Our remote-first future has turned HS2 into a glaring anachronism

Covid-19 poses an existential threat to the traditional commute - and perhaps to HS2 as well

The UK’s High Speed 2 (HS2) rail project has been a bone of contention ever since it was first proposed in 2009.

The new rail line - which is set to run 345 miles between London, Birmingham, Manchester and Leeds - was billed as a means of better connecting the North and South and “levelling up” Britain’s transport infrastructure.

However, doubts over the scheme’s environmental credentials, repeated delays and ever-inflating cost projections have long cast a shadow over the endeavour.

- Here's our list of the best collaboration tools out there

- Check out our list of the best office chairs available

- We've built a list of the best productivity software around

The most ardent critics have branded HS2 a “vanity project”, accusing the UK government, which has decided to proceed with the scheme after a recent review, of falling victim to the fallacy of sunk costs.

And today, in the context of the coronavirus pandemic and rise of remote working, critics of the embattled HS2 initiative may yet have another (even larger) stick with which to deliver a beating.

Demand for travel in a remote working world

Although the project has been branded High Speed 2, a more accurate name would perhaps have been High Capacity 2; the rail’s true raison d'être is (or perhaps was) to alleviate congestion on UK rail routes caused by ballooning passenger numbers.

The shared experience of commuting professionals, crammed into trains that are both too small and rather worse for wear (a privilege for which they were paying a fortune), gave HS2’s proponents a clear objective to hold aloft.

Are you a pro? Subscribe to our newsletter

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

However, the meteoric rise of remote working - made necessary by the pandemic and subsequent lockdown - may yet challenge the assumption that the commute is here to stay.

During lockdown, when all non-essential travel was outlawed, traffic on public transport predictably fell through the floor. In the lockdown period, National Rail footfall fell to between 4-6% of usual levels, while Transport for London reported a similar drop in the capital.

But what is most notable is the enduring unwillingness to return to the railway. National Rail traffic remains at below 40% of usual levels and roughly the same can be said for the London Underground.

According to another recent Government survey, 89% of the population would be concerned for their health if they had to travel via train at the present moment, and 88% feel the same about trams.

Over a third are walking or cycling more than before the pandemic, instead of taking public transport, and 94% of this group claim they will continue to do so once restrictions are fully lifted.

The pandemic may also fuel a mass exodus from larger cities, as residents no longer tied down by their jobs seek more spacious environments and cheaper accommodation - and even the chance to get on the housing ladder.

The latest data suggests 14% of Londoners wish to leave the city as a result of the pandemic, which equates to more than a million people. Along with financial motivations, the location of work (or rather lack of location) was cited among the top reasons for moving out of the city.

While this data relates to the capital specifically, it doesn’t take a drastic leap in logic to assume residents of HS2 hubs Birmingham and Manchester might be feeling the same way.

The Government claims that HS2 is “already providing the platform for Birmingham to boom, with more new jobs, more new businesses being set up and more outside investment.” But might businesses think twice about a flash new Midlands headquarters if employees, many of whom no longer live in the city, can function equally well over Zoom?

While attitudes to both travel and living will likely change as society comes to terms with a post-coronavirus future (vaccine or no), what’s certain is that the traditional nine-to-five and full-time office work are dead in the water.

In a world in which commuting hours are no longer as busy as they once were and fewer people are travelling to the office every single day of the week, for how long can the Government continue to justify the projected £106bn expense on HS2?

For context, Westminster has so far committed a comparatively miserly £6 billion to rolling out Gigabit broadband - a project that would assist the UK workforce in a much more direct manner in current circumstances.

Alternatively, with a spare hypothetical £100 billion, the Government could purchase 10 million 4G routers and 10-year broadband subscriptions to go with them - and still have money leftover.

The case for continued work on HS2

According to a spokesperson from the Department for Transport (DfT), the Government remains as committed as ever to HS2, with a reduction in carbon emissions and a boost to jobs cited as key benefits.

“Our absolute priority right now is on tackling Covid-19 and rebuilding our economy. HS2 will provide thousands of jobs and skills opportunities and the start of construction is a vital part of our economic recovery,” the DfT told TechRadar Pro.

“The project is also key to boosting connectivity and opportunities across our towns and cities while supporting the Government’s goal of reaching carbon net-zero by 2050.”

However, the department did not rule out alterations to the project (or even outright cancellation) in light of the coronavirus situation, which may well play havoc with the sums and reasoning used to justify its existence.

“As part of our twice-yearly reports to Parliament on the status of the project, we will consider the longer term impacts of Covid-19 once the pandemic’s wider effect on the economy becomes clearer,” explained the department.

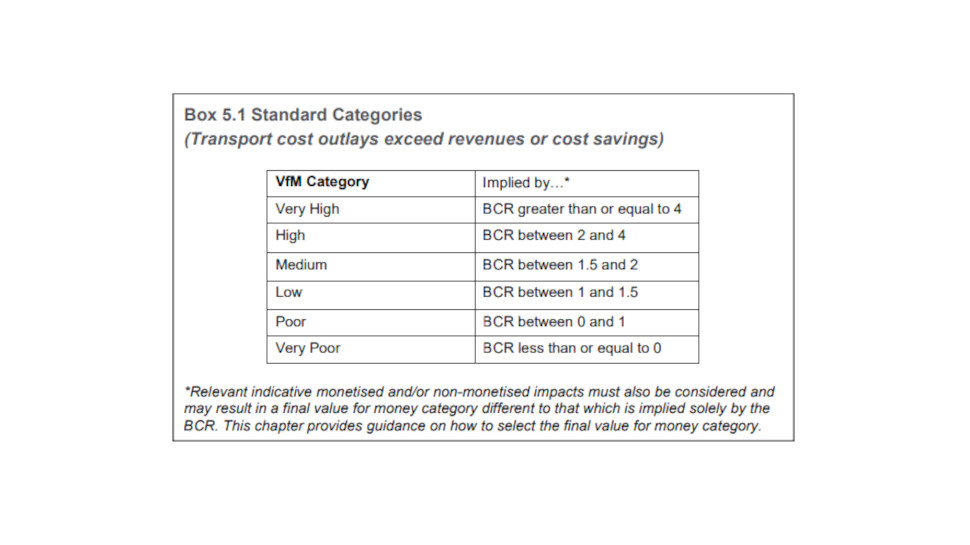

If it were to emerge, when the sums are next recalibrated, that for every pound spent on HS2 less than one pound will be returned in value, the Government will have to front up serious questions about the misuse of taxpayers’ money.

As per the department’s own framework, “achieving value for money can be described as using public resources in a way that creates and maximises public value.”

“Public value is defined as the total well-being of the UK public as a whole. In a transport context, this covers all the economic, social and environmental impacts of a proposal.”

This equation could be made all the more difficult to balance by question marks over whether remote working has made HS2 redundant before its first train has even had the chance to fire its engine.

Determining value for money

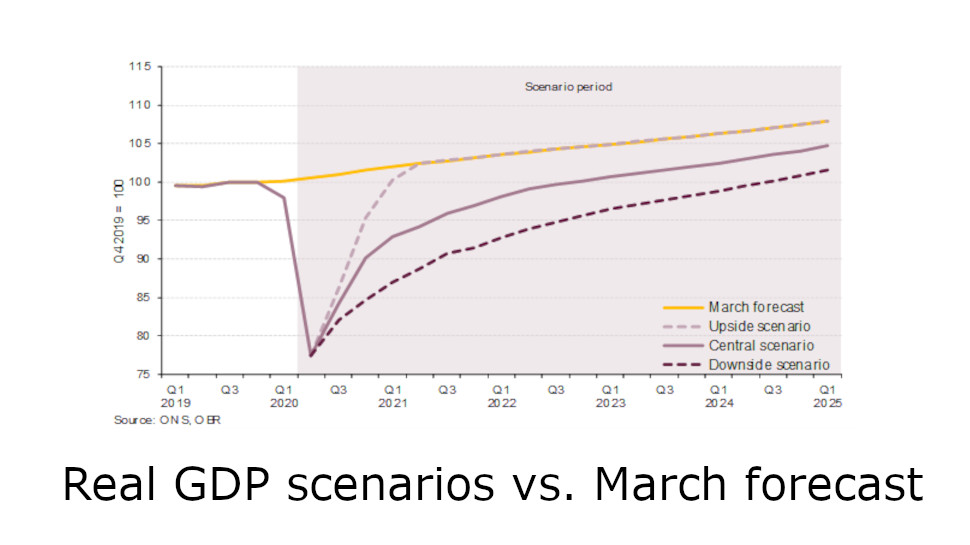

The latest medium-term forecast from the Office for Budgetary Responsibility (OBR) was published back on March 11 but, due to the period of economic turbulence that followed, has been made largely irrelevant.

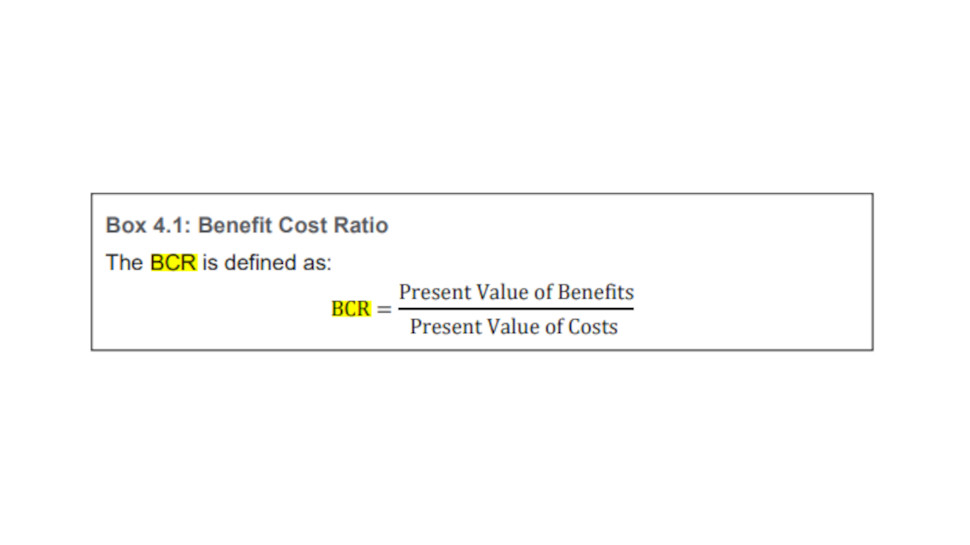

Traditionally, this forecast sets out a five-year outlook for the UK economy, which then can be used as a jumping off point for estimating the benefit-cost ratio (BCR) of Government projects, such as HS2.

The next full medium-term forecast won’t arrive until mid-to-late November, but the OBR has published supplementary material in the interim, designed to address the economic uncertainty brought about by the pandemic.

According to a fiscal sustainability report published in July and a monthly commentary report from September, the deficit has more than trebled since April (reaching £174 billion) and the UK is set to record the largest decline in annual GDP for 300 years. Central government spending is also up 33%, HMRC cash receipts are down 26% and net debt is at its highest level since 1960-61.

What does this mean in the context of transport? Well, less prosperous economic conditions mean fewer people are likely to travel for leisure, businesses will seek out cost-cutting measures (which could include minimizing travel and closing physical offices) and a rise in unemployment will mean fewer commuters too.

Both reports are also careful to note that high levels of uncertainty make assessing fiscal sustainability extremely challenging and the full extent of the damage will therefore remain unclear for some time yet.

“The coronavirus outbreak and the public health measures taken to contain it have delivered one of the largest ever shocks to the UK economy and public finances,” explained the OBR.

“Today’s data highlight the growing fiscal cost of the coronavirus crisis, although it will still be many months before the full impact of the shock becomes clear.”

All of this suggests that November’s mid-term forecast, when it does land, is likely to paint a rather bleak picture - one that is far more troubling than the forecasts last used to conduct an appraisal of HS2 costs and benefits.

Is it only a matter of time?

The Full Business Case (FBC) for HS2 Phase One (the leg from London to Birmingham) was published back in April, at the height of the initial wave of coronavirus in the UK.

The document, which is designed to justify the continued work on HS2, communicates a firm belief in the merits of the project, but also demonstrates an acute awareness that a return on investment is not a certainty.

Prior to the pandemic, HS2 Phase One was already adjudged to deliver “low” value for money, meaning the benefit-cost score would fall between 1 and 1.5. But with the completion of the Y-shaped extension, connecting Birmingham with Manchester and Leeds, the project as a whole was expected to represent “medium” value for money, with a healthier BCR score of between 1.5 and 2.

However, as revealed by the FBC, which factors in low travel demand scenarios brought about by the pandemic, the previous assessment of the project’s value may prove invalid.

In a high demand scenario, Phase One is still expected to have a BCR score of 1.2, but if demand is even as much as 16% lower than was predicted pre-Covid, the project plummets into the “poor” value for money category with a measly BCR of 0.3.

The report is careful to emphasize that the pandemic has ruled out certain types of analysis, making a categorical value for money assessment impossible.

However, the picture today is likely a whole lot clearer (if not yet crystal) than it was in April when the report was compiled. And, when the OBR forecast lands next month, it’s possible the status of the HS2 project will shift from merely controversial to outright scandalous.

The greatest irony is that the press conference announcing the scheme’s cancellation, if and when it occurs, will likely be delivered via video conference - the very medium that helped seal its fate.

- Here's our list of the best project management software around

Joel Khalili is the News and Features Editor at TechRadar Pro, covering cybersecurity, data privacy, cloud, AI, blockchain, internet infrastructure, 5G, data storage and computing. He's responsible for curating our news content, as well as commissioning and producing features on the technologies that are transforming the way the world does business.