Foxy music: a history of the MP3

How the MP3 file format changed music forever

1999 was year zero for the music business. Napster launched and nothing would be the same again.

By the end of the first week, Napster had 15,000 users. By February 2001, its millions of users would be sharing 2.79 billion songs per month.

Every single one of them was an MP3. Had the record companies embraced digital music and offered rival, superior services using a rival music format, MP3 might not have prospered. But they didn't, and it did.

"The success of MP3 is due to its success as the format of choice on the internet," Harald Popp says, accepting that its bad reputation - for many years MP3 was seen by the media and much of the record industry as a pirate's format - may have made record companies wary of embracing it.

"As many people - knowingly or otherwise - violated the copyrights of the music industry by distributing songs coded as MP3, [it] understandably got quite a bad reputation among record labels in the early days of the internet."

But the record labels' enemy wasn't MP3. It was the internet. "The real challenge for the industry wasn't so much the MP3 format - there have been other formats as well - but the advent of the internet as a cheap and reliable channel for everybody to exchange digital data around the globe," Popp says.

"For a business that was (and is) selling unprotected digital audio data on physical media - CDs - to consumers, such a new channel was understandably seen as a severe challenge."

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

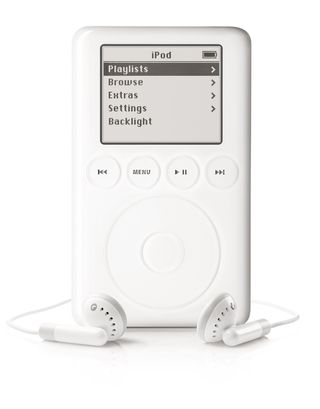

While record companies remained wary, the tech industry embraced MP3 with both arms. On 23 October 2001, Steve Jobs unveiled a way to put "1,000 songs in your pocket". It was called the iPod. You may have heard of it.

iPods, iTunes and the future of MP3

MP3 isn't the only format the iPod plays - and of course iTunes uses a different format, Protected AAC, for its downloads - but it's the most important one.

Ironically, legal music services probably helped promote MP3 over their chosen format, copy protected Windows Media: MSN Music shut its doors in 2006, killing music bought legally by its customers, and Virgin Digital did likewise a year later.

Other services, such as those operated by Wal-Mart and Yahoo!, followed suit in 2008. The message these closures sent to consumers was pretty clear: protected Windows Media was not a very safe buy. The fact iPods don't play protected Windows Media didn't help, either.

SYMBIOSIS: If the iPod hadn't supported MP3, it may never have been the success it is today - but MP3 might not be as popular, either

So where are we now? Despite competition from the likes of Ogg Vorbis, an open source MP3 rival, MP3 remains the format of choice for free audio, legal and otherwise, online.

It's the most widely supported audio format, with everything from mobile phones to car stereos and Blu-Ray players using MP3 compatibility as a major selling point.

It's the choice of most legal music services - Amazon, Play.com, 7Digital, EMusic, Sky Songs and so on - although Apple, the US's largest music retailer, prefers AAC. Not that Fraunhofer minds about that. "We also developed, in conjunction with companies like Dolby and Sony, another ISO format for audio: MPEG AAC," Popp says, pointing out that in addition to iTunes AAC is used in various flavours in mobile devices, radio receivers and commercial audioconferencing systems.

As for MP3? As you'd expect from scientists and engineers, Fraunhofer can't resist fiddling with it. "Together with Thomson [Fraunhofer's patent partner, Thomson Multimedia] we are developing and licensing a number of compatible MP3 extensions, like high definition MP3 (mp3HD) to preserve studio quality, a 3D representation of MP3 via stereo headphones (mp3D), or stereo-compatible multi-channel MP3 (mp3surround)."

These aren't replacements for MP3, though: they're optional upgrades, and they'll still work on systems that support MP3 but not mp3HD, mp3D or mp3surround.

As Popp points out, the reason MP3 is so popular boils down to one very simple, but very important, feature. "Any MP3 file plays on any audio player." Messing with that would be madness.

Writer, broadcaster, musician and kitchen gadget obsessive Carrie Marshall has been writing about tech since 1998, contributing sage advice and odd opinions to all kinds of magazines and websites as well as writing more than a dozen books. Her memoir, Carrie Kills A Man, is on sale now and her next book, about pop music, is out in 2025. She is the singer in Glaswegian rock band Unquiet Mind.