Ron Gilbert on recapturing point-and-click's charm with Thimbleweed Park

Follow the charm

‘Charm’ is an elusive quality. What might seem quirky or off-beat in one context can so often slip into the realms of superficial cute-ness.

It can be tempting to try to make characters light-hearted and whimsical, but try too hard and it can feel as though those characters are designed for children, rather than having that cross-generational appeal that true charm guarantees.

LucasArts’ adventure games of the 90s are the good kind of charming. Monkey Island remains one of the funniest games ever made, and the likes of Day of the Tentacle, Maniac Mansion and Grim Fandango remain infinitely playable despite their now-dated mechanics and graphical style.

That these games were good can be put down to a combination of good writing and excellent puzzles; but their charm is much harder to quantify.

Exploring the park

It’s almost reassuring, then, that Ron Gilbert, a pioneer of the genre and the man responsible for such games as The Secret of Monkey Island and Maniac Mansion: Day of the Tentacle is returning to the genre’s roots, rather than trying to recapture the same charm with a more modern game.

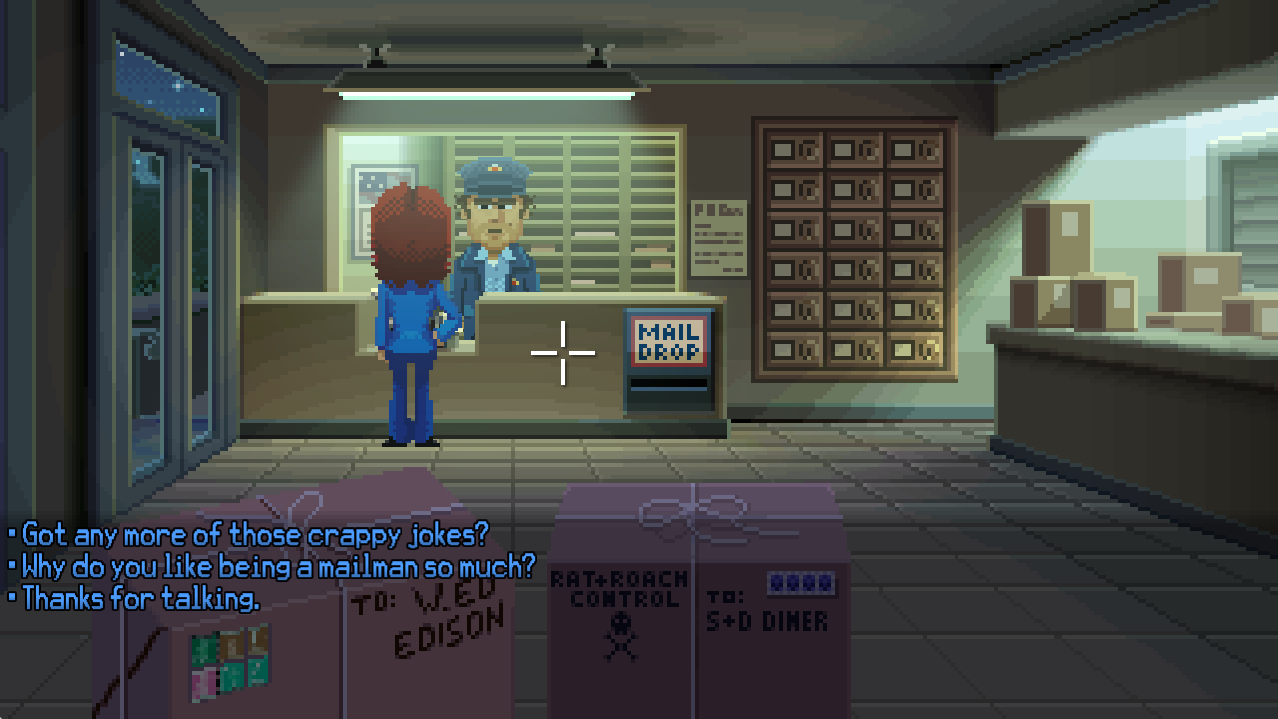

His latest game, Thimbleweed Park, follows two detectives as they attempt to solve a murder by exploring a Twin Peak’s-esque town, and utilises a pixel-based 2D art style and the same point-and-click interface that will be familiar to anyone who’s played a classic LucasFilm adventure game.

Left-clicking within the environment causes your active character to move, and you can interact with the environment by choosing from a selection of nine verbs, including such classics as ‘use’, ‘look’ and ‘talk’.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

“We want to build a game that’s how you remember those old games being.”

Ron Gilbert

So far, so 90s, but the real pleasure in Thimbleweed’s interface is how it streamlines this process. Characters will run if you double-click in the environment, or automatically walk through a door if you choose to open it.

Gilbert explains: “When you open a door, 99% of the time you’re going to walk through it … we want to build a game that’s how you remember those old games being, you remember that old stuff happening but it wasn’t. Walking through doors in Monkey Island was incredibly frustrating, because everything was just ‘open door’ and ‘use door’ and ‘walk through door’, and it was all this laborious clicking to get through stuff.”

The result is that the game’s combination of pixel art and point-and-click interface appear as you remember them, but in reality they function with a modern elegance.

These contemporary design touches mean the game doesn’t feel the need to include a hint system like the recent Monkey Island remasters. “Being about to design something from scratch, with an understanding that we have this slightly more modern or older audience with kids and families, has just caused us to file all the rough edges off of the puzzle-solving,” Gilbert says.

But don’t confuse filing off “all the rough edges” with “making the game easy”. Clearer objectives and characters that repeat key plot details are common tactics employed throughout the course of the segments of the game we’ve played, and this allows the puzzles to remain hard without becoming frustrating.

There’s even a harder difficulty mode included with the game that adds extra stages to the puzzle-solving for those who want a more involved experience.

A laid-back beginning

Although we were assured that harder puzzles are present in the game, the game’s early section that we played was a relaxing affair.

The demo opens with our two detectives, Angela Ray and Antonio Reyes, standing over a decomposing body (or ‘pixelating’ as the characters refer to it). They head into town in search of clues, and, after a brief interlude spent discussing the merits of adventure games with a couple of life-sized pigeons, start to become acquainted with the town’s wide cast of characters.

Before long we’re delving into the family back story of one of the Thimbleweed Park’s residents, playing through a flashback segment as a young girl who dreams of becoming a video game designer and escaping the town.

Every character we encounter feels like they have a similar depth to their back story, resulting in an environment that’s populated with characters rather than movie extras or cardboard cut-outs.

We only meet them for a moment, but the owners of the town’s diner appear especially interesting. “If you talk to them you realise there’s something weird going on in this diner with these two people,” Gilbert teases. “You start to piece together what their whole story is and why they’re in the town.”

A videogamey video game

The language of video games is baked into the soul of Thimbleweed park. Whether it's that video game designer subplot, or referring to a decomposing corpse, the game is proud of what it is – a traditional video game.

But as much as it’s a celebration of the genre, this meta-humor is ultimately present because Gilbert finds it funny. “As a vehicle for humor, I’ve always liked fourth-walling,” he says. “My favorite comedy movie of all time is Blazing Saddles. That’s a movie that starts out very normally, but ... then the end of the movie just comes off the rails. I just love that the movie does that.”

“I think the point-and-click genre is like book or film. There’s an infinite number of stories that you can tell.”

Ron Gilbert

Thimbleweed Park is charming and well written, and we’ve thoroughly enjoyed the time we’ve spent with it so far. Although the humor is often gently amusing rather than laugh-out-loud funny, this feels in keeping with the sedate pace of the whole experience.

If you’ve loved Ron Gilbert’s work in the past then Thimbleweed Park is an easy game to recommend based on the time we’ve spent with it – and from the sounds of things, Gilbert is nowhere near done with the genre.

“I think the point-and-click genre is like book or film,” he says. “There’s an infinite number of stories that you can tell ... and I think the point-and-click is just a vehicle for storytelling.”

“My dream is that Thimbleweed Park does very well, and I spend the rest of my life making a million units of point-and-click games.”

And we can’t help but dream along with him.

- If you're looking to get your PC fix, check out our guide to the best PC games.

Jon Porter is the ex-Home Technology Writer for TechRadar. He has also previously written for Practical Photoshop, Trusted Reviews, Inside Higher Ed, Al Bawaba, Gizmodo UK, Genetic Literacy Project, Via Satellite, Real Homes and Plant Services Magazine, and you can now find him writing for The Verge.