Project Ara: your next smartphone is one you'll build yourself

Google's blueprint for the first modular phone is here and it's impressive

Back in October 2013, a YouTube video called Phonebloks took the tech-loving corner of the internet by storm. It showcased a concept for an entirely modular smartphone, where individual components could be changed out on a whim (or as they became obsolete).

In just a few months, one of Google's elite R&D teams (which was borne out of the acquisition from Motorola), spearheaded by the ex-manager of the secretive US DARPA research team, has taken Phonebloks a big way towards reality: designing an in-depth vision for how the modular phone (now codenamed Project Ara) will fit together and run.

The culmination of their effort is an 80-page document for third-party manufactures who want to build modules for Ara; outlined inside is a comprehensive vision of how Google sees the future of smartphones - and the good news is that even with the sale of Motorola to Lenovo, the modular phone creation is staying firmly locked in Google's mysterious project cave

Hardware

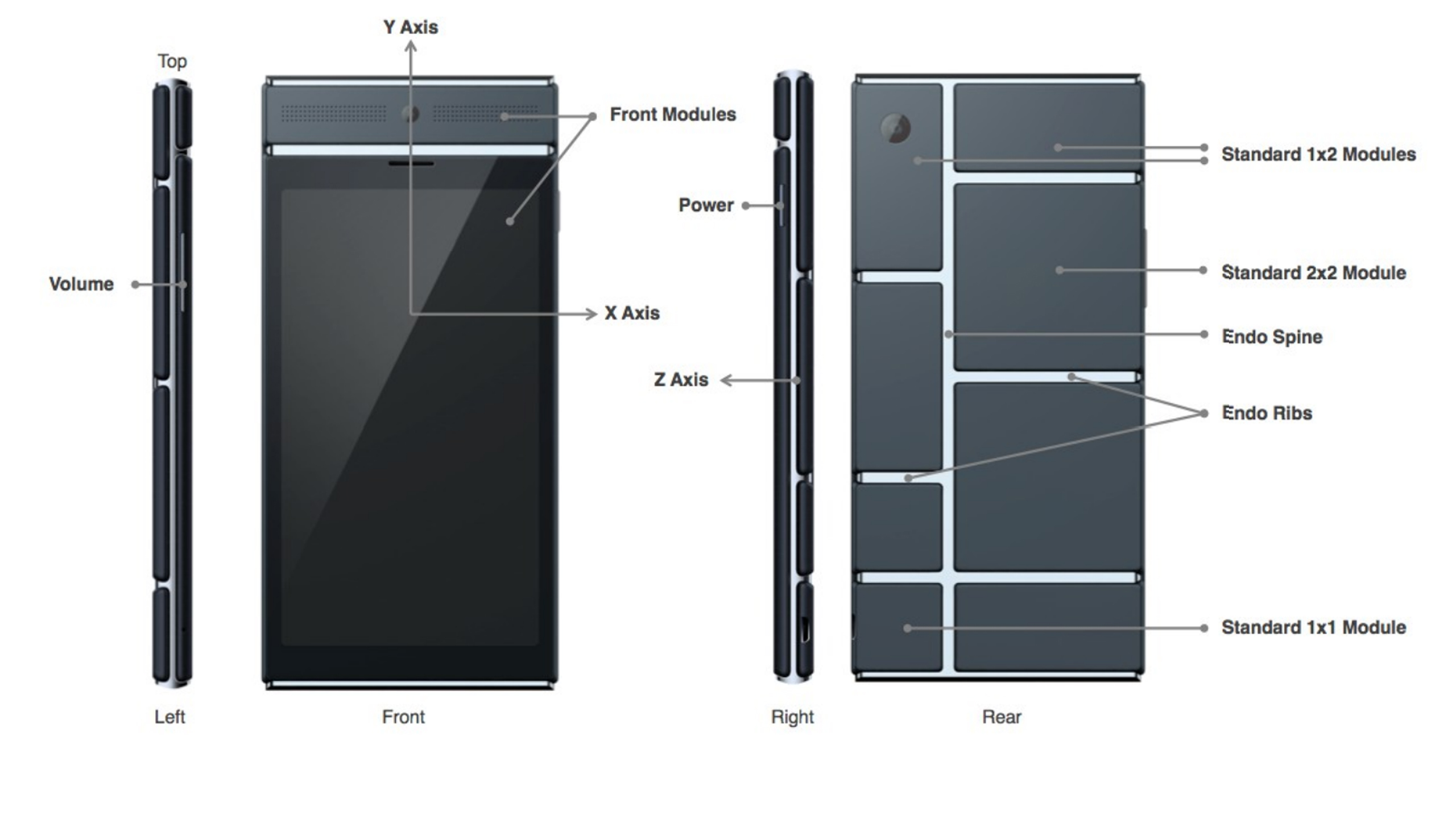

An Ara phone starts life as an endoskeleton (or 'endo', to its friends). Basically a bare motherboard with no screen, processor, battery, or anything you'd normally associate with a smartphone.

Then modules, bought separately or as part of a kit, can be attached to the endo to create a complete phone, which you can switch around at the push of a button to fulfil your particular needs – or that's the idea, anyway.

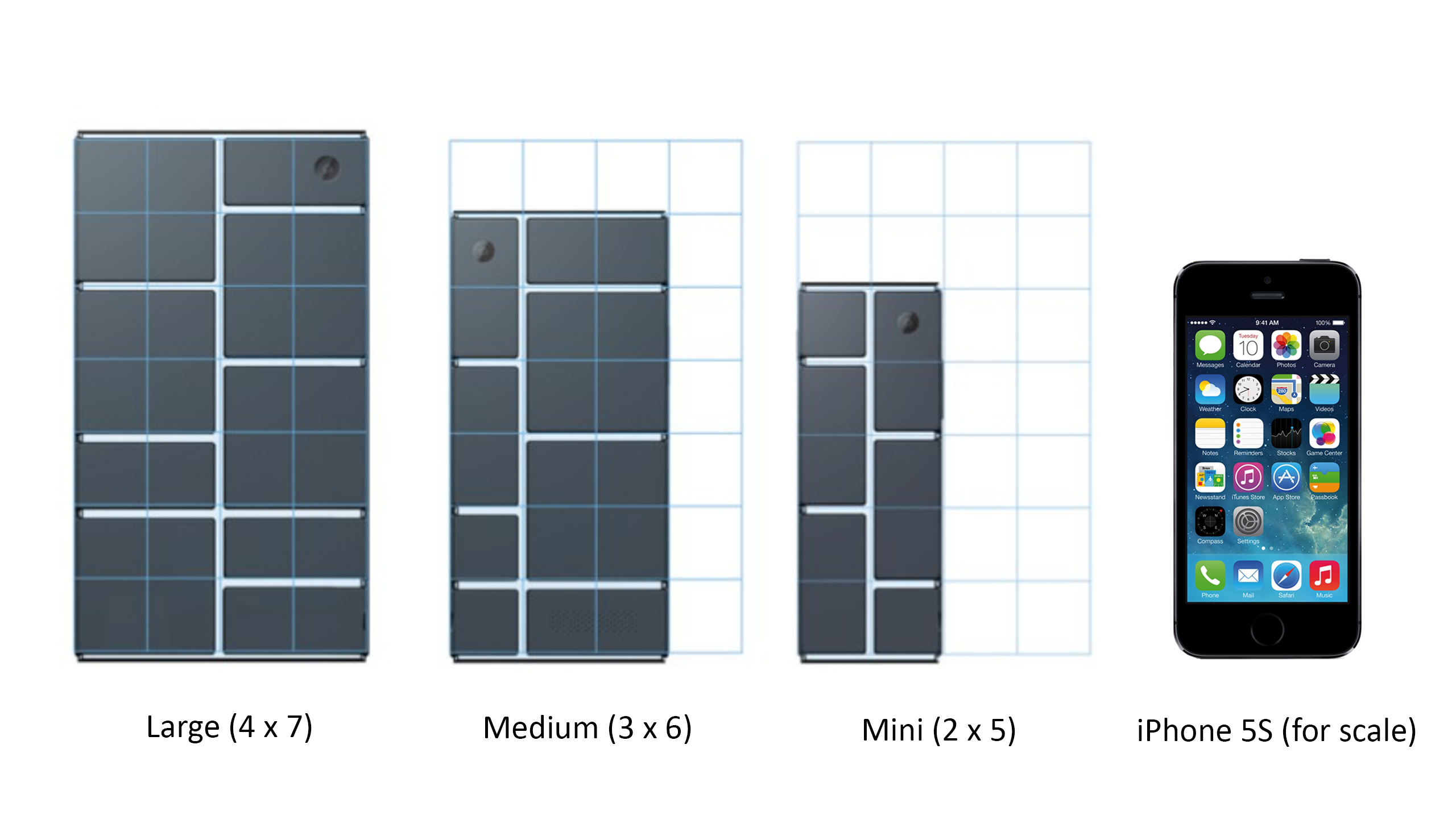

Initially, Google's planning on manufacturing two endos: a thin 'Mini' and a 'Medium', which is almost exactly the same size as a modern Samsung Galaxy S5. There's also the possibility of a phablet-busting 'Large' version coming out further down the line.

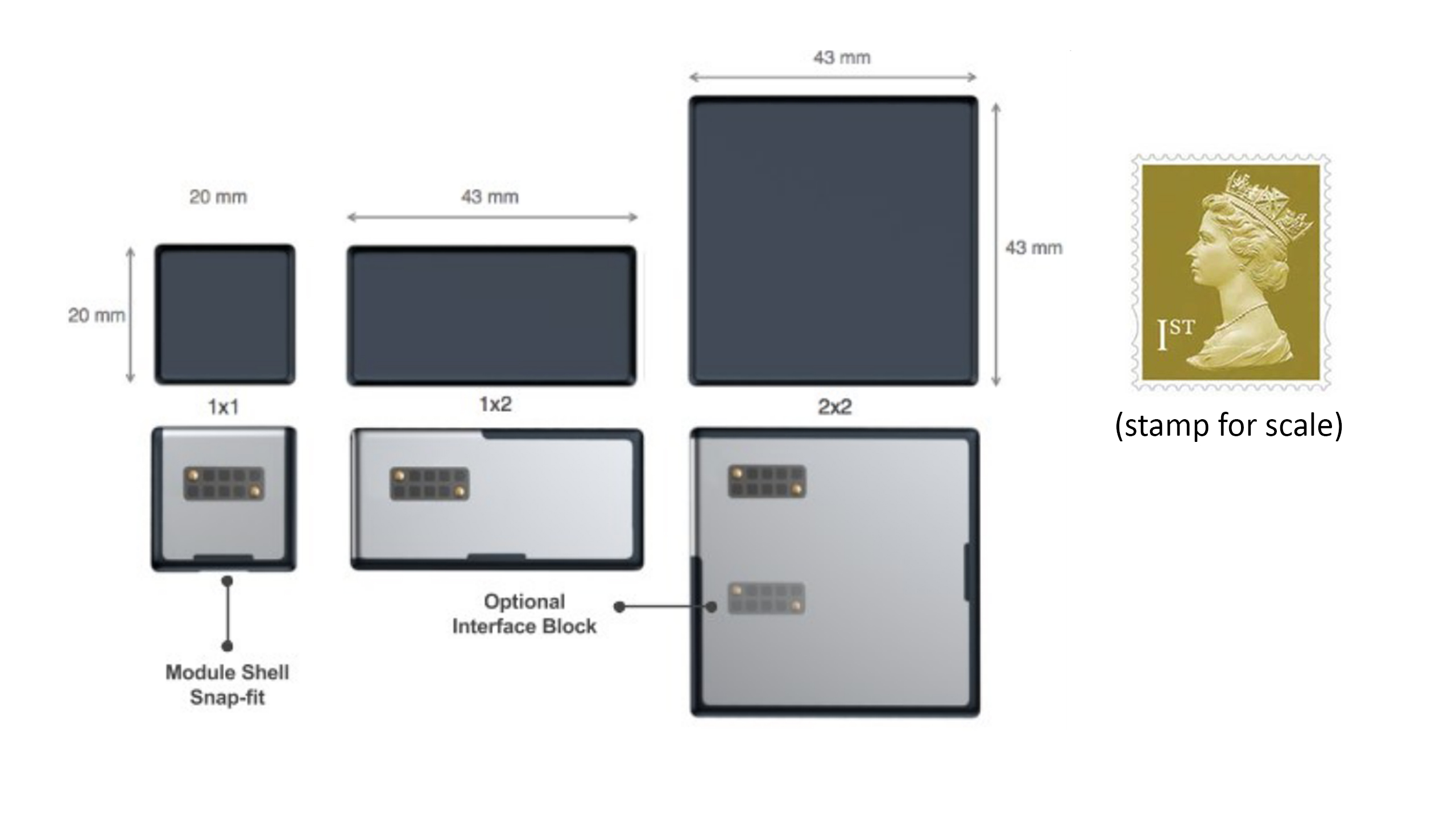

It's all based on a grid, where each square is approximately 22mm x 22mm.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Each endo has a front and a rear: the front is basically just one big slot for the screen, perhaps with a bar along the top for a front-camera/speaker module.

The back is where most of the modules live. It's divided down the middle by a spine; the spine then has ribs that shoot off to the side, ultimately dividing the back up into slots of size 1x1, 1x2 or 2x2.

The modules lock into these slots by way of electro-permanent magnets (EPMs). These are a hybrid of electromagnets and normal permanent magnets, which can essentially be turned on and off by having a current passed through them.

Once the magnet is turned on it stays in that state without needing to have electricity flowing through it, unlike a conventional electromagnet. The connection should be pretty robust – Google says that all Ara phones must be able to withstand a 4-foot drop and fairly intense vibration test.

Click here for the full res version of this image

The electro-permanent magnets will be controlled through an EPM application, where the user will be able to see what modules are attached, whether they're locked in or not. You'll also be able to activate/deactivate the magnets on a per-module basis, using the touchscreen.

The modules themselves can be 1x1, 1x2 or 2x2, although 1x1 modules are apparently non-functional on the current prototype. Every module communicates with the endo via an 'interface block', a little connector that provides power and data flow to and from the module. A battery module could provide power via the interface block, and a processor module would draw power and so on.

This interface will probably prove to be one of Project Ara's limiting factors: the goal of Ara is that as processors and RAM increase in power, users can just keep upgrading those specific modules to keep their phones at the cutting edge. For that to work, however, an interface that lets all the modules talk to each other has to be able to keep up.