Mystery of Mars' ancient trenches might have finally been solved

Apparently, Mars' crater lakes couldn't hold it in any longer

The deep trenches on the surface of Mars have long been one of the planet's more fascinating mysteries, but now a team of researchers might have identified what caused the deep river valleys that have perplexed scientists for decades – and the answer is about as violent as the planet's namesake.

On Earth, river erosion is typically a gradual process that takes place over centuries or even millions of years, scoring the surface soil bit by tiny bit; but on Mars, a more catastrophic process might have been far more common.

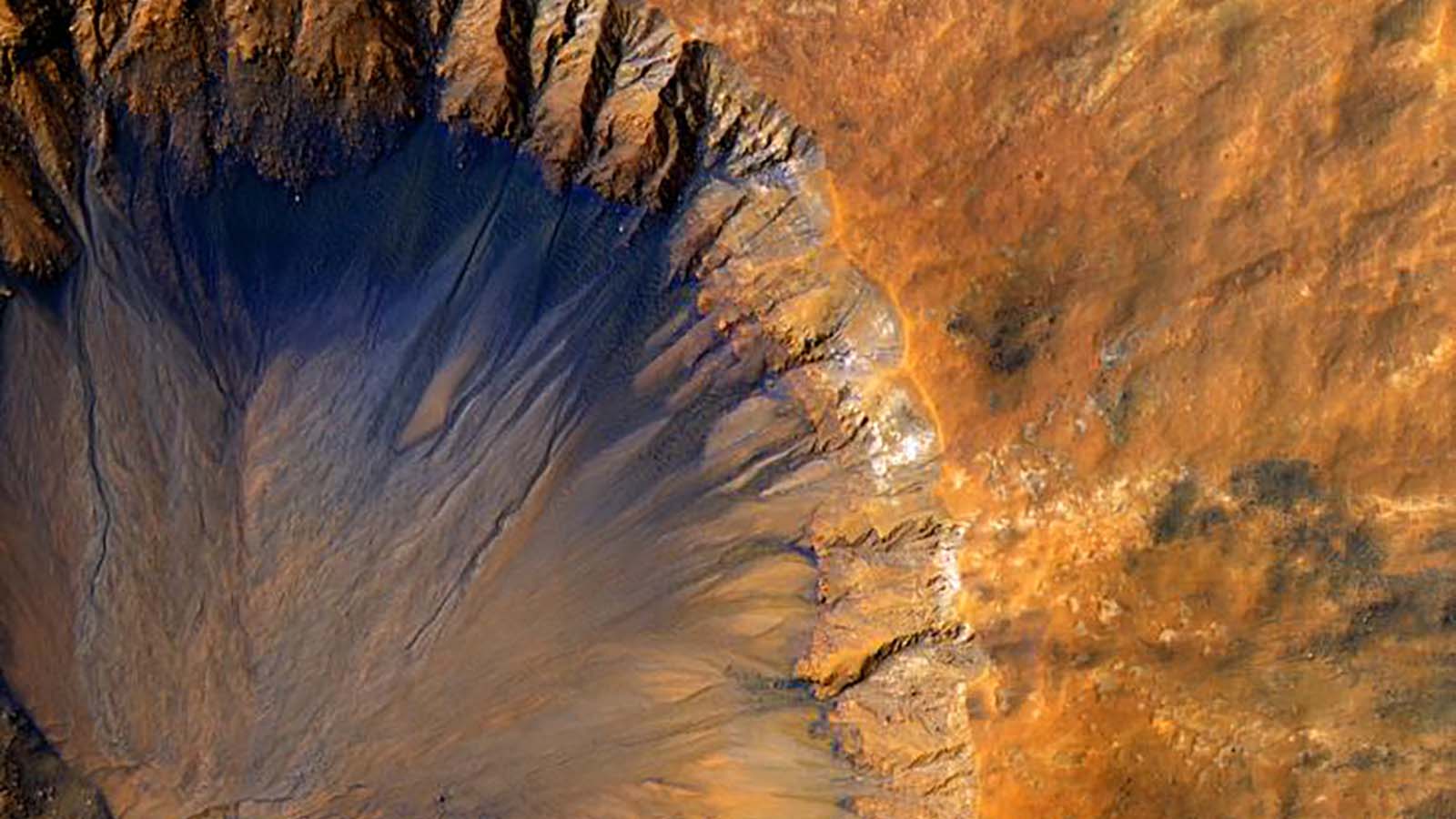

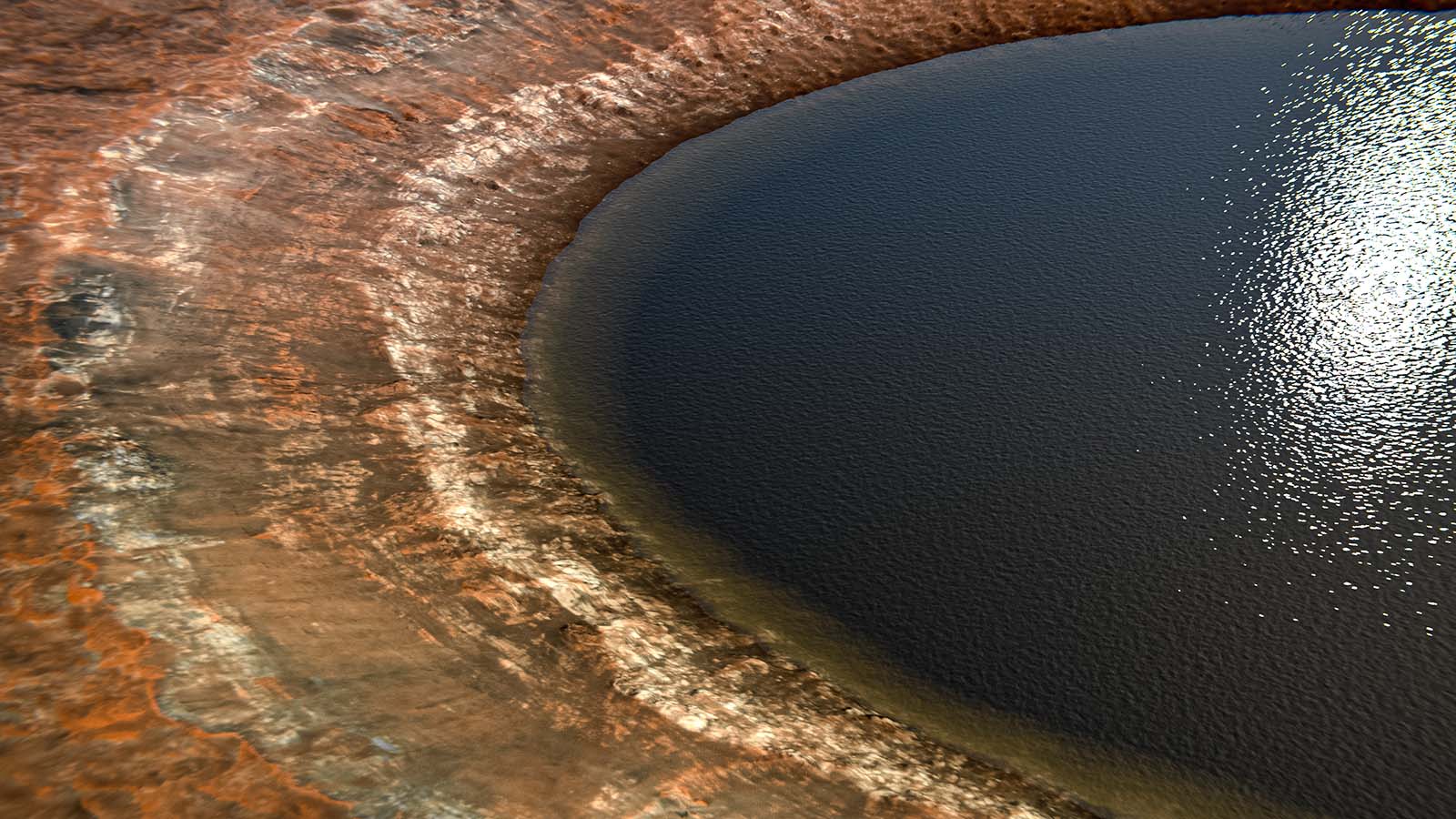

Planetary scientists studying Mars have long known that many of the various craters on the Martian surface were once filled with water about 3.5 billion to 3 billion years ago and that sometimes, just like here on Earth, those lakes would overflow the rim of the craters containing them.

These so-called lake breaches often lead to catastrophic flooding when they occur here on Earth, as the water breaking over the edge of the lake will quickly erode the sediment holding back the lake, tearing open an ever-widening breach for the massive volume of water in a crater lake to escape. Sometimes, it's enough for the water to just be near to overflowing the rim for the pressure to be too great for a crater wall to support and it simply ruptures, releasing the water contained within.

On Earth, geological processes have eroded most of the craters around the world so that very few remain, so most crater-like lakes here are actually the calderas of extinct volcanoes. Mars, on the other hand, is a very crater-filled place, and some of its craters are billions of years old.

Now, a new study published September 29 in the journal Nature from a research team at the University of Texas at Austin (UT) argues that these craters might hold the key to Mars' river-scarred landscape.

By examining more than 250 craters known to have suffered crater lake breaches in the past, the UT researchers found that the fast, extremely violent flooding from these lake breaches could have been what carved out many of the most dramatic river valleys and canyons on Mars' surface.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

"If we think about how sediment was being moved across the landscape on ancient Mars, lake breach floods were a really important process globally," Tim Goudge, assistant professor at UT's Jackson School of Geosciences, and the lead author on this week's paper, said in a statement. “And this is a bit of a surprising result because they’ve been thought of as one-off anomalies for so long.”

The lake breach events in the study were powerful enough to carve up and carry off enough Martian sediment to fill Lake Superior and Lake Ontario. We asked Goudge how much water might have been inside some of these crater lakes to get a better sense of the kinds of forces at work in this period.

"They greatly varied in terms of their volumes," Goudge told us, "but some were the size of small seas on Earth (e.g., Caspian Sea). These estimates come from past work by one of the co-authors, Caleb Fassett [in his 2008 paper]."

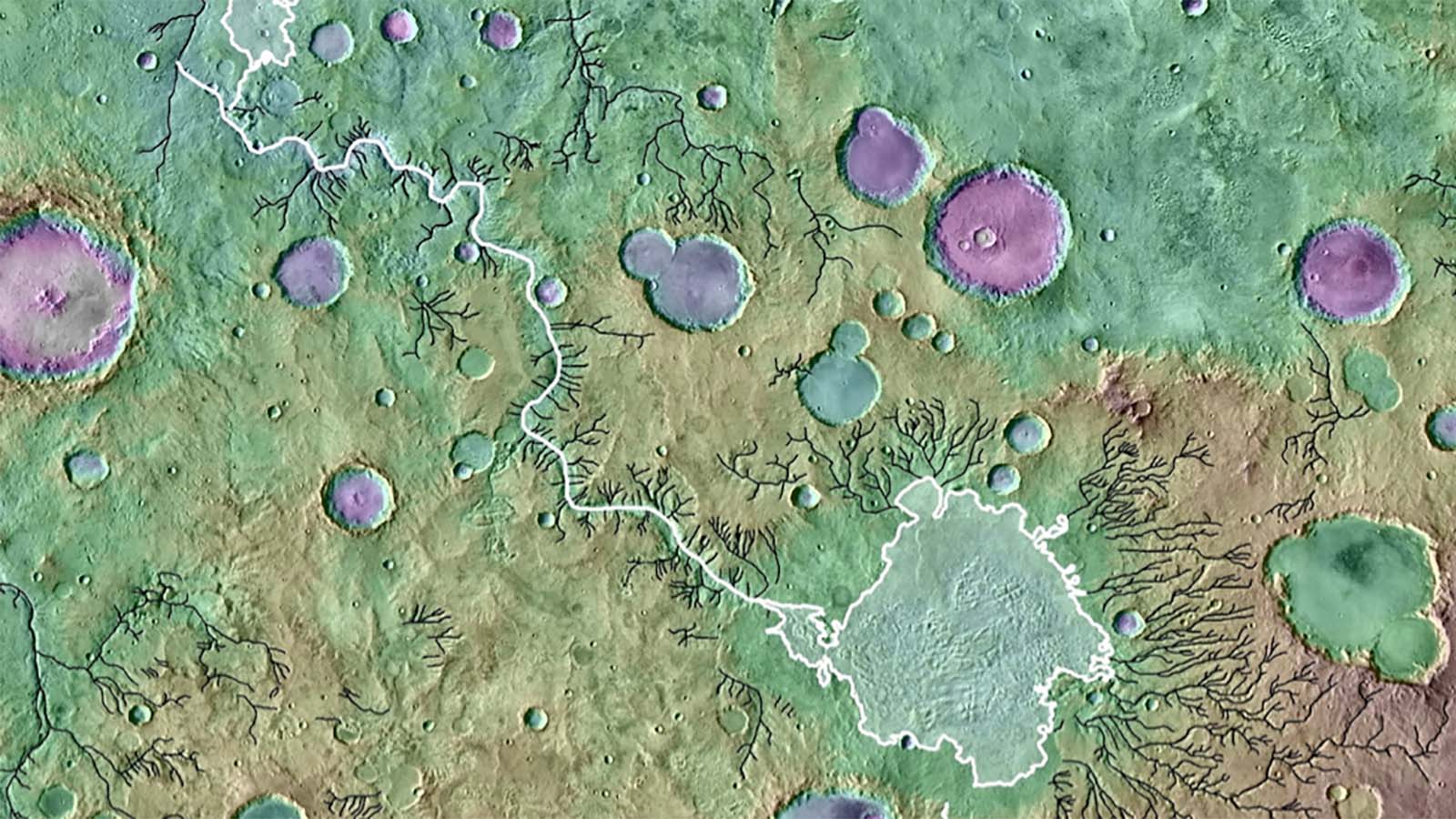

Using an existing catalog of Martian river valleys and identifying those that began at the edge of a crater, the UT researchers were able to isolate those that were the product of these lake breach floods and those that were produced by more typical and more gradual processes.

They found that even though lake breach flooding only accounted for 3% of total valley length on Mars, data from satellites in orbit around Mars showed that these events accounted for fully 25% of all eroded valley volume on the planet.

“This discrepancy is accounted for by the fact that outlet canyons are significantly deeper than other valleys,” said Alexander Morgan, research scientist at the Planetary Science Institute and co-author of the paper.

The resulting river valleys were also more than twice as deep, with a median depth of 559 feet (170.5 meters), as opposed to the more gradual valley's median depth of 254 feet (77.5 meters).

- Mars never had a chance: study says Red Planet just too small to hold onto water

- NASA Mars Perseverance captures teeny, tiny Martian moon Deimos on film

- Should we go to Venus instead of Mars?

What helps to account for this depth of carving is actually the height of the crater lakes in question, which were held behind crater walls that extended far higher than the local "seal level".

"Generally you have the local picture correct, although there is not quite a 'sea level' equivalent on Mars," Goudge told us. "There may have been oceans, but that is a very heavily debated question. But, the water levels within the craters were indeed much higher than the land outside the crater walls - essentially the crater acted as a dam holding back the water in its interior. When that dam failed, either by overtopping or some major land sliding or slumping, water began to rush out and rapidly carve the outlet canyon."

So where'd all that water go, we asked Goudge.

"Indeed a great question," he said, "and I think there was likely a mix of processes - some going to water ice – in fact, if you melted all the ice we know is present on Mars today, you could easily fill all the lakes in question! – some being lost to the atmosphere, and some being incorporated into minerals with water in their structure. For the latter idea, there is a really thought provoking article from Eva Scheller a few months ago in Science that I find super compelling. So I'd think those ideas play some role here."

Analysis: nature is awe-inspiring, even on other worlds

If this latest research is correct, it really does demonstrate the absolute raw power of nature. If human explorers wanted to carve out hundred-kilometer deep trenches in the Martian landscape, they would have to spend years or even decades blowing out dirt and material with explosives.

Explosives have given us the power to cut through mountains – eventually – but that pales in comparison to the power of even gently flowing water, much less the kind of powerful flooding events this new paper details that were carving out some of the largest canyons known in the solar system in just a few weeks or months.

“When you fill [the craters] with water, it’s a lot of stored energy there to be released,” Goudge said. “It makes sense that Mars might tip, in this case, toward being shaped by catastrophism more than the Earth.”

The Grand Canyon, meanwhile, took the Colorado river five to six million years to carve out.

Hopefully, by studying ancient flooding events like this in Mars' past, we'll be able to figure out where all that water went, and if its still there, somewhere, beneath the surface.

John (He/Him) is the Components Editor here at TechRadar and he is also a programmer, gamer, activist, and Brooklyn College alum currently living in Brooklyn, NY.

Named by the CTA as a CES 2020 Media Trailblazer for his science and technology reporting, John specializes in all areas of computer science, including industry news, hardware reviews, PC gaming, as well as general science writing and the social impact of the tech industry.

You can find him online on Bluesky @johnloeffler.bsky.social