If you'd rather simply understand what you can see on clear nights, or fly a virtual spaceship between the planets, there's no shortage of excellent free software that can help you, much of which is also open source.

Stellarium is a fully featured virtual planetarium that will tell you exactly what you can see in the night sky. Turn off the atmosphere to get a better view of space by pressing [A]. You might also want to turn on the equatorial grid by pressing [E] so you can judge where you are in the sky more easily.

The best thing about Stellarium is that you're not limited to observing from Earth. Press [F6] select 'Moon' and you'll find yourself on the lunar surface. You can even speed up time by hovering the cursor over the location bar at the bottom of the screen.

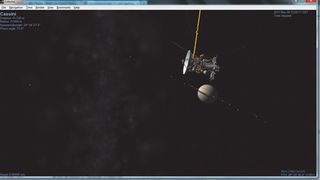

Celestia is an application that lets you climb into a virtual spaceship and travel between planets to see some far-out sights. It's more than a simple virtual planetarium; it's a real time space simulation that uses real data to plot the location of objects in our solar system and well beyond.

It's best to start with a demo, which you can enter by pressing [D], but Celestia also lets you fly around under your own control. Point your virtual spaceship in the direction you want to travel by dragging your cursor, then press [A] to accelerate. Your speed is displayed at the bottom left of the screen. To decelerate, press [Z]. To jump to a specific location, click 'Navigation | Go to Object' and enter its name. For example, to go to the Cassini probe, type Cassini and press [Enter].

Be aware, though, that Celestia can cause you to waste several hours doing things like flying through Saturn's rings, or making contact with space probes.

Worldwide Telescope

Microsoft Research's Worldwide Telescope is an even more impressive piece of software. It gives you access to the images from a collection of telescopes and sky studies, combined to provide a seamless view of the known universe - but there's a lot more to it than just amazing visuals.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

"Worldwide Telescope brings to life a dream that many of us in Microsoft Research have pursued for years, and we are proud to release this as a free service to anyone who wants to explore the universe," says Curtis Wong, Manager of Microsoft's Next Media Research Group.

"There's really nothing else that allows you to so fluidly put together your own view of the night sky and different objects and then share it in a seamless way," adds Jonathan Fay, a developer with the group.

The Worldwide Telescope has also been described as a space for storytelling, but what does it let you to do? For starters, you can add your own imagery to the default database. If you're already a keen amateur astronomer, this means you can create your own views of the sky, rather than relying on others to do it for you.

The Communities feature lets you make a global group of like-minded individuals to help you in your research. The hope is that teachers will also use Worldwide Telescope to make lesson plans that pupils can add to.

The default installation contains a catalogue of guided tours, and because the Worldwide Telescope is a collaborative venture, there are plenty to download too.

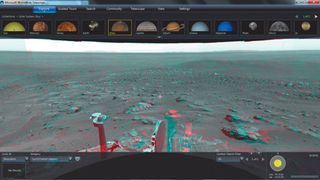

When mission controllers are driving a robot on another planet, like the Spirit and Opportunity rovers on Mars, they don't only have to use simple 2D television pictures and other readings to find their way around. It makes sense to also see depth, and Worldwide Telescope gives you a sense of how that must feel if you have a pair of 3D glasses to hand.

After downloading and installing the software, click 'Explore', then 'Solar System (sky)'. Click 'Mars', then select 'Panorama' from the menu at the bottom of the screen. The default image is a picture of the Apollo 12 landing site. Select an entry labelled 'stereo' from the Imagery menu and put on your 3D glasses.

The Spirit and Opportunity rovers have stereo vision, and the difference it makes to their images is breathtaking.

No satellite needed

If astronomy isn't your thing, there are other projects out there, including the Old Weather project. Climatologists are trying to predict future weather trends by looking at records going back to the 18th century. Are current fluctuations in climate unique, or have similar changes happened before?

Luckily, log books are available from ships belonging to the English East India Company. These stretch back to the 1780s and contain measurements of tides and weather, but they aren't the only resources we have.

When Darwin made his historic voyage on HMS Beagle between 1831 and 1836, the voyage was part of the South American Survey. Darwin was essentially a passenger, on board partly because Captain Fitzroy feared madness if he had no one of his intellectual status to talk to.

Data from this and similar voyages is also available, but the scientists trying to map historical weather have a serious problem. There are 250,000 ships' logbooks in the UK alone, and more exist in the USA, South America and Asia.

Clive Wilkinson of the Old Weather Project estimates that they contain billions of observations. The problem is, computers can't read the copperplate handwriting used to log them. This is where the public comes in - the text needs to be read and entered into a database. Once this is done, the climatologists plan to publish the data so people can make their own analyses.

This is very exciting; there's every chance that a non-scientist might make an important discovery about our climate. We live in an unprecedented time of technological progress, but it's also a time of data overload.

Because of this, scientific discovery is no longer the preserve of professionals. They need our help, which means that anyone could discover something amazing. In that sense, we're all potential explorers, boldly going where no one has gone before.

The universe is vast and mostly unmapped. There are still plenty of Voorwerps left to discover on Earth and out in space, each potentially stranger than the last. All we need is access to a PC.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

First published in PC Plus Issue 310. Read PC Plus on PC, Mac and iPad

Liked this? Then check out How to decode shortwave data streams

Sign up for TechRadar's free Week in Tech newsletter

Get the hottest tech stories of the week, plus the most popular reviews delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up at http://www.techradar.com/register