Could Wi-Fi be replaced by Li-Fi?

Will Wi-Fi routers be outdone by a network of smart light bulbs?

By 2020, Wi-Fi will connect 1.7 billion devices, according to Cisco. However, by 2025 the growth of wireless data traffic could mean that the radio frequency (RF) spectrum Wi-Fi occupies will not be able to cope with demand. Cue Li-Fi, which uses part of the visible light portion of the electromagnetic spectrum to transmit information at very high speeds. Could Li-Fi takeover from Wi-Fi?

How does it work?

While a Wi-Fi network makes use of radio waves to transmit information across a network, light fidelity – aka Li-Fi – transfers data through light waves. "The concept of Li-Fi came about after an Estonian company called Velmenni conducted a real-world test in which it was able to transfer data at 1Gbps, which is approximately 100 times faster than Wi-Fi," says Albie Attias, managing director of IT hardware reseller King of Servers.

"Similar to the infrared technology found in TVs, Li-Fi works by turning an input command into binary code, which is then transmitted through infrared light waves by the remote's sensor," adds Attias. "The light waves are then decoded and perform the intended action."

Li-Fi tech could be used in cars, planes, solar panels, around schools and lecture theatres, during disasters, on oil rigs and in nuclear power stations, around hospitals, or in homes and workplaces.

What is VLC?

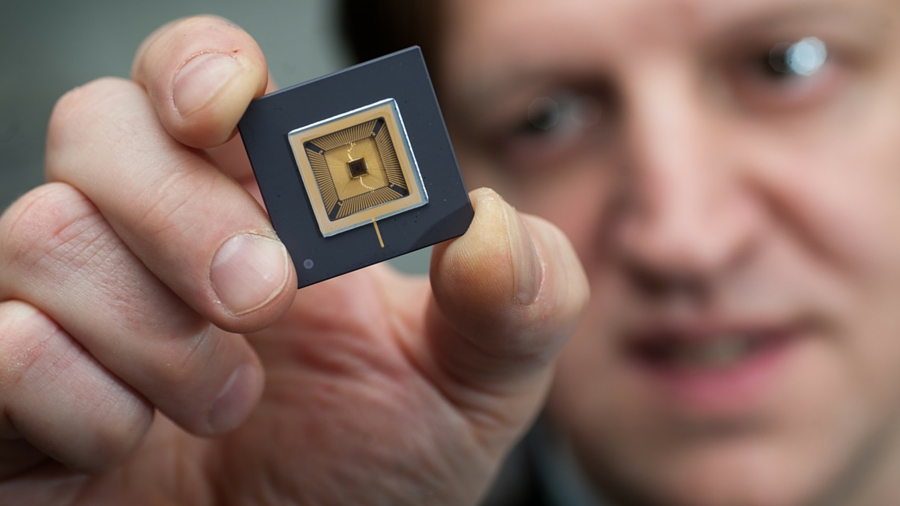

The technology behind Li-Fi is called Visible Light Communication (VLC), and it's akin to Morse code. "It works by controlling the number of photons emitted by LEDs and doing this in a manner that is not detectable by humans even though it uses the visible light spectrum," says Andrew Ferguson, editor of thinkbroadband.com. "Li-Fi is the named adopted for the transmission of data using visible light and thus reflects the shift from the radio frequencies of Wi-Fi – i.e. 2.4GHz and 5GHz – to the visible light spectrum of 430 to 770THz." This carries the potential for very high transmission rates.

Here's one scenario that could make Li-Fi genuinely useful: you want to sync your laptop with a cloud server to download a lot of data – or you want to download a 4K movie to your tablet – so you hold the device in sight of the Li-Fi-enabled light bulb in your living room… for just a couple of seconds.

VLC is being explored by Disney Research, while Qualcomm has its Lumicast technology, which could be employed in LED lighting fixtures where Li-Fi is used to transmit indoor location data.

Are you a pro? Subscribe to our newsletter

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

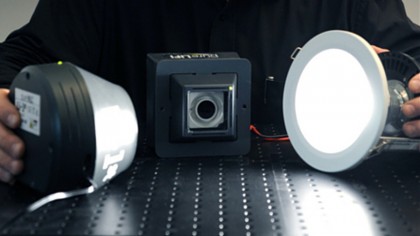

What would a Li-Fi network look like?

Light bulbs. That's it. Rapid changes in light levels – not visible to the eye – are what transmits the data. "The latest innovation is totally wireless, and can operate with existing LED bulb technology," says Attias, who states that to go mobile, Li-Fi would require smartphones and laptops to be fitted with a photosensor to read incoming light. It could happen to the iPhone. While the Li-Fi industry waits for phone-photosensors, a company called Zero. 1 is using the front and rear cameras on smartphones in a Dubai-based Li-Fi test project at Dubai Silicon Oasis.

Who is promoting Li-Fi?

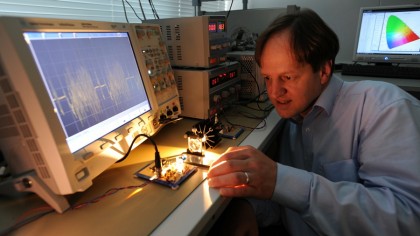

Li-Fi's biggest advocate is Harold Haas, a professor at the University of Edinburgh who gave a TED talk on Li-Fi, which included a demo, in 2011, then founded pureLi-Fi. The first Li-Fi-enabled light bulb, created by pureLi-Fi and LED maker Lucibel, is expected towards the end of 2016.

Dozens of other companies are involved in Li-Fi research, including Lucibel, Oledcomm, LG, Philips, Samsung, Toshiba, Sharp, Panasonic, Cisco and Rolls Royce, while there are various independent Li-Fi projects, too.

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),