Why your smartphone PIN isn't as safe as you think

There's always someone out to get you

We all know the dangers. The smartphone is the portal to online shopping, our bank accounts and all manner of social network profiling. For many, it is our digital identity.

We know what we have to do: make sure it has a lock code and never share it with anyone.

But what if even that isn't enough?

Researchers at Cambridge University discovered a way to extract the PIN on an Android phone by using a malicious app to capture data through the smartphone's camera and microphone. This technique made headlines towards the end of 2013, as it was able to correctly identify a four-digit PIN from a test set 30% of the time after two attempts, rising to 50% after five attempts.

Flanking manoeuvre

This technique is known as a "side-channel" attack and it's noteworthy because it circumvents the supposedly secure split between the Android system and the trusted zone on your smartphone.

Side-channel attacks use sensors such as the gyroscope and accelerometer, or hardware such as the microphone and camera, in order to capture data. This is then uploaded to a remote server where an algorithm is used to take an educated guess at your PIN.

The "trusted" part of your phone is separate from the main OS and is designed to isolate sensitive applications, such as banking apps. This is all part of a move to keep sensitive data on separate hardware, with companies like ARM inventing the technology TrustZone, and GlobalPlatform (GP) creating standards for a Trusted Execution Environment (TEE) to ensure this stays secure.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

However, this approach doesn't protect against side-channel attacks. Laurent Simon, one of the authors of PIN Skimmer: Inferring PINs Through The Camera and Microphone, told us: "It's not obvious that the accelerometer or the microphone could be used to leak information. The focus is on securing the screen."

How does it work?

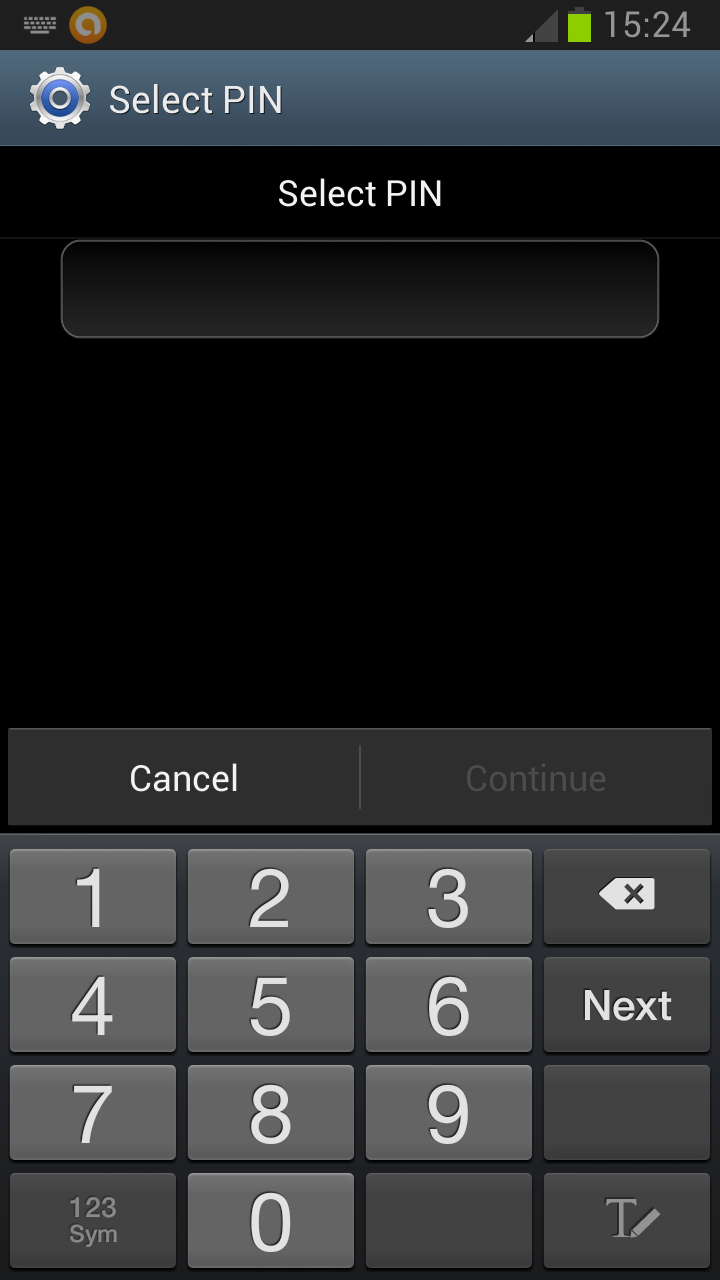

This attack involves using the PIN Skimmer app, which is malware disguised as a game, to record users interacting with the touchscreen.

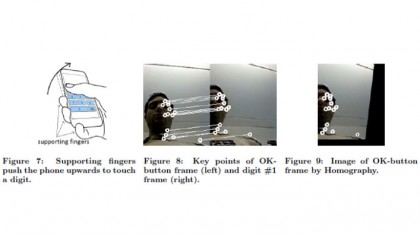

The front-facing camera can be used to capture a shot of the user and determine what they look like when pressing a specific point on screen. This data can then be used to build a model and analyse a video of them entering their PIN.

This is further bolstered by using the microphone to capture audio of the haptic vibration feedback when the user presses the screen in specific spots.

In fairness to phone developers, victims have to download the app and grant it permission to access the microphone, the camera, and the Internet in the Android system.

Once the attacker identifies a likely PIN, they still need the smartphone physically in hand before they can try it. As Simon explained, "In that sense it's limited, you can't do everything remotely; you would need to [inadvertently] collaborate with thieves."

Before you dismiss this idea as never going to happen to you, consider that malware can also be used to track your location and that smartphone theft is at an all-time high. The Met revealed that there were almost 100,000 mobile phones stolen in London alone during 2013.

How can you protect yourself?

Marc Rogers, Principal Security Researcher at mobile security specialist Lookout, told us: "The absolute, most common method of compromising your smartphone is installing something from a third-party store that will send out your phone number, your contacts list, your SMS messages, and allow someone to remotely control the phone.

"We did a study and we found in the US and UK that the likelihood of encountering something nasty - a phishing link, adware or malware - is around 2% to 3%. Your probability of actually encountering malware is about 0.5%."

Those figures are based on data captured from millions of Lookout Mobile users, with Rogers suggesting that users should stick to Google's Play Store and not go to third-party stores. "These don't necessarily have the same level of protection," he said, "and that's why the probability rises from 0.5% in the UK to around 40% in the Russian Federation and Ukraine."

Simon agreed that "Google Play is a safe bet, but that doesn't mean you can't be compromised a different way," citing a Chrome exploit that enabled attackers to gain control over a Nexus 4 and a Galaxy S4 after users clicked on a certain link.

Is anyone trying to protect us?

The original researchers at Cambridge University are focusing on what OS vendors and smartphone manufacturers can do to combat this threat.

Simon's PIN Skimmer research paper also suggests various countermeasures, but the most effective come with a cost to usability. For example, blocking access to various sensors during sensitive transactions would keep hackers out, as would randomising the placement of digits on the PIN pad - but doing this would also limit what you can do on your phone and make it inconvenient to use.

Simon said: "When you're typing a PIN you don't really need to have access to anything, but it's a big decision for [manufacturers] to say 'we're going to block everything.' People might start complaining if they miss a call."

He later told us that Samsung suggested the proposed countermeasures to GP, for possible inclusion in the TEE standard, and that Qualcomm took the recommendations onboard.

What about biometrics?

Could developments like Apple's Touch ID be the answer? Rogers thinks it could. He said: "It's a really good way to bring security to the masses. It's convenient, it's easy to use and it fits within the user's normal processes."

While biometrics have some vulnerabilities, the big advantage is that they allow convenient two-stage security.

Rogers said: "A PIN can be tricked out of someone, but you can't trick a fingerprint out of them. If you marry the two, so that now you need two credentials to gain access, I would rate that security as pretty high."

So biometrics (found in the latest flagships from Apple, Samsung, HTC, and a growing number of others) are a positive step towards security. But it remains to be seen if they are the answer or if multi-factor authentication is a step too far for people who use their smartphones every day.

In 2014, Apple did reveal that 49% of people used a passcode before Touch ID, but since it was rolled out, 83% of iPhone owners now use Touch ID or a passcode. It seems that making security easier is a definite encouragement for users.

Ultimately, the only option may be to sacrifice some convenience for peace of mind. As Simon said: "Anything you can do to make things harder for the bad guys is always a good thing."