) program is offering $30million to fund projects that will transform the net. As the NSF puts it: "Proposals should not focus on making the existing internet better through incremental changes, but rather should focus on designing comprehensive architectures that can meet the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century."

FIA is a continuation of FIND, the NSF's Future Internet Design project. FIND asked researchers to redesign the internet from scratch, and FIA will narrow around 50 FIND projects down to two, three or four serious contenders.