Beyond GPS: The future of location tech will change how you use your smartphone

Creepy? Yes. Useful? Absolutely

Having your phone know where you are and what you're doing is one of the creepiest (but most useful) aspects of modern smartphones. From Google Now to location-based notifications on iOS, you probably take advantage of it every single day.

But we're still using 1970s technology to make that happen, and when the tech finally catches up with the 21st century, it'll change how you use your phone, for the better. Mostly.

At the moment, your phone uses two main methods to work out where you are – the Global Positioning System (GPS) and Wi-Fi. GPS, as you're probably aware, is a system that uses a global network of satellites to work out where you are.

The status quo

There's a constellation of 24 American military satellites (up until 2000, the rest of us couldn't really use it) that are spread out around the entire world. When your phone wants to know where it precisely is, it tries to acquire the signal beamed out by at least four of the satellites. It then decodes that using some fancy maths invented by Einstein, and can thereby work out where it is in the world, down to an accuracy of around 5 meters.

It's an incredibly clever system, and absolutely perfect for applications like sat-nav. But for smartphones, GPS actually kinda sucks. It's hugely battery-intensive to have on all the time, clouds or slightly-too-high buildings can foil it, and it doesn't work indoors.

To try and get around this problem your phone uses an alternative system: Wi-Fi location. Thanks to a couple of vast databases that cross-reference Wi-Fi network data with geographical location, your smartphone can normally work out where you are in the world in under a second. It does so by looking at what Wi-Fi networks you can see, and cross-referencing the network names with where they are on a map.

The data for these databases is collected either through "wardriving" (cars with Wi-Fi antennas driving around, collecting the data) or, more commonly, by using every smartphone on a given platform. So, when you have GPS and Wi-Fi switched on, it's quite possibly gathering data about nearby Wi-Fi hotspots and phoning it home.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

It's far less accurate, but because it's using a fairly low-power sensor (the phone's Wi-Fi chip) rather than trying to communicate with satellites in outer space, it's a good option when you only need to know roughly where you are.

Of course, there's one other, even less accurate location-finding method that your phone can use: cellular triangulation, which is the thing referenced in early episodes of 24, with Jack Bauer hunched over a laptop trying to track the baddies.

Cellular triangulation can work out where you are to within a couple hundred metres (or, sometimes, a couple hundred kilometres) by looking at which cell towers your phone is communicating with, and basically putting you in the rough nearby area. It's not a particularly useful tool (unless you're Jack Bauer), but it is somewhat handy for determining initial location, before GPS gets on with the job.

The space race

The most immediate and subtle change to location technology that you'll probably see is the switch away from GPS, towards other satellite-based systems. GLONASS (Global Navigation Satellite System) is the Russian version of GPS, and it too uses 24 satellites to give global coverage.

It doesn't really offer any advantages over GPS in and of itself, but having access to two systems doubles your chances of getting a signal quickly.

Which explains why Apple's included a GLONASS chip in every iPhone since the 4S, and most Android manufacturers have followed suit. (Well, that, and the fact that Russia has a 25% import tax on any non-GLONASS-enabled handsets these days, so most manufacturers find it worthwhile to stick the extra chip in.)

Europe's challenge to GPS dominance is a system named Galileo. It works on exactly the same principle as GPS and GLONASS, a bunch of satellites orbiting Earth, but offers a few advantages. It has much better accuracy with altitude, and a function that'll turn your phone into a rescue beacon that can summon Mountain Rescue or the Coast Guard with the push of a button, even if you're out of mobile phone reception. Unfortunately, since Galileo is an EU project, it's running quite a long way behind schedule and over budget, and isn't quite reality yet.

It's not all about the astronauts

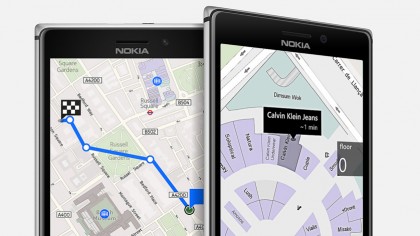

But even with this new host of satellite systems on the market, your phone still can't accurately work out where you are indoors. That's a problem, because indoor location services would open up a whole host of possibilities. When you're out shopping, you'd be able to navigate round a giant supermarket to find things or the Tescos app could give you a route, based on your shopping list, to get in and out as fast as possible.

Or, when you're at home, smart thermostats and lighting systems could use your phone's location to work out where you are in the house, adjusting lighting and temperature accordingly. The possibilities are huge, and just like with most new tech, it's impossible to predict what developers will do with it. After all, no-one would've predicted that opening the iPhone up to apps would lead, seven years later, to the existence of Flappy Bird.

A magnet and a seismometer walk into a bar…

Thankfully, a bunch of clever start-ups and established R&D labs are already working on making indoor location technology work better, with a whole laundry-list of different approaches.

One of the more mature technologies for indoor location tracking is our good old friend, Wi-Fi. With the installation of antennas around a shop (or anywhere else, for that matter), a far more accurate Wi-Fi grid can be built up, which allows phones to be tracked to an accuracy of around a metre. That's good enough for most purposes, like finding items on shelves.

It's also good enough for shops to be able to track customers in store, which is what the technology is currently (and very quietly) used for. A whole host of firms offer "in-store analytics" for retail chains, which basically amounts to tracking unsuspecting customers' phones using Wi-Fi, looking at the path they take around the store and what products they pause over, and then feeds that information to the stores.

However, far less sinister technologies also exist, and also require far less hardware than Wi-Fi solutions, which require dozens of antennas for just one building. IndoorAtlas is a US-based company that maps buildings based on their 'magnetic fingerprint'.

Basically, they use the fact that minor variations in steel structures give buildings a unique magnetic field, which can be used to geo-locate a phone with accuracy of a metre or two, without needing to install any new transmitters.

Even better, most phones already have magnetometers already installed, and they use very little battery power. Once the initial mapping of a building has been done, there's little to stop magnetic location becoming the new standard (unless we all choose to live in mud huts, of course).

Another slightly quirky location concept is the Open Positioning System, which wants to use existing low-frequency sources of seismic noise, things like power station turbines, for example, to triangulate location, without needing an expensive satellite system and without being hindered in the slightest by cities. The idea, developed by a Royal College of Arts student, is still in beta testing at the moment.

With so many different options, however, the most promising solution of all could be some kind of hybrid. BAE Systems, a British engineering firm, has a research project that uses a whole mix of electromagnetic signals from TV broadcasts, to Wi-Fi and cell towers to work out your location. The theory is that whie one single system might not offer universal coverage or great accuracy, bundling them all together probably will.

AlterGeo is a company that already uses this approach for positioning: it uses Wi-Fi, WiMAX, GSM, LTE, IP addresses and network environment based location algorithms to serve location requests. It's not hard to imagine adding in magnetic and seismic data, in addition to the hundreds of location satellites already floating overhead, to work out exactly where you are, indoors or outdoors, with zero effort.

While that might have privacy advocates running for the tinfoil and blackout blinds, being able to work out your location should vastly improve our smartphones in the future. The current generation of smartphones, like the iPhone 5S and Moto X, put "contextual computing" at the forefront of your handset.

They pride themselves on being able to offer relevant information, whether that's the current weather, train times or football scores, and better location information will drastically improve how well they can do that. The end result? Prepare to be even more attached to your smartphone – but don't worry if you lose the damn thing, you'll know exactly where to find it.

- Here's how to use a VPN to change location