Lorelei’s story: how a 5-year-old crowd-sourced a robotic prosthetic

With help from her family and a whole lot of friendly strangers

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) is a rare condition that affects the nervous system and has about a 2% recovery rate. The starkness of a medical statistic like this is brutal, and even more so when it relates to the health of your own children, but this was what Bodo Hoenen and his family were facing in the summer of 2016 when their five-year-old daughter, Lorelei, was diagnosed with AFM.

The condition particularly affects the spinal column and in Lorelei’s case it had paralysed her left shoulder and left arm. “The prognosis was that the only thing that would help was occupational therapy and physiotherapy,” says Hoenen, “but looking at the results, back then, there were only two kids that had had any significant recovery…”

Hope was needed and it was sparked by a project the family saw in the hospital: “Researchers were strapping on an exoskeleton suit to paraplegic individuals and providing them the biofeedback with the suit,” recalls Hoenen. “They also provided visual feedback by adding a VR headset showing them the actual movement of the arms. With the headset, you would see yourself walking and then feel your body walking as the exoskeleton suit was moving your body and this would force the brain to think ‘Okay, I’m going to walk now’ and they would pick up those signals from the brain and translate them into messages to control the exosuit and VR.”

After consulting specialists, Hoenen theorised that instead of hooking sensors to the brain they needed to hook sensors directly to the biceps muscle in Lorelei’s arm: “We knew there were at least very weak signals going to the muscle and we were hoping to pick those up and hoping that forcing her to continue sending signals to her muscles would help that rehabilitation process.”

Hoenen knew that probably the best way to do this was to build some kind of robotic prosthetic arm, but he had a problem: he had no idea how to do it. That’s when he and Lorelei decided to ask the world. “We decided to leverage the collective intelligence of everyone around us,” says Hoenen.

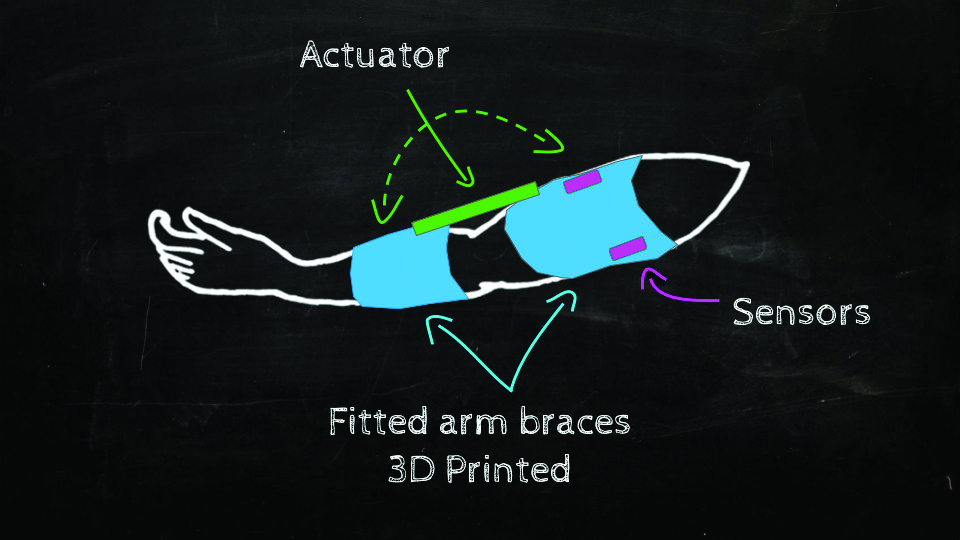

So, after sifting through all the information they could find and talking to other parents with children that had AFM, Bodo and Lorelei got to work with a simple first design – they wanted to 3D-print the braces and somehow acquire an actuator motor to help pull the arm up and down. But before they got too far into the project, they decided to record some videos to ask experts for help.

The response was “pleasantly surprising”, says Hoenen. Within a couple of weeks they’d had Actuonix donating actuators while, among many helpers, they’d received assistance from experts in battery tech and electronics from South Africa and Germany respectively, and had a full scan of Lorelei’s arm done. It wasn’t long before a prototype was made, followed by a 3D-printed sleeve in PLA.

Are you a pro? Subscribe to our newsletter

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

Signal problems

However, the biggest issue they faced was picking up the muscle signal from Lorelei’s arm. They discovered that it was very difficult to filter and normalise the signal and set a threshold that triggered the actuator. Hoenen found there was very little difference in the signal between when her arm was at rest or active. As they tried to set a threshold, they also noticed that the actuator could be triggered by a finger twitch or even Lorelei’s heart, so they put out another video asking for help.

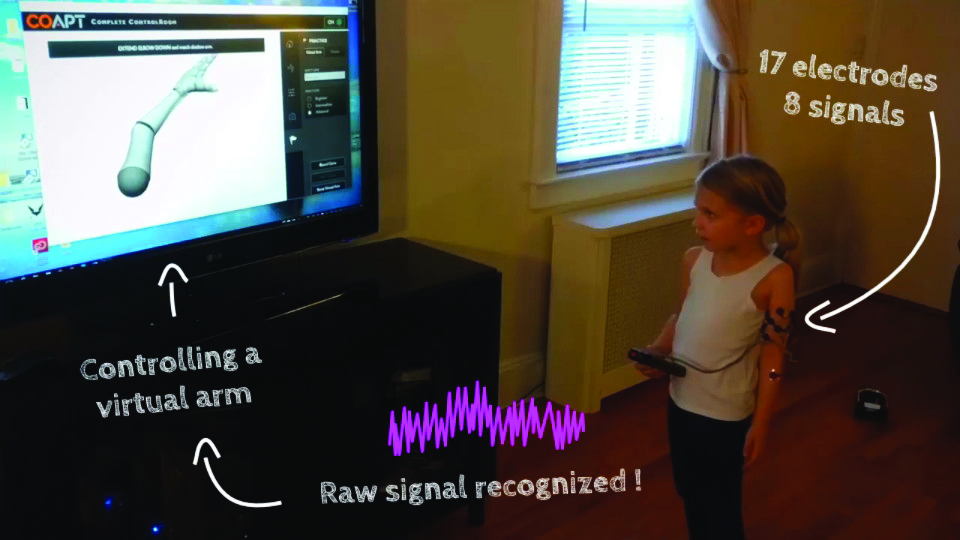

Hoenen pitched the idea that the raw signal could be run through machine learning or pattern recognition software to track down a unique signal. Soon after posting their video, they came across a firm called Coapt that uses pattern recognition software to help amputees use prosthetic limbs. The company has a proprietary system that uses 17 sensors to track the muscle signals. The software translates the signals it finds into corresponding movements on a virtual arm. Coapt gave the family an evaluation unit to enable Lorelei to practise and pick up the arm signals, which meant Hoenen could finally create a working model.

While some manufacturers were incredibly generous, Hoenen says he encountered a surprising amount of negativity from others: “A lot of them kept mentioning ‘is this FDA approved?’ [...] From my perspective, I don’t care. This is about my daughter, I want this solution to work. This stuff that you’ve got costs $50,000. I just can’t afford that and the technology that you have isn’t all that clever, so why don’t we open-source this and expedite the innovation that happens with what we’ve got and this will create a better world for all of us including your business model?” Unfortunately, many medical manufacturers aren’t willing to even consider experimenting with open models yet. “Open innovation drives innovation exponentially [compared to] closed, but they failed to really grasp that,” says Hoenen.

In January of this year, Lorelei came up to her parents and said, "Hey look what I can do," and was able to move her arm up and down unassisted. Since then she hasn’t needed to use the prosthetic and while Hoenen says it’s not something he wants to take further himself, he’s helping other parents and trying to tackle “some of the core challenges still to overcome.” These include developing bridge software between a system of 17 electrodes and the device, the Raspberry Pi in this instance, and getting the correct build for the arm sleeve that houses the electrodes.

Talking about the experience, Hoenen is careful to downplay the technology. He’s also pragmatic over whether the arm made that much of a difference to Lorelei’s recovery: “At the moment, we only have a sample size of one,” he concedes. At Medicine X Stanford in September, Hoenen preferred to describe the experience as a story of “tangible hope, where we would have been spectators without this project”. However, other parents who have children diagnosed with AFM are using the project to build robotic prosthetics and challenging that 2% recovery rate.

Bodo and Lorelei's project is documented and open-sourced on www.ourkidscandoanything.com with videos of the journey, guides for building the arm itself and more details of the key remaining challenges.

(This feature was first published in issue 184 of Linux User & Developer).

Chris Thornett is the Technology Content Manager at onebite, editor, writer and freelance tech journalist covering Linux and open source. Former editor of Linux User and Developer magazine.